Two things are certain about the new year: tradition will live, and people will die.

Mini-Europe is a series of big ideas inspired by a tiny theme park.

Mini-Tradition

Tradition is so hot for numbers. Since 1492. Since 1776. Since 1945. Tradition loves that shit.

Me: Since 1982.

Mini-Europe: Since 1989.

How many visitors to Mini-Europe are return customers? Has anyone paused at the Mini-Acropolis annually? Once a year for ten years? Twenty years? Brought their children, children’s children? I went two summers in a row, but may never go back.

In the opening number of Fiddler on the Roof, Tevye walks around Anatevka, his village in Russia, introducing the townspeople. “How do we keep our balance? That I can tell you in one word: tradition.” He says it dictates how they eat and sleep, how they wear their clothes. “You may ask, ‘How did this tradition get started?’ I’ll tell you…I don’t know. But it’s a tradition.”

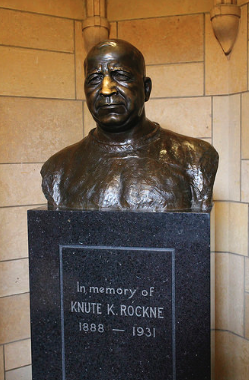

Traditions are famously sourceless. Why did my family eat pork and sauerkraut every New Year’s Day? My mother’s “Germanness.” Why the yearly pilgrimages to South Bend, Indiana to watch the Fighting Irish play football? My father’s “Irishness.” But the prominent Irish flag in my family’s basement felt like a disembodied mini-tradition by the time it trickled to me, fifth generation white American, whose tradition, if anything, was my complicity in the consuming and homogenizing of all tradition.

Tevye continues, “And because of our traditions, every one of us knows who he is and what God expects him to do.”

This is “who we are.” It’s “what we do.” Tradition’s phrases welcome and enslave. Identity pre-packaged and prix fixe. I outsource thought, appearance, activities, demeanor, and fate to my “we.”

Theorist Paul Ricoeur says tradition is the “interplay of innovation and sedimentation,” the old gets its Hollywood reboot each generation. Consider Florida Georgia Line’s country pop song, “It’z Just What We Do”: a forgettable minor hit in a niche market, but significant since it both perpetuates and updates tradition. The Confederate National Anthem begets Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” begets Florida Georgia Line.

The same photo of the same pose with the Mini-Leaning Tower of Pisa every year, but each time with a few more pixels.

Though the verses of “It’z Just What We Do” catalog a particular tradition, the chorus could read as justification for any group’s traditions. Substitute Fascists, Communists, Terrorists, any country in the EU for the “we,” and see if it rings true:

We might look a little crazy tonight / Hey baby, that’s all right

It’s our backwoods, boondock roots / It’z just what we do

Ain’t no way to make this up / When it’s running through your blood

There ain’t no hiding the truth / It’z just what we do

My skepticism has often left me “we”-less, or hopping “we” to “we.” Six years or so ago, I signed myself up to the avant-garde poetry “we,” and like any newbie to a tradition, enmeshed myself in its past, beseeched its elders for knowledge, in the hopes of one day adding my name to the list of people who continued the tradition. The Modernists beget the New York School beget the LANGUAGE poets beget the Conceptualists. But by enlisting in that tradition, I dismissed parallel traditions as aesthetically inferior, swathes of worthwhile literature left unread. It’z just what we do.

Tradition is so inescapable because it determines how to measure time. Every January 1st, tradition plops me back at Start for another round of Christmas, another repeat of Independence Day. Walter Benjamin says, “The initial day of a calendar serves as a historical time-lapse camera.” Is my memory so bad that I couldn’t remember without Days of Remembrance?

Even in my contrarian essay, I’m quoting one of the twentieth century’s preeminent contrarians, perpetuating a lineage. Though I come to every holiday with a knowing wink screwed into my face, I still celebrate. I may scoff at anyone staking claim to a “true meaning” of Christmas, or Independence, or a country, or a people, but I find true meaning in that scoffing, mostly since it unites me with others of similar opinion. We scoff together, but abstaining is still an anthem.

I was 12, sitting next to my father at a pep rally, the night before the Notre Dame Fighting Irish played a football game against some other “we,” when I first saw thousands act as one. A mass of blue and gold chanting “WE ARE (clap clap) N-D (clap clap) WE ARE (clap clap) N-D.” I couldn’t tell you the identities of the individual players or the content of the coach’s speech, all were subsumed by “we.” Exiting the arena, it was tradition to walk by the bronze bust of Knute Rockne, a former coach who died in 1935, and rub his nose for pre-game good luck. After so many years, so many games, tradition has disfigured the present, the statue’s nose rubbed raw, yet polished and shiny.

Mini-Death

Not all the small survive.

Just across town from Mini-Europe, I visited the Cinquantenaire Museum, yet another anthropological hodgepodge, where I stood on skeletons from the seventh century. Decomposed bodies posed under plexiglass, lit by LEDs, three feet below the floor. Three of them, each “buried” in their own faux-hole in the ground, all tiny, mini-people. Every generation physically shrinks into antiquity, as if Rick Moranis’s ray from Honey I Shrunk the Kids was pointed at dead bodies and left on, at its lowest setting, for thirteen hundred years. A sign urged me to not step on the “graves,” but mentioned nothing of their displacement or of how nice they looked in the energy-efficient lighting.

When my sister and I were 10 and 15, I remember wandering the Fort Indiantown Gap National Cemetery as my mother and father knelt next to marble, visiting with relatives. Half the field was a grid of grass and marble rectangles, the other half only grass. My sister: “Why are there no graves over there?” I could see the invisible For Sale signs.

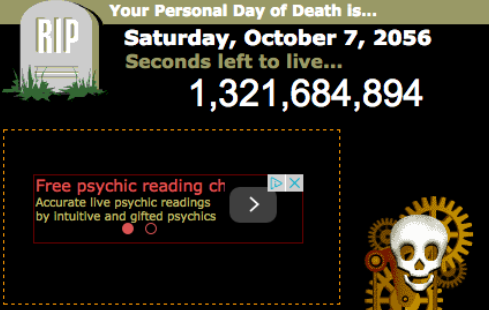

The site DeathClock.com tells me how long I have. I input my birthday, my relative level of happiness, my BMI, and whether or not I am a smoker. DeathClock tells me I will die on Saturday, October 7, 2056. The site also includes a ticking clock that counts down my seconds. I have 1,321,684,894 seconds.

By the time you read this, I’ll have less.

A few years ago, when I had more seconds, I spent two days delivering Yellow Pages. One book in a plastic bag at the door of every house in an upscale Northampton neighborhood. I wore a GPS tracking device around my neck. Back at the warehouse, the boss’s monitor showed him everywhere I’d been. Possible definition of death: when your GPS arrow stops moving. The transformation from a person to a location.

If I change my level of happiness from “Normal” to “Pessimistic,” my death date moves up to August 26, 2032.

I called my grandmother and asked her about her week. She said the Bishop of the Diocese of Harrisburg died on Tuesday. They buried him in the oldest cemetery in the city, next to the previous nine bishops. On Thursday, a truck full of diesel fuel exploded on the elevated onramp to Route 81. The driver survived, leaping to avoid the flames. It was a holy day on Thursday, and with rerouted traffic, it took her and my grandfather 25 minutes to get to church. “It’s been a busy week,” she said.

A mini-gondolier pilots a mini-gondola in an endless circle through the canals of Mini-Venice, and though his feet are submerged, he never breaks stride, escorting a loving couple, only their heads above water, who cling to each other as he paddles onward, not sinking, not afloat.