“Like my mother before me, and her mother before her, I have loved my share of men who are not named Joseph.”

Like my mother before me, and her mother before her, I have loved my share of men who are not named Joseph. Unlike them, I have not married a Joseph, yet. But when I met mine, the Joseph with hair grown split-end shaggy over his eyes, the rumpled shirt, the shoulders that hunched over mine like a shield, the feeling was that of a clasp clicking shut in my sternum. Yes, the voice that issues from that mass of blood and ventricles said, this will be what entraps you.

My Joseph is sweet. He is kind. He likes Cheetos dipped in chili, and well-worn polo shirts. He is improbably handsome. He swallows his words while he speaks, talks with fluttering hands. When his words bruise me, when he sees it, he is sorry, and he tries to heal the wound.

My grandmother’s Joseph, my grandfather, was a cheater—I never met him; I’ve only seen him in a few posed, unnatural photos. I imagine him suave, his voice as smooth as fine sand, gilded with mica. Which is to say: I imagine him slipping through my fingers.

My mother’s Joseph, my father, was an alcoholic: glum, thoughtless, addicted to pornography. She was not without her faults; she, after all, left him, in the end, just a few months after I was born—for another man, and then another, and then another and then.

My grandmother’s father predated the pattern. His name was Will. She will not talk about him, only about her ex-husband. “My Joseph was sly,” she will say. “Like a fox.”

She will toast him, as if still impressed after all these years. “Shell,” she told me once. “There are far worse things than a man like a fox.”

“Like what?” I asked. I was very young.

“A man like a bear,” she said.

![]()

My name is Michele, and everyone else calls me that. I can feel myself turning into my mother, and this scares me, but I can feel myself turning into my grandmother, too. I don’t know which option scares me more. I will not be controlled, until I will, and then I will be devastated. I will not leave in a reckless flurry, until I will, and then I will be lost forever.

“You hold on too tightly to your history”: a thing that no one has ever yet had the occasion to say to me, but I know that it is coming for me, if anyone watches me long enough, pays attention close enough, to notice. What I know about myself already is that I don’t hold on to anything else.

I met my Joseph at a party. Everyone was playing pool, and nobody was following the rules. The music was loud. A boy named Jameson with hazel eyes and wet lips was taking the pool balls one by one as he walked by the table when no one else was looking, his pockets bulging with weight. I had walked into the party with a crush on him, but the way he looked, his belt straining to hold up his cargo pants, made me think of a little boy. I was considering this when my Joseph came up behind me, his slim fingers tickling the back of my neck.

“Oh,” when I turned, he said, “I’m so sorry; I thought you were somebody else.”

“I’m not,” I said. I don’t remember whether I felt the portent of fate like a burden on my shoulders, or a clarity in my eyes, mud wiped out by a divine palm. I remember him asking if I wanted to go outside, which I did.

“I thought you were,” he said, when we stepped outside the glass back door, into a velvet night that thrummed with crickets. The party music was dimmed to a low hum, a rhythmic tapping, nearly drowned out. A strip of yard stretched between the back of the house and a battered cornfield. Above that, the infinite stars.

“Who?”

He grinned in a self-conscious, nodding way. His chin was strong, his teeth big. “It doesn’t matter.”

The grass was long, overgrown. Dew skated against our ankles and a gnat lit on the back of my hand, traced the line of my vein to my wrist until I smeared it away.

“You want to walk around front?”

“What’s up there? I haven’t been here before.”

He shrugged. “More houses. A cul-de-sac.”

“Cul-de-sacs are sort of magical, don’t you think?”

“I guess,” he says. “I mostly remember playing kickball in them.”

“Kickball is less magical.”

He looked at me. His eyes were searing blue in the moonlight. “I guess that’s fair,” he said. Just before he smiled, and without thinking it through at all, I leaned forward and grabbed a kiss from his wind-chilled lips.

“Okay,” he said. “Fine. They’re magical.”

