How do we talk about Tristano when every copy is different? The same way we talk about the world.

In most possible universes, you would not be reading this. A busy day at work could have kept you from the tweet that led you here, or you could be one of the billions of unfortunate people who have never heard of Blunderbuss Magazine. I could have been flattened by a bus before getting the chance to click the publish button, or a friend’s Facebook post might never have led me to the sale on the Verso Books website that persuaded me to order a half-priced copy of Nanni Balestrini’s Tristano, the weird little experiment in literary contingency that set this review in motion. The odds were set against things happening as they happened, but they happened.

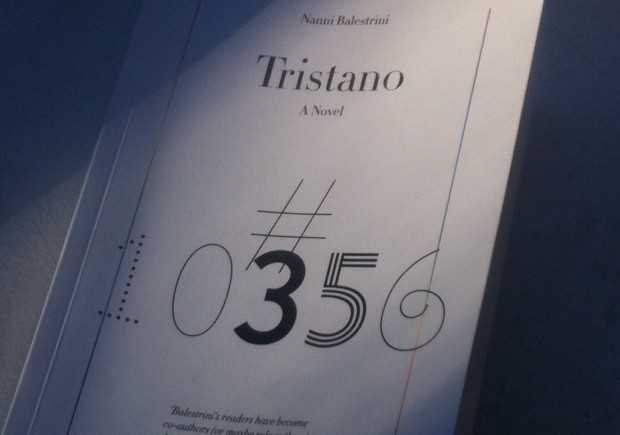

Chance is central to Tristano. Even in the alternate universes where I still bought a copy, odds are I would have wound up with a novel that was substantially different than the one I read. Back in 1966, Balestrini conceived of the book as a kind of game. He wrote 30 paragraphs for each of Tristano’s ten chapters, but in any one version of the book, a given chapter contains only 20 of these paragraphs, and they are arranged in random order. It was a scheme that digital publishing techniques only recently made feasible. According to the back cover, my copy—number 10,356—is “one of 109,027,350,432,000 possible variations of the same work of fiction.”

As you might expect, the result sometimes borders on nonsense, or, as Balestrini puts it in one of the book’s winking asides, it takes us “almost to the limits of intelligibility.” Nominally, Tristano is based on the legendary doomed romance of Tristan and Isolde, though its plot (at least in my version) is essentially unfollowable. The characters are all referred to only as “he,” “she,” or “C.”—a letter that is also used (I think) to represent any proper noun. None of these characters appreciably develop. Much of the time, I couldn’t even tell who was speaking. There are no punctuation marks other than periods. The book is well aware that it’s no pleasure to read. “When confusion starts,” it says in one passage, “agitation automatically follows.” Tristano did agitate me. It is, after all, billed as a “radical assault on the novel,” and I’m a guy who likes novels. The experience wasn’t fun, or moving, or riveting, but as I forced myself to slog through its juxtapositions and disjointed scenes, I started wondering if there was an idea embedded in the project’s architecture. Through its play with contingency, variation, and instability, Tristano forces us to talk about it like we talk about the world and about politics. It situates us in a specific viewpoint—different from but no less legitimate than anyone else’s—and then challenges us to seek out the common ground that makes discourse possible.

![]()

German composer Richard Wagner covered this mythological terrain a century before Balestrini, and his opera Tristan und Isolde was inspired in part by the work of philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer termed everything that we can perceive with our minds and our sense organs—all of the particularities of lived experience—as “phenomena.” Separate from but present in each phenomenon is the “noumenon,” an unknowable unified reality that grounds and connects everything.

It’s not hard to follow this line of thought into the pages of Tristano. Each version of the book is a phenomenon, a particular object we can point to, hold in our hands, conceive of in our minds. However, the totality of Tristano—the abstracted sum of its 100 trillion possible avatars—is so vast as to be incomprehensible. This incomprehensibility makes it a difficult novel to discuss. If you too were to decide to immerse yourself in its strangeness, then you and I will have read different books. Balestrini therefore denies us one of the most satisfying aspects of art: the shared encounter with a particular crafted experience. You and I might disagree vehemently about, say, “The Wolf of Wall Street,” but the thing that we’re arguing over is static. We are reacting differently to the same experience. This is why we go to the movies on dates—they give two people who might not know each other very well a common thing to talk about.

Tristano tinkers with that pleasure. It randomly assigns each of its readers a different but overlapping experience, and refuses to distinguish one text as authoritative. Passages that were key to orienting my experience of the book might be completely missing in your edition and vice versa. Rather than the coherent, distinct interpretation of the world offered by fixed pieces of art, we’re left with something varied and multiple, something more like the world itself. In neither Tristano nor life do we just have different opinions about a unified reality—that reality is actually different depending on the edition we read or the circumstances we’re born into.

In a way, Tristano stands as something like an adult leftist counterpoint to the lunch table libertarianism of the Choose Your Own Adventure series. CYOA foregrounds the individual’s choices. To enter the haunted forest, turn to page 12. To return home, turn to page 31. You make your own destiny. Did your face get bitten off by the Space Vampire? That shit is on you. So a ninja cyborg killed your whole family? It’s not the government’s job to pick winners. Our experiences in the War with the Evil Power Master will be different, but it’s because we made them different.

Similarly, you and I won’t read the same Tristano, but—and this is key—it’s not because we exercised our free will and chose our own fates. It’s because Verso mailed us different copies and locked us into our respective texts before we ever had a say in the matter. Our experiences were shaped by forces outside ourselves. You might not witness scene of domestic abuse I read in Chapter 3—maybe you’ll be spared the violence or encounter something even more heinous—but this discrepancy is not because of anything you or I did. It’s because fate stacked our decks differently. Individual choices are pushed to the background as an externally inflicted structure comes to the fore. To change our text we’d have to go to the root, back to the Verso warehouse or even to Balestrini’s algorithm.

![]()

The problem of how to talk about Tristano is a small-scale version of the problem of how to talk about our world and our politics. Without a fixed sacred text to refer to, to arbitrate what the book really says or what the world really is, we’re left to negotiate between realities that are effectively infinite. To look at the world as though my experience as a son of the white middle class is the universal yardstick (a mentality implicitly on display anytime a politician draws the boundaries of the “real America” or, more subtly, a college syllabus cordons off a special week for gender studies) is as obtuse as insisting that #10,356 is the “normal” version of Tristano.

Like our versions of Balestrini’s novel, our varying experiences in the world are to a tremendous extent determined by systems we did not devise. Within a mind-meltingly complex equation of economics, politics, race, gender, geography, and a million other variables, our individual lives can vary so greatly that mutual understanding may seem hopeless. But it doesn’t require a complete knowledge of some unified noumenon for us to be able to speak to and comprehend one another. If we look at the overlap of our texts and the commonalities of our experience, the traces of our collective reality start to come into focus. Global capitalism and the specter of ecological disaster have perhaps brought our stories into greater congruence than ever before. They threaten us regardless of who we are and what we look like, and it is our political responsibility to leverage these points of common concern and build a Left that is genuinely ecumenical.

Unfortunately, we can’t go back to 1966 and fiddle with Balestrini’s algorithm. We can’t give Tristano a compelling story and interesting characters, and we can’t tone down its cringeworthy on-the-nose moments of self-satisfied meta-ness. But the algorithm of politics is malleable. It can be reformulated so that the result is more equitable. Acquiring the necessary momentum, however, requires us to be as interested in commonalities as we are in differences. Maybe that’s not such a bad takeaway from a thoroughly unpleasant read.