Gawker spent 9,000 words trying to justify its snarkiness. It failed.

The glad-handers, backslappers, and implacable throat-clearers are assembled in the Great Hall, draining mead from their goblets and offering each other well-earned handjobs. His apple cheeks pinkened with sincerity, Dave Eggers climbs atop the long oaken table and twirls about, gleefully kicking more food to the floor than a family of haters could eat in a week. He is dressed as Max from Where the Wild Things Are, because childhood is awesome. A rapt Joe Lieberman looks on and smiles his melted bologna smile. “Startling,” he says. “Stunning. Fiercely original.”

A fire roars in the hearth. Through a mouthful of roast pheasant, David Denby is sharing tales of his research among the savage peoples of Twitter.

“Is it true that they care nothing of the tone?” CNBC’s Maria Bartiromo asks. “Of civilized discussion and pragmatic centrist solutions?”

Denby is touched by her naïvete. “My dear. They don’t even care about the world’s greatest middle class or an end to petty grievances.”

Bartiromo reaches for her pearls but before she can clutch them, the walls of the Castle Smarm begin to shake. Flakes of plaster flutter down from the ceilings. A great disembodied roar echoes through the hall. “I am Gawker,” it declares, “and this is smarm’s reckoning.”

Eggers—emboldened, perhaps, by a glowing review from the super nice guys at BuzzFeed Books—shakes a defiant fist to the heavens. “You and what army?”

Gawker chuckles, ironically because duh. “ROTFL, motherfuckers.”

Words—9,000 of them—pour into the hall, rudely speaking out of turn and leering at the revelers with an unearned knowingness. The smarmers scramble to join Eggers on the table. Tears well in their eyes. The words snicker at this open display of sentiment. “I bet Death Cab changed their lives!” a word calls out. Sinister cackles bounce off the cold stone walls. The smarmers reach for each other’s hands, pressing sweaty palm against sweaty palm. This is it. The party’s over. There are so many words, and so many of them are handsomely arranged! They must be right. Right?

Did I just snark in defense of smarm? Or was I snarking at the tail-eating earnest pomposity of a 9,000-word snarker’s manifesto? Maybe I’m an agent of smarm who has armed himself with the weapons of snark? Who cares? Snark. Smarm. It’s mostly the same kind of bullshit anyway.

For a certain breed of internet creature, Thursday was a very big day. In case you’re not that kind of creature (and consequently have no idea what the hell I’ve been prattling on about), that was the day that Gawker published Tom Scocca’s 9,000-word treatise, “On Smarm.” It’s the kind of article that is calculated to be a Big Cultural Moment. Gawker—the net’s foremost Haus of Snark—has never put forth such an extensive justification for its famously snide tone, and Tom Scocca does a hell of a job casting aspersions on smarm, which he sees as the real poison in the country’s discursive well.

Here’s the tl;dr version of “On Smarm”: Americans are too ready to finger snark as the enemy of a real conversation. Snark—which the essay elevates to a never-articulated “theory of cynicism”—is a natural reaction to a culture of smarm. Scocca clarifies:

What is smarm, exactly? Smarm is a kind of performance—an assumption of the forms of seriousness, of virtue, of constructiveness, without the substance. Smarm is concerned with appropriateness and with tone. Smarm disapproves.

Essentially, smarm pretends to be the adult in the room. It presents itself as above the fray of snarkish insults. It recasts frank, honest criticism as rudeness, and endorses Thumper’s rule from Bambi: “If you can’t something nice, don’t say nothing at all.” What we’re left with are publicists in place of critics, journalists who get agitated when you call a corrupt corporation “corrupt,” and an important new books section that flat-out refuses to run negative reviews. Smarm is using a mask of civility and manners to shut down critique. Smarm is bad.

To which I say, no shit. But can we quit pretending that snark is an adequate response?

I (unironically) want to tip my hat to Scocca. At the risk of sounding smarmy, it’s hard to make 9,000 words as readable as he made “On Smarm,” and he & I hate a lot of the same things. I’m totally down with rudeness as a political tactic, and I think people who love books should love them enough to argue with them. But as you work through his essay, you’ll start to notice Scocca employs his own rhetorical dodges. Anything honest is claimed under the banner of snark, and snark’s enemies—a group that ranges from the Believer to BuzzFeed Books to Upworthy to everyone I name checked in this essay’s opening scene—are implicitly or explicitly accused of self-serving dishonesty.