I smiled against his chin. “That isn’t what I meant,” I said, and he kissed me again. His breath tasted like a mix between Froot Loops and the way a live animal’s fur smells. His hands scooped around the back of my head, slid up through my hair.

We didn’t go back to the party. A week later, we were officially dating. A couple of people liked it on Facebook, but not too many, since they hadn’t known us together for very long. I guess the speed of it made them apathetic, or uneasy. Me too, but I would be uneasy anyway.

![]()

My mother did not leave because of years of abuse, or even years of casual, graceful infidelity. My mother left because she wanted to.

“Oh,” she will say to me, even now, while she arranges her blunt-cut bangs to hang over her eyes, so that she always looks like she is peeking upward, “darling, you just wouldn’t understand.”

She has been affected like this all my life, and it makes me wonder. I imagine her as a girl at six, playing kickball in cul-de-sacs, her turn up at the plate, swinging her leg back with a haughty look, even the dirt on her knees perfectly designed.

I wonder: did my father Joseph ever feel like he knew her? Did he ever swipe the hair out of the eyes and see her face, bare-boned and astonishing, vulnerable and warm? And did he feel like he was holding something small but furious in his meaty palms, something that stayed still only ever long enough to trick them into opening? Something that, if ever trapped, would beat its whole self against his hands, hurling itself at the chinks of light between his fingers?

If my grandfather Joseph held my grandmother dangling from a string, then my father Joseph hardly ever stood a chance in tying anything around any part of my mother’s body. No bracelet on her wrist, no ring around her finger. Sometimes I miss him; other times, I think it doesn’t matter. I love my mother, and I have no interest in anyone who could stand between us. None of her other boyfriends quite could. She would let them take her out for romantic evenings, dinners with candles, flowers in her hair, but she was always home in time to tuck me in, to kiss my forehead with cool, dry lips, to smile faintly down at me while she turned out my bedroom light.

![]()

Soon after we met, my Joseph and I were sleeping in my room every night. He didn’t mind the creaking pipes, the heat-sodden flannel sheets, my weird taste in music. This is what I want, I thought, watching him sleep, tracing his face carefully enough not to wake him. His lips, curled up in a hint of a smile. The vein under his chin pulsed in time, kissing the pad of my thumb again and again. He is so pale, his skin so light and thin that I imagine I can almost see the blood coursing underneath it.

I think blood is interesting, scientifically, academically. The idea of family members sharing blood, and what are the parts of me that are irrevocably part of me—and this is one of the reasons why around that time, when I met him and his name was breathing down my neck, I started thinking about opening myself up to check on my own insides. I used to be a lifeguard, and every morning, we would test the water with little paper strips that changed color depending on chemical balances. I guess I wanted to know what imbalances I had inherited, and how to neutralize them.

I had switched my major to biology earlier this year, and it’s true that I loved the action of dissecting. But when it came to the inevitable option of myself as subject, the idea didn’t grab me the way it might have. Wrists were too easy, and I thought that maybe people would get the wrong idea. I didn’t want to slash myself to ribbons, didn’t want to devoid myself of consciousness. I didn’t want to hurt anyone. I just wanted to understand.

![]()

My Joseph was late to meet me at school. After I got sick of breathing gray film, of pressing the backs of my hands against the back of my neck for warmth, I scanned the flyers in the student center for events happening that week, that day, right then. I found a pop-medical seminar about the modern use of bloodletting in a hall across campus. I’d be half an hour late, but the lecture was two hours long. I collected my things, not telling Joseph where to find me.

