“When Luis moved back it felt like time travel.”

I kept my distance from Luis as long as I could. We played chess, separated by the board and my coffee table. We argued about guns, about politics, but I wouldn’t sit next to him as we did. He told me stories about the places he’d been after he left Rifle and I’d refrain from physical contact, refrain from staring too long at him. This summer, he sent a series of postcards from Vegas, Disney World and Los Angeles. The last one said he was moving back to the Rocky Mountains. Back to the place we both grew up. He had been gone for five years. I have never left this town in all the 23 years that I’ve been alive, have never left the cradle of the Rocky Mountains, not even to see the cities scattered across the Front Range. His card read that he lost his job, needed to find home base again, a place to recoup. Blue ink that dipped and rose like valleys in a mountain range said, Rifle is cheap and quiet. It said I’ve also missed you, so there’s that.

![]()

The summer after we graduated high school, my father was let go from his job as a hand on one of the local farms. I started working the register at the general store to help out. Luis told me he would stay for the summer and after that, he would be gone. He wanted to be a famous photographer and could not do that by staying here.

I had this six-foot antique hookah sitting in my room and told Luis I needed his help to turn it into a lamp. I was always using ploys like this to get him to come over. He seemed enamored with me when I was around, but when he wasn’t near me I was always left wondering about just how he felt.

When I told him about the hookah, he laughed. I rubbed the soft bronze with my hands, my fingers traced the divots where the pentacles were carved into the metal, darkened from years of dirt. I never finished projects and he knew it. Sometimes you need to force things.

“If we make it a lamp, we could have three wishes,” he said.

But I couldn’t run the cord through the stem of the hookah, so instead of making a lamp, I filled it with water until it overflowed and cleaned out the insides. Luis decided to make tar tobacco with rose petal molasses and thick, sweet honey. This became our ritual. With a coal on top, we’d suck the sweet sugar smoke into our lungs, releasing the billows like tiny trains.

The day before he was going to leave, I bought a dozen bouquets and filled my basement bedroom with thick, peaty smells of lilacs and lavenders, roses and sweet alyssum, hung up garlands of gardenias around the garden level windows. My dad had been unemployed for a couple months at this point and I could hear his footsteps creeping above us, wary of whatever his teenage daughter was doing with a boy in her room. Luis sat on my bed, muddling together that tar tobacco in a bowl. I was being half-sarcastic about the lamp. Who had ever wished on a lightbulb and an electric cord?

He took a break from the rose petal honey mixture and scratched his beard, which had grown in thick over the spring.

“What would you want with three wishes, anyway?” I asked.

He picked up a spoon and fed the tobacco mess into the bowl, big as my fist, then placed the aluminum on top.

“Three is a magic number,” he said. “One is the beginning. Two is the struggle. Three is progress. Movement. That’s what I want.”

He poked holes into the aluminum. Then he lit the coal, placed it on top, replaced the cover that goes over the coal. His ritual. He sat down on the floor, sucking in air from the hookah hose.

I wanted growth, too. Or movement. For him, that meant travel. He wanted to leave Rifle, see the vast belly that the country had to offer him. My parents needed me, and besides I couldn’t think of anything else I would do. I didn’t know anything else. I sat next to him on the floor and pushed my fingers into the blue plush plumes of the carpet, trying to ground myself. I closed my eyes and my fingers and palms turned into roots and my hair began sprouting leaves. I didn’t want him to leave. My skin crackled into the grey ash of aspen bark when his voice broke my transformation.

“What would you want?”

I heaved my chest.

“I don’t know,” I said.

My father was growing more miserable each day and yet my mother would continue to make dinner every night like things would be okay. We did not discuss troubles out in the open but when I was alone with her, in hushed tones she would tell me that we were falling behind on the mortgage and that things were going to keep getting tighter if dad didn’t do something, and that I needed to keep working to help the family out. I needed to be here for them, she said. I thought of the general store, the moldy smell of the old building and the measly paycheck I was getting. But the owner, Jim, said he would increase my hours, so it seemed promising.