In an incident I alluded to above, Alex Pareene of Salon (and formerly of Gawker) referred to JP Morgan Chase as corrupt during an appearance on CNBC. This irritated Maria Bartiromo, because she’s smarmy and awful and not a real journalist. Yay Pareene! Boo Bartiromo! Scocca, however, isn’t content to cheer honesty and jeer bullshit. In a weird attempt to give a point to Team Snark, he prefaces the incident by saying, “These terrible snarky people even go on television, sometimes,” as though Pareene had said that Chase CEO Jamie Dimon must have gone shopping at Louis Vuitton, what with those big leathery bags he carries around under his eyes. If simply stating that awful shit is awful counts as “snark,” we best get ready to declare Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela the snarkiest bitches on the block.

Scocca is just as sloppy when he populates the smarmy camp. Heidi Julavits is pegged as an “explicator of the niceness rule” because of a 2003 essay she wrote for the Believer challenging the “hostile, knowing, bitter tone of contempt” that was sneering its way into book reviews. This essay is quoted several times in “On Smarm,” but here’s a quote Scocca leaves out:

To be perfectly clear—I am not espousing a feel-good, criticism-free climate, where all ambitious literary books receive special treatment, just because they’re “literary” (I acknowledge the dubiousness of the term)—I’m simply asking that we read between the lines, and see what value systems these reviews are really espousing.

That smarmy idiot, suggesting that snarky critics ought to think critically about their own criticism.

Above and below this sentence, Tom Scocca is judging me for my smarminess.

In case you’re blissfully unobsessed with the tangled world of little magazines, the Believer was founded by Dave Eggers, best known as the author of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius and the perpetual antagonist to people who like their lit world rough & tumble. Eggers is Scocca’s “loudest Thumper of all,” just as he was the relentless avatar of positivity that n+1 very consciously attempted to define itself in against when it opened up shop back in 2004. The first issue called out the Believer under the headline “A Regressive Avant-Garde,” and the editorial condemned the “Eggersards” as “thoroughgoing, even prissy, moralists” who write in a tone that’s “wide-eyed, juvenile, faux-naif.” Though Eggers isn’t name-checked in issue two, the opening section assaults the literary kumbaya that he represents both to n+1 and to Scocca:

The essence of writing is that it’s expressive of ideas and technique—and the primary truth about other people’s ideas and other people’s art is that mostly they will be distinct from and opposed to your own. The guild mentality reinforces a sense that writers don’t do anything threatening, either to the general public or one another.

Substitute “smarm” for “guild mentality,” and you have something that looks a lot like Scocca’s argument.

But for n+1, the antidote isn’t snark. It’s honest and thoughtful engagement. This is where the world starts to fold back on itself. If we want to build two poles, an argumentative, sharp-elbowed one at n+1 and a friendlier one over at the Believer (the real Believer, not the straw man of Scocca’s essay), the charge that runs through them is an aspiration of sincerity. A.O. Scott saw this eight years ago, when he wrote that the magazines shared “a demand for seriousness that cuts against ingrained generational habits of flippancy and prankishness.” (Against snark, then?) Sometimes they fall short and get too enamored with their own cleverness (n+1) or cuteness (the Believer), but these slips are redeemed many times over by triumphs of honest thought and passion like n+1’s Occupy broadsheets and the Believer’s series on solitary confinement.

There I go sounding smarmy.

Snark is often classified as a postmodern sensibility. This is mostly because of the gleefully hip ironic distance it radiates, but snark is also postmodern in its penchant for the uncontextualized. “On Smarm” actively ridicules readers who question its motives or arrive with some outside knowledge. You take it on its own terms as a free floating document, or you’re smarmy. Quoth the Scocca:

A pause, now, for some inevitable responses:

– What did Dave Eggers ever do to you?

– Surprise, a Gawker blogger who’s never accomplished anything is jealous of Dave Eggers.

– Dave Eggers has inspired more people and done more good than you could possibly dream of.

That’s it. You’re getting it. That’s smarm.

Or, you know, that’s context.