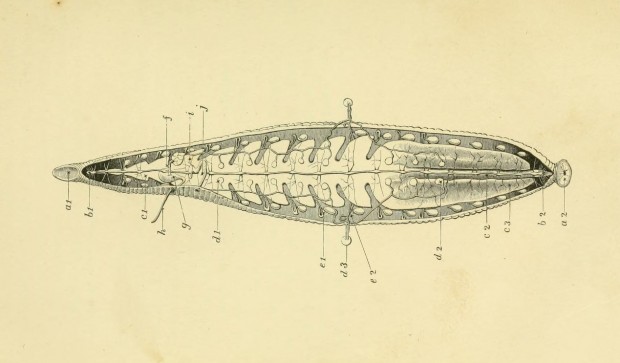

The lecturer was a woman with spindly limbs and hands that darted like waterbugs in the air around her. Her voice had the cadence and timbre of a zipper jerking up and down. I learned that we used to believe that our arteries were made of air. I loved that. Imagine if instead of carrying the wet rush of history as it runs in circles inside you—imagine instead carrying oxygen, people veritably floating, their bones wrapped round with breaths, the heartbeat run on gasps. I didn’t realize that I was listening rapt until I noticed myself leaning forward in the left-handed desk, its ledge digging in under my ribs.

While the lecturer talked, her hands alight and veritably sparking, a picture on the slide clicked over, from a list of medical terms to a close-up picture of a leech, attached to a forearm with its circular mouth. A slick, thin muscle writhed in my intestine. I gagged and clapped my hand over my mouth, imagining a ring of teeth squirming in my blood, latching on my pulsing heart, sucking me clean. I left, sneaking out the same back door that I’d slipped in, leaning against the cold hallway wall tile first to catch my breath, my skin clammy and grey in the sudden fluorescent light.

While I shambled back to the student center, I was certain that it would be empty, that he would be gone and he would never pick up his phone again. Gone for good, I kept repeating in my head, the words in a three-part rhythm with my slow steps, sing-song and definite, like a mantra or a spell.

When I got to the student center, he was there, reading a book I had told him I loved, wearing the glasses that he almost never wore. I walked right up to him to make sure that he wasn’t a mirage; I touched his hair. He finished reading the sentence, then looked up at me, his eyes green in the fluorescent light. I smoothed his eyebrow, knocking his glasses askew, and disintegrated into tears. And he held me. I shook so hard I thought my bones would come apart, and he jumped up, even without knowing why, and he held me pressed against him, hard enough to keep my body together.

I do worry about patterns. My grandmother was fully wronged. My mother was hurt, and did wrong in response. What, then, am I? Is my lineage a line or a spiral? You see my problem: I have been given the first two numbers in a pattern, and I am the third. How I choose will define the pattern itself.

![]()

My mother calls and warns me not to worry.

“About what?” I ask. I am distracted, washing the dishes. “Well, she says, hesitation hinging her voice from matter-of-fact to unsure. I turn off the sink, slide down the wall and sit on the floor. My hand pressing a scatter of crumbs against the floor.

“Mom?” I say.

“Oh, sweetie, don’t sound so concerned. I’m fine.”

“What happened?”

“I just tripped. I tripped on the sidewalk outside work, and I fell; I have a sprained ankle and a bit of a shiner.”

“Oh,” I say, breathing again.

“I’m fine, I promise, sweetheart, but I’m helping pack up your grandmother’s house tomorrow, and I’m wondering whether you might be able to help me—I can drive there on my own, and she isn’t taking much to the new facility, but it might be hard to lift some of the things.”

“Sure,” I say, rearranging my week in my head. My Joseph steps out of the bathroom, wrapped in a towel. He sees me sitting on the floor, my phone tucked between my ear and shoulder, and he moves toward me. I wave him away, and he goes into my room to wait for me.

The next morning we rent a car together, and our couplehood feels more official than it ever has before: here we are, trapped in an enclosed space together. Here I am, trusting where he takes me. That said, we’re not ready for grand meetings of family, yet—not that he didn’t offer; I just didn’t accept. He will visit his family in Pennsylvania while I help my mother. Happy coincidence; they are only two hours apart.

![]()

He drops me off in front of a house that’s a block away from my mother’s—ludicrous, I know, but I’m just not ready for any kind of introductions: hand-shaking, name-exchanging. He kisses me goodbye, his stubble a palm of sand across my cheek.