I leaned back into the pillows on the couch, throwing my hands behind my head to look relaxed. I could feel the warmth of Luis’s body close to mine and I did not want that to change. I didn’t want anything to change.

“I think I would want to freeze time,” I said.

He laughed in this way, a sort of half-giggle that overtook his chest. I did not think that freezing time was as farfetched as movement.

“The past is still a part of you,” he said. “But you can’t stop progress.”

I took his hand in mine, cradled the warmth of his fingers against my palm and placed it on my thigh. I let his hand rest there as we sat, staring at the garlands on the windows, the light casting shadows of flowers against us. It didn’t matter what we did, if he felt anything for me, as long as the moment could be remembered.

“What would your second wish be?” I asked. With our hands together, he leaned back onto the pillows and pulled me closer to him. Luis smiled softly and then let his eyes wander away from mine, towards the window.

That night we made love, his body heavy against mine, our skin moving together like beach sand. The tiny world we made around us.

The way a person sticks to you. You have to slough off the skin.

Afterwards we drank wine and took turns taking snapshots of each other in the mirrors on my closet doors with his expensive camera. The flash washed us out, darkening the reflections with bright stars in the middle of the photographs where we’d be standing, holding the camera. We looked like other-worldly angels or fairy creatures. Like each picture caught all the light inside of us. He’d ask me to pose, and we made it a game.

“Move your head this way,” he said, and then, “adjust your shoulder here.” I sprawled on my bed, childhood sheets and cutoff shorts, topless. He’d snap the photos and look at each shot on the LCD screen. He told me that half of performance was the show and I would try to make my eyes and lips look fierce, intimidating. I was always trying to be cool. I think he knew that but he liked me anyway.

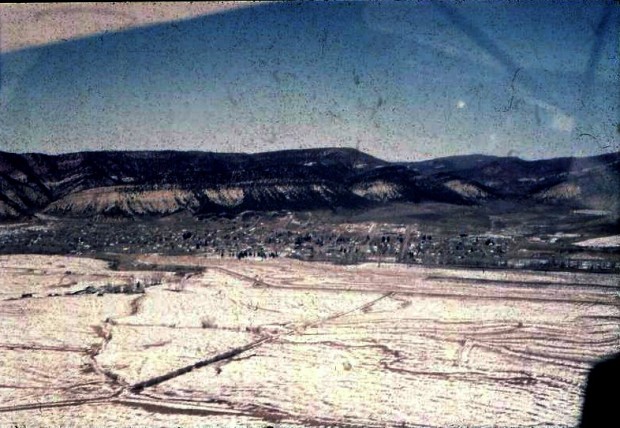

From the balcony of my parents’ home, we watched the sunrise over the Roan Plateau. He’d be leaving in a few hours, to New Mexico maybe, a place more wide and open than our cradled town. There are only a few moments I remember from these times. Short. Intense. The way memory works. A photograph stuck in a box somewhere and relived later.

![]()

The image frozen in my mind is like this: It’s the next morning. The air is cold and he’s standing in the spot in my doorway, slim shoulders against the metal jamb. My hands wrap around him, fingers on his spine. My arms inside his jacket. He kisses me with teeth, kisses me goodbye, I don’t know. Words inside every other kiss, he’s saying,come with me, come with me, come with me. But I can’t do that. He puts his hands in mine, pulling me forward and out the door. My parents will be awake soon. He says I have these real doe eyes, the way I look at him like a young Jean Harlow, my round face with eyes that have always looked up to the sky, up to him, like I’m praying. Then he bites my bottom lip and wraps his hands around my ribs, leans into my body like a daisy into sun. After that, he walks away.

The way this scene ends, I stare at him through the crack in my door, wind blowing through onto my face, drying out my eyes. I let us die in the spot in my doorway. I do not cry.