Scocca hates some things that Eggers has said in interviews. Dave Eggers is prickly. He responded to accusations of selling out by claiming he says yes to opportunities because “No is for pussies.” He used to be a critic and now says, “I wish I could take it all back because it came from a smelly and ignorant place in me, and spoke with a voice that was all rage and envy.” His implication is obviously that people who are currently critics write from that same place in that same voice. There’s plenty to critique here. Go for it, Tom!

Scocca doesn’t stick to the arguments, though. He goes ad hominem. Eggers, the person, is “full of shit.” In fact, he loves shit so much that he sleeps on “bullshit-stuffed mattresses.” He is so thoroughly permeated by shit that Scocca is comfortable dumping on an Eggers movie he hasn’t seen and an Eggers book he hasn’t read “because God knows [Scocca’s] not reading or watching the whole thing.” The thing is, when you start attacking the person rather than the arguments, then it’s neither irrelevant nor smarmy to point out that Eggers is deeply involved in some great nonprofit work, or that a bad issue of the Believer is more substantive than the best month at Gawker. Snark wants to choose the shards of reality that everyone gets to play with, and it calls you smarmy for bringing other toys to the playground. (Smarm does the same thing; snark is just no better about it.) Snark isn’t good at talking about complexity. Snark scavenges for individual quotes and incidents, sharpens them with snideness, and uses them to shiv three-dimensional people. Snark disapproves.

Tom Scocca writes that smarm “is a kind of moral and ethical misdirection.” He’s right. The smarmy complain about “tone” to cover up their own nastiness. When Mitt Romney got caught writing off 47% of Americans as irredeemable, self-designated victims, he suggested that anyone who asked him about it was “focused on attacking a person rather than prescribing their own future and the things they’d like to do.” This is self-serving smarm at its grossest.

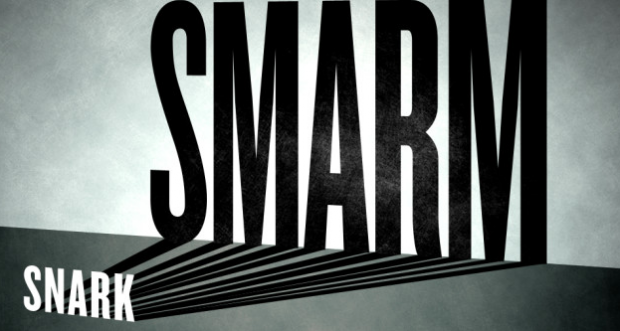

Funny thing, though. “On Smarm” is, among other things, one giant exercise in misdirection. You think snark is bad? Scocca asks. Well you should get a load of this other kinda sorta related thing that’s even worse! The essay tries very hard to paint smarm as snark’s inverse. It’s accompanied by a handsome little graphic of the word “SNARK” casting a shadow that spells out “SMARM,” and we’re assured that if we really think about it, snark “is reacting to smarm.” Really? Because it seems like it’s also reacting to Ke$ha’s nose job, some ancient MTV VJ who we all totally thought was dead, and a woman having a mental breakdown upon discovering her husband’s infidelity. And that’s just in the past week. On Scocca’s own website. Speak truth to power, y’all!

Snark isn’t a reaction to smarm anymore than it’s a reaction to literally anything else. My opening bit about the Castle Smarm—that’s snark reacting to snark. Snark is just a style of commentary, not a vaunted “theory of cynicism.” Its inverse isn’t smarm; it’s earnestness, and smarm is a shitty, self-serving performance of earnestness, not the whole damn thing. Even as it differs from it, snark isn’t categorically opposed to earnestness; it’s part of a toolkit that, without earnestness, is incomplete. They’re two non-exclusive ways of communicating. Both can be useful, and both can be awful. When used poorly, both are exercises in self-importance. Bad snark says, “I know more than you do, asshole.” Bad earnestness says, “It’s too bad you can’t feel as deeply as I do, and I pity your shallow existence.” Fuck both those guys.

The important line to draw isn’t between the snarkers and the earnest kids. It’s between honest engagement and self-serving masturbation. All-star snarker Stephen Colbert is on the same team as the sincere Jeremy Scahill, not as Perez Hilton. Perez is off in the corner with Jedediah Purdy, composer of “a defense of love letters” & Scocca’s smarmy whipping boy, and they’re too busy glaring at each other to notice there’s a world outside their antagonistic circle jerk.