I trudge up the driveway, crunching a thin film of ice under my boots.My blood thickens under my skin, and slows, my thoughts viscous, my senses dulled. A lone bird chirps, sweet and shrill, from a knothole far above, and the sound pierces through the heart of the slumbering town.

I ring the doorbell, and hear her thin cry, “Coming!” from the recesses of the house a long moment before the door swings open. My mother leans on a sliver of a cane, dressed in sweatpants and a crewneck hoodie, the likes of which I have rarely seen draped over her thin, angular frame.

Her body lends itself to well-tailored clothing with classical lines, a hint of smoked eye, and a pale-pink lip. Her hair, usually side parted and pulled back, hangs loose over her shoulders in my signature style—the same wavy black, with the same propensity for tangling. Regardless of the genes the Josephs wove into the mix, my grandmother’s looks have duplicated themselves almost exactly on my mother’s face, and then again on mine. The only differences are in the eyes—mine slant when they crinkle the most; my mother’s not at all. No matter her expression, I’ve never seen them change their shape from orb-round, like marbles.

“Honey, you didn’t have to walk all the way up from the bus stop,” she says. “Why didn’t you tell me when you were coming in?”

“I wanted to,” I say, crossing my fingers behind my back. “It was nice to see the town. It’s been a while.” She nods, a curt jab, then grabs me to her chest in a brisk hug. Her hands are cold across my back. She pulls away first.

“How was the trip? What time did you leave the city?”

“It was good. I read.”

“Good,” she says, “good,” nodding again. “Well, would you like anything before we leave? Are you staying the night; do you have things?”

“I have work in the morning,” I say. “I’ll probably take a late bus out.” Her smile slips; I look away.

“Of course, honey,” she says.

I drive us across town to my grandmother’s house. I barely learned to drive before moving to New York, and I’ve never owned a car. My mother presses her foot against the floor, wincing, whenever she wants me to brake.

“Do you want to drive?” I ask. “I can pull over.”

“No, no, sweetie,” she says. “I trust you.”

Once we get there, she opens the door before the car has even stopped moving and hops out, lithe as an acrobat, twirling her cane between her hands.

“Shouldn’t you be using that for walking?”

“It comes in waves,” she says. “The pain.”

![]()

When we get to the door, she goes in first and my grandmother hugs her tight and steps back only barely, bracing her hands against her daughter’s forearms, not letting go. She assesses my mother’s face, her loose waves of hair. She presses the back of her hand against my mother’s forehead. “You rest,” she says. “Shell,” she says, turning to me, smiling sweetly, with distance, “I have boxes upstairs for you to go through.”

My mother is cowed. She slinks toward the couch.

“how’s home” my Joseph asks, my phone buzzing abrupt in my pocket.

“okay,” I type back. “kinda weird.” The screen shows him typing, and then he stops. The backlit glow goes dim.

My grandmother leads me up the stairs. “I’m worried about your mother,” she says to the back of my head.

“I know,” I say. “I wish she would keep off her leg. She’s going to make it worse.”

“What was that?”

“Walking it off never fixes anything,” I say. “At best, the sprain heals badly.”

Behind me, I hear a sharp-edged breath, but when I turn around, nothing has happened. She looks up at me, her face a familiar arrangement of lines and tics, a time-lapse view in a well-lit mirror, and she ushers me upward, holding tightly onto the bannister that I haven’t touched since I was a child, just learning to walk.

“Here you go,” she says, leading me to three cardboard boxes, taped securely, one slit open. “You go through these. Pick out maybe an album’s worth to keep.”

“How many is that?”

“Say, a hundred,” she says.

“How will I know which ones you want?”

She rubs at the crease between her eyebrows. “Just pick the best pictures,” she says.

“What are we doing with the ones you don’t want?”

“Oh, we’ll put them in storage,” she says.