![]()

When Luis moved back, it felt like time travel. Like we were meeting for the second first time, like we’d somehow met in past lives that no longer existed.

It’d been five years. My parents had lost the house and were renting a place a couple streets away. My mother was working and my dad had slipped further into a kind of depression. After I found my own place to live there was no need to pretend everything was normal anymore. My father was free to drink, unjudged except by his wife, as if it wasn’t a problem at all. The owner of the general store had promoted me to manager and I was in charge of other people, had responsibilities, a sense of purpose in my life. There had been other men, too, but no one that felt important or permanent or serious.

When Luis moved back, he brought a girlfriend with him, from whatever town they’d been living in. There was no mention of this in his postcards, nowhere at all did he say—in fact, he didn’t even tell me until he was here, ran into me at the store when I was working. He said it at the last minute, My girlfriend, she’s waiting in the car—an afterthought that gave me desert guts. He would come over to my place to hang out but didn’t really mention her. Each awkward smile, my dry mouth every time his eyes flashed at me this certain way. Each time he left my place he’d say I gotta be back by 9 o’clock. The way my stomach burned, empty and hot.

I wanted to go to an art gallery one night. A friend at work was having a show. I wanted Luis to come with me. I wanted to keep my distance but didn’t want to go alone. I drove us up the road to Silt, a smaller town just east of us. The gallery was in a Homesteader’s cabin, about 100 years old. In my rusted ‘80s sports car, we pulled up the gravel drive and this tiny house stood underneath the umbrella of Chinese elms. Apricot, apple and plum trees surrounded the fieldstone building. The art itself wasn’t much. It was dark when we left.

When we parked at my apartment building, he hugged me goodbye in the car and hesitated a second before letting go. Almost two months to the day of his arrival back, after keeping my distance for so long, this was the moment he chose to stop moving. He froze, hugged for just a little too long. I leaned into him, quickly reaching for the door handle on his side and pushed him out of the door, out into the cold, leaning into the passenger seat. I tucked my chin a bit and raised my eyes up at him in that Jean Harlow way he liked so much.

“Get outta here,” I said. “You’re killing me, man.”

He smirked in this way where his face comes alive, the snap excitement of a new thing.

“You’re going to make me walk home?” he said, half-laughing. He wrapped his arms around his sides, rubbed the flannel shirt he was

wearing. “It’s so cold.”

My first wish, freezing time. I held my breath so long trying to decide what was the right thing to do that I started to see spots go in my vision. I heard him kick the gravel a bit, move his feet.

I said, “Ok.”

I said, “Get in, I’ll drive you home.”

The way his fingers felt against the fabric in between my legs, the way I rocked my hips gently against his hands as his mouth was against mine, teeth and tongue together. He was still shivering so I wrapped my hands around him, underneath his shirt. I wrapped my hands so far around him that I could feel the bumps in his spine, the warmest parts of him.

After that, Luis walked the half-mile home. I have to go, he’d say it over and over again, whispers in my mouth. Home to the place he lived with his girlfriend. I was sleepless that night, and for many nights after.

After the art gallery I was desperate to get him to come over. I became obsessed with his hands against my skin, the shape of his mouth, with things I could not have or possess or hold against my body. It was the same game. When he was around he seemed enamored, but when was gone less so. Was he thinking of me? Did he want me the same way? I would text or call and get no answer for hours, sometimes a day or two. It was as if he did not understand the urgency of the situation, of my need or of our need to be together in the same place.

He left for an assignment one week, and told me he’d come back a day early so we could spend the night together. I counted the minutes until his arrival and cooked peppered beef tips in local butter, pan fried summer squash fritters, baked a thick rhubarb strawberry pie for desert. Pretending, the way my mother did, that it wasn’t all going to end.

We drank cheap beer after beer together, hardly touched the squash or the pie. When it was dark, I grabbed a blanket big enough to wrap around us and took him out to my balcony. I had a downstairs neighbor but that was it. No cars were passing through. At midnight you hear the cicadas singing their sun song to the streetlights, the crickets, maybe an owl if you’re lucky. We laid in the blanket, our hot breath underneath it and looked up at the star sea above us shining down.