From the best I can tell, Tom Scocca cares. Sincerely. “On Smarm” practically vibrates with his contempt for bullshit. I dug through his posts at Gawker, and when he gets snarky, he tends to spit his bile at targets that pretty much deserve it. His & my politics seem to mostly overlap, and I’ve got no interest in defending Upworthy’s business model of juicing the sugariest pellets of human feeling into viral pap, or in backing a literary conversation where I’m not allowed to get angry. Hell, Tom & I like the same writers! In “On Smarm,” he waxes affectionate for Hunter S. Thompson, George Orwell, and David Foster Wallace. “This belief that oblivion awaits the naysayers and the snarkers shouldn’t survive a glance at the bookshelf,” Scocca writes.

Wallace, especially, is someone I think about a lot when I try to sort out what a literary life should look like. Here’s a passage from his essay “E Unibas Pluram”:

The next real literary “rebels” in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Dead on the page. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that’ll be the point. Maybe that’s why they’ll be the next real rebels. Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk disapproval. The old postmodern insurgents risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship, accusations of socialism, anarchism, nihilism. Today’s risks are different. The new rebels might be artists willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the “Oh how banal.” To risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Of overcredulity. Of softness.

David Foster Wallace, “naysayer and snarker”?

The best art going is the stuff that shows us as the cracked, slimy, corrupt, and petty creatures we so often are. It maps the terrain of human ugliness in painstaking detail, and it doesn’t fall back on smarmy tropes of innate goodness or love conquering it all. So far, so snarky.

Yet despite all of this ugliness, great art dresses its subjects in real flesh. It presents even shitty people (and we are all sometimes shitty people) not just as venal buffoons or nefarious tormenters, but as the walking wounded (and we are all, to some degree, the walking wounded). It is merciless in tallying the ways that we can be awful, but sympathetic toward our halting, ham-fisted attempts to be better. Sins might not be forgiven, but neither is anyone’s humanity forgotten. You, me, Scocca, Eggers—we’re all packed onto the same sinking ship. The best art recognizes this, and doesn’t stop at stoking our rage at each other. It opens us to each other’s struggles and gives us a shot at escaping the self-obsession of callow snark & syrupy earnestness.

This is what’s behind Wallace’s determination to keep the cruise ship passengers and Midwestern churchgoers who populate his essays from becoming the nasty, butter-sucking rubes you’d see in a Bill Maher sketch. This is why Jonathan Franzen lets his characters drag themselves through filth and abjection for 600 pages, and then allows us to watch as they build some messy approximation of dignity and redemption by novel’s end. It’s in the moment where, staring into the precipice of fascist Europe, Walter Benjamin takes solace in the fact that the trials of all the downtrodden will live on “as confidence, as courage, as humor, as cunning, as steadfastness in this struggle, and they reach far back into the mists of time. They will, ever and anon, call every victory which has ever been won by the rulers into question.” This is where snark—fun, irreverent, angry snark—meets its limits. Even the best snark is only a half-measure. It keeps us inside ourselves. It flatters our intelligence, and, just as much as smarm, risks carving a line between the elect and the damned, the knowing and the mass of sheeple. Uncool, unhip, unGawker empathy—that’s our best hope at a full-measure.

“As the Bush administration went on,” David Denby writes, “the insufficiencies of snark became mortifyingly obvious.” That quote makes Scocca lose his shit. I haven’t read Snark, the Denby book “On Smarm” cites frequently and angrily. If Scocca is accurate when he paints Denby as representing right-wing lies and left-wing snark as equal partners in the disasters of the last decade, then he’s right to smack down that bullshit.

But you know what? The insufficiencies of snark are mortifyingly obvious.

No one with a firing synapse thinks that snark is responsible for Gitmo, or Abu Ghraib, or the soupy carnage the US has spilled all over the Middle East, or the writhing greed orgy that broke global capitalism. However, we live in a world where these things did happen, and we make choices in how we respond to them. Snark isn’t gonna cut it, not by a damn sight. Have you ever seen a social movement based on snark? Me neither. At most, good snarking can function like a smoke alarm, letting us know that the flames are licking at our door, but we have to remember that the fucking house is still on fire. The goal is to put the fire out, not to blog about how much we hate the smell of smoke.