She walks stooped back to the stairs and edges down. I open the box and start pulling out envelopes of photos.

Downstairs, I hear snatches of their hushed conversation—my grandmother is reprimanding my mother. I hear the words “hypertension” and “sepsis” and I stop moving, but their voices go more hushed, and I do not dare creep down and risk them hearing me.

Most of them are from around the time my mother was a teenager. I recognize my grandmother’s Joseph from framed photos in the house—one on the nightstand, one in the hallway, one over the mantel, to the left of an apocalyptic Biblical scene that I’ve never asked about.

In the photos he is cutting birthday cake: he is wearing swim trunks: he is cradling my mother in his tawny arms; she is standing on tiptoes to kiss his cheek while he kneels next to her, her cheeks scrunched up, her eyes slits in her grinning face.

He is classically good-looking, with puckish arched eyebrows and a square jaw that houses glowing teeth. My grandmother turns her small, pointed face up at him, her hair cascading down behind her. She didn’t know, then, about the other lives he held stacked like Russian dolls inside him—it was a deathbed confession, made in a haze of medicine and a sudden impassioned fear of Hell.

She confirmed it after his passing. I have never known her face without the lines that the truth troweled in. I have never known her eyes without cloaks of suspicion poised over them, ready to fall, her hands not ready to clench into a fist, to pull a cord and loose a veil for her to duck behind.

I have never asked whether or not he was a good father. Now, I begin my own side collection of photos to squirrel away with me and keep. I like the ones where he is holding my mother, smiling sidelong at her while she stares unflinchingly into the camera. He adores her. It is plainly visible.

I like the ones in which my mother or grandmother look the most like me, or when they’re talking to each other in the background, another subject grinning in the center of the frame. I like the ones where my grandfather Joseph is staring directly into the camera. I imagine that I can see the guilt etched into his careworn face, that the secret was taking a toll on him, that he didn’t like lying. That he wasn’t trying to destroy his family, but to protect it. I see one, only one, that features my father Joseph, a morose presence in a stiff event photo, everyone in formal wear under a white-hot sun, arranged like a high school class on a lawn of yellow grass.

The pictures aren’t sorted by year or even by decade—still, it is a surprise when I come across one that includes me. I am in the background, my grandmother kneeling next to me, reaching out to my leg, a long black sluglike body attached to it. I am wailing, my face bright red. In the foreground, my mother smiles brightly, unaware of the drama that unfolds behind her. She holds onto an elbow that I assume is my father’s, his face and half his torso cut out of the frame. I close my eyes, trying to remember that day, the oval mouth working against my knobby child’s leg, the slithering body sliding on my skin, the jaws, the way they must have gripped. I can’t remember it at all.

It isn’t until I hear my mother sobbing that I place the photos gently on the ground. When I sneak down the stairs and peek around the corner, I see my grandmother sitting next to my mother’s slumped form, the older woman’s arm around her daughter’s humped shoulders, stroking tangles out of her long black hair.

On the table between them, there is a black-and-white photo: a fetal shape caught in a triangle of TV static. I gasp and they jolt.

“Michele,” my grandmother says in a tone like an axe, “Go back.” And I scurry off, cowardice coursing like acid in my blood, eating at my bones, leaching into my marrow like a lifelong curse.

![]()

On the way back home, she drives.

“When were you going to tell me?”

“I don’t want to have this conversation,” she says, her eyes on the road, her thumb tapping against the wheel. I lean my head against the window and speak against the pane, so my breath fogs the glass.

“Did you already do it?”

She eases the car into a sharp turn, slowing to a crawl. The headlights glaze against patches of black ice ahead.

“Yes,” she says.

I keep my mouth clamped shut for the rest of the ride, until we pull up alongside the curb and turn into the driveway.

“Are you okay?”

“Yes.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I ask. She has turned off the ignition, and we sit in the driveway. The sky hangs low over us, blurry with starlight, like a skein of air-pocked ice over a black lake.