“It’s not like this in cities, you know.”

I laughed and pushed against him, our shoulders touching.

“I know, silly.” I said. “I know there’s a world outside of this town.”

“You might know,” he said, “but you’ve never seen it.”

A hint of jealousy thronged my body. I’d never be as traveled as his girlfriend probably was. I rolled my head against him, pushed my face hard against the fabric of his clothes. He was right. I’d been here so long I was almost afraid to leave.

Underneath the blanket, I pushed myself on top of him, our hips touching. I could feel his hands form a gentle circle around my neck as I tugged his pants off, and then mine, moving my panties aside, hoping that nothing but the night birds could see us.

When his girlfriend found out about me, she left back to wherever it was they met. Somewhere in the heat of Albuquerque. I was singing to heartbreak songs on my way to work one day when I realized she might very well be singing the same song to herself in her own car, on the very same highway, thinking about me.

After the breakup, he avoided me for weeks. My suddenly free schedule consisted of getting drunk alone on hibiscus-infused vodka and rose water tea, and playing Cat Stevens over and over again on my laptop while I cried on my couch. I blamed myself and the distance was damning. Sometimes I’d just sit on the floor and use my coffee table as a prop for my head. Rolling into work the next day with braided unwashed hair and crumpled clothes, only to stare into space.

I didn’t understand why he wouldn’t reach out to me. Maybe he blamed himself. Maybe we had spent too much time together and the novelty had gone once his girlfriend left him. I tried to let go, to become unobsessed, but it would ring up inside of me again, it would ring and ring until I felt the whole of my skin would crack against the air. The way newness creates a longing for more of it, the need to constantly be seen, to constantly be wanted. I spent the better part of three weeks fantasizing about a life with him when I was without him. I could not determine whether life with him was worth a loss of stability, the fact he didn’t have a steady job, that he perused dollar stores in cities for peanut butter and loaves of bread just to survive. I saw what the instability did to my parents and didn’t know if I could take the risk on something like that.

It was after this that Luis came to me one night, knocking feverishly. I opened the door a crack, the chain still on.

“Come west with me,” he said. “I’m leaving.”

I hadn’t seen him in three weeks and he was here, telling me to come with him. He wanted to live in the sharp valley of Vegas where I imagine the air has that electric feeling when it storms and the lights make you dizzy. Where the city glows like glass in the sand.

“Don’t you want a bigger life?” he asked.

A bigger life. The wasteland air snap of a hot dust bowl. I wasn’t sure what to say so what I did was stare at him, stare past him, at the darkness of the sky around him.

I undid the chain and lead him inside, where I sat down at my dining room table. It was a plastic card table, inherited from my parents when I’d moved out. Cheap lawn furniture, two small cushioned chairs, one cradling me. To my back was an open window, breeze coming in. It was a cool night, but mild. Warm enough for the mosquitoes to bite.

He said, “Look, my lease is up.”

I lit a cigarette, and without making eye contact asked,

“Already?”

Before anything had a chance to cement, things were already changing. I didn’t get to have him when he was alone, here in Rifle. We had to run around clandestine the whole time. And now he was already leaving?

His car was already packed with everything he’d ever owned. A few posters and plastic cups, a record player, an air mattress.

He asked again, “Are you coming with me?”

After the weeks of him gone, after how much it hurt, I didn’t really know what to do. I looked beyond him again, out into the night, onto the only main road that passed through town. Across the street was a row of tiny homes, all neighbors I knew, people who held the place up with their feeble fingers, people who chose to stay during hard winters, during bad financial times, who had never known to choose anything different that the life they had now. Luis was someone who would stop choosing me. I could see that he was someone who needed to move often, who was possessed by novelty.

I couldn’t move. I didn’t know if I could love him all the way through, down to his fingertips, down through hardship and zero safety net. All the way through bad times, didn’t know if I could wander down dollar store aisles looking for food in a glittering city of noise. What did that mean? A bigger life?

I had prayed for him to come to home to Rifle and once he did, I stopped praying. I did not consider that I would have to start over. Why did it have to change, I wondered. To move beyond it made it too big. I did not consider how we could connect all these moments together to make a life. I did not consider that we could exist outside of the stories we held about each other, the way we existed only in these short moments over the past six years or so. So much of that time we spent apart, so much of the distance is what made me want him.

The way the past was still a part of us, it’s why we’re hanging on.

My head started to buzz hot, my cheeks, my limbs turned pink with the fear of truth-telling. Even at the last moments, the way we ended. I started explaining how I had to pay off some bills before I could move. How my parents still needed me, they’d need to find a replacement at the general store for me. I said I’d follow him out there after a few months, but it wasn’t the truth. The truth stayed inside, burning me up. I could not say no to something I had wanted for so long, which now became something I feared. Not outright. The buzzing inside me grew with every word, and then I swear it started bouncing across the room. I breathed in hard, sucking air through my teeth, letting it out slowly through my nose, trying to figure out how to still my heartbeat. Dry mouth, dry tongue, cheeks hot. His brows pushed together as I spoke each word, his mouth was tense, unmoving.

We only existed in the looks we give each other, across dinner tables, in art galleries, holding hands. I knew this now. I told him that I loved him, that he could go and I would follow.

Suddenly the buzzing was on the ceiling. Somehow it had leaked out of my head and was flying frantically around. It hit the lightbulbs with a little pink, pink, pink.

The way memory made me relive the way we fell in love over and over again. It’s just legend. The pink pink sound. My head buzzing above. Just said yes to say no later. I thought back to hanging gardenias on the windows, our Friday nights when we’d smoke rose molasses tobacco and make up wishes we’d want if we’d had a magic lamp. “Before you go,” I said. “Tell me about your third wish.”

I waited for him to say something, waited to see if he remembered. Couldn’t read if he knew I was lying this whole time or if he was just quiet until finally—

“Wasp,” he said.

What?

“Wasp,” he said. “Wasp!”

Luis ran into the living room as I looked up, and there it was, flying around, looking for any way out. I tore open the kitchen cabinets underneath the sink and grabbed a bottle of blue window cleaner, holding it like a gun. My eyes darted around the dining room and kitchen, waiting for the wasp to land. Luis peeked around the corner at me.

It’s really graceful, the way a wasp flies. They look like little fairies when the light reflects right, wings like gossamer, dainty legs. I’ve never been stung. I waited for it to land. Its legs touched the countertop and it stopped. Luis peeked around more, eyes wide like he’d never been stung before, either. I cocked the cleaner gun and shot—squirts of window cleaner coated the bug and it fell to the floor.

In a blue puddle, this dangerous little thing was rendered harmless. I got on my hands and knees and stared, as close as I could get, watching the wings struggle to beat in the liquid. Luis watched me watching the bug. It was having a seizure, curling up and uncurling until finally it stopped moving. Movement, and then nothing. Frozen in time. The way it allows you to dive in for a closer look, to examine all the details from a safe distance. Without fear of getting hurt. I stared for a few seconds longer and then grabbed a paper towel and cleaned it up. I kept glancing at the wasp body in the muddle of paper.

“Hey,” Luis said. “I really have to go.”

He grabbed me around the waist to hug me, my hand with wet paper against my chest. It bled through on both our shirts as our bodies came together.

It was at least eight hours to Vegas and he was set to meet an apartment manager there so he could find a place to live. He had a long night ahead of him. I said I know and kissed him in that movie star way, leaning against the metal of the doorjamb. The spot in my doorway, a holy spot. I watched him walk down the stairs as I closed the door, still clutching the wet ball of paper and the wasp.

*

Photo by Judy L. Crook.