“I didn’t want to discuss unrealistic options.” She exhales, and the cloud of her breath shimmers before it goes. “I can’t be a single mom, Shell. I’m not cut out for it.”

“You already are.”

“Yes, well,” she says. She jangles the keys in her palm, wraps her fingers around them, obscuring them from view. “I thought your father and I could make it work. By the time I–” she coughs delicately into her closed fist “—realized otherwise, it was too late.”

“Oh,” I say. “Right. Okay.”

“Oh, sweetheart,” she says, looking finally at me, her eyes swimming in feeling. “I don’t regret it; I never have. I love you more than I could ever have imagined. You must know that.”

She folds me in an embrace, her heartbeat erratic and fluttery against mine. Her hair smells clean, like slick ice or cold glass. I watch the window behind her, the steam of gray stone road, and across it, the black woods, outlined in slicked-over snow.

“I know I’ve made mistakes,” she says, and while my shoulders stiffen, I say, like I always do, “No, you haven’t.”

My Joseph picks up on the first ring. “Babe,” he says. “What time do you need to be back?”

“Soon,” I say. I can hear a whole carnival of laughing children in the background. I imagine them playing tag, snatching at each other’s shirts, throwing their heads back in glee. Their small pointed canines, their grabbing hands, their curly hair, all brown, soft and lustrous as piles of ribbon. I imagine one of them motoring by him on pudgy legs, one grabbing him around the shins. He is laughing, too.

“What? How about early tomorrow morning?” he asks. He is in a kitchen somewhere, I think. Blue tile flooded in yellow lamplight. Something is baking in the oven; something has simmered all day on the stove. The air is thick with mingling scent, stuffed loud with screams of laughter.

“Sure,” I say. “Tomorrow morning is fine.”

While she is taking a shower, I leave her a note. I sign it with love. The door creaks as I let myself out, the ice groans in a faint whine as I tread down the porch steps, out across the cracked macadam. The bus stop at the center of town is only a twenty minute walk away, and the bus will arrive in my city only an hour after that. I’ll be back home before the night has reached its darkest hours.

![]()

As soon as I step off the bus at Port Authority, I google a bait shop. Three pop up in my immediate vicinity, two still open. One clerk, a boy with a patchy crew cut and an earring as big around as my thumb, hears my request and shakes his head. The other, though, nods briskly and leads me to a tank in the back corner.

“Thirty?” she asks, incredulous. “We only have eight. Why would you need thirty?”

We settle on eight. I tell her that I already have the food, the tank, and the filters, at home. She doesn’t doubt me. She places the translucent plastic bag into a brown paper grocery bag

“So they don’t get stressed out by the journey, she says, smiling into the bag’s wide mouth. She rings me up.

When I get home, I don’t bother turning on the lights. Shadows cross over my feet as I step in, the handles of my grocery bag looped around my wrist. I reach in and pick the knot apart. When it comes open, water flows out of the plastic bag, drenching the paper bag, soaking into the mattress. I stir my fingers around until I feel a thin, thrashing body. I pull it out as gently as I can.

In the dark, I can’t see any of its features or markings—it is a slick blur that wriggles andslips like a gob of phlegm between my fingers. I place it against my arm, in the crook of my elbow. It squirms, but I hold its midsection pressed against my skin until I feel its jaws clamp: a jab that keeps throbbing. I clamp my lips between my teeth and hold my arm still and rigid. The leech rocks against my arm, twitching as it gulps. I reach into the sodden bag and pull out another one.

In the morning, my Joseph will come home to me, still lying here, and the eight of them still latched on me, still hungry. “Why?” he will ask. He will struggle to remain calm.

I will reach for him while my bloodline drains out. I will touch his cheek and I will pull him down to kiss his lips and I will say into his open mouth that I am trying.

“Trying what,” he will ask, and I will say, “To get better.”

*

Image courtesy Biodiversity Heritage Library