“The President of the United States is calling–will you accept the charges?”

So Julie has come to San Clemente, the good daughter left to care for her father even when the rest of the country falls away. But when she gets to the house he isn’t there—not even the dirt of a man’s shoe on the cream-colored carpets—and her mother is talking only in distracted fragments. Her father left this morning after days of muttering, shaking hands and twitching eyes, and Pat did not stop him as she had so many times before. Julie cannot reasonably blame her for this, but does so anyway.

“Did he go far?” she asks.

Pat’s mouth twitches slightly. She lifts her glass. “Not far.”

“Where’s not far?”

“Well.” Pat stubs her cigarette out, leaving a smashed and ashy mess that looks like it could not have been made by her ladylike fingers. “That’s the $64,000 dollar question, isn’t it, dear? What’s not far? In this traffic, everything’s far from here. That’s why I don’t go out much. Because of the traffic.” She looks around, mouth slightly open but tongue lost within it; she looks at the thick, ugly drapes Julie has always hated, the matching velvet-embroidered couch, the whole room the yellow of faded bruises, rising bile. “What’s not far?” she says again.

“I’ll tell you what I know is far. Washington is far. Washington is a long way from this room.”

“He didn’t go to Washington.”

“No.” Pat looks out the window at the wide sea below, and then looks, finally—wide face startled—at Julie. “Oh, honey,” she says. “We really need to do something about your hair.”

Julie swats her hand away. “Later. So he didn’t go to Washington?” she asks, thinking: could he? And then: well, why couldn’t he, after all? There’s no law against that.

“No,” says Pat. “Why would he? That’s where he ended. No. All your father said before he left the house was that he was going to the place where he began.”

That’s all Julie needs. She has spent enough hours at her father’s feet, has listened in on enough of her parents’ fights, and lately has fielded enough long-distance calls at one o’clock, two o’clock, three o’clock in the morning—The President of the United States is calling, will you accept the charges?—to know what this means. Yorba Linda. Her grandfather’s failed lemon grove. The place where her father was born and that his family left behind when he was a boy, and that he has been talking about going back to since before the troubles began.

“Be careful around that friend of his,” Pat says as Julie heads for the door. “I think he’s a bad influence.”

When Julie finds him, the 37th President of the United States is standing barefoot on the dry, dusty ground of a grove in Yorba Linda, a lemon in one hand and a megaphone in the other. As Julie approaches him—seafoam green baby heels sinking a little into the dirt; seafoam green pocketbook clutched in both hands—her father turns to her and smiles. “Button,” he says. “What a surprise.”

“Hello, Daddy,” she says, and smiles the way she learned to do for photographers. He has never called her Button before.

The President reaches both arms out as if to hug her, then looks down, bewildered, when he realizes they are full. He looks at the megaphone. He looks at the lemon. He looks at both of them for some time, seeming to debate their relative import, and then, with a look of great reluctance, places the lemon in Julie’s hand. She opens her pocketbook and slips it inside.

“Daddy,” she says, slipping her arm through his, and feeling a heat that she is sure comes not from the sun resting on him but emanates from his very body, “it’s nearly five o’clock. Don’t you think it’s time to head home?”

He smiles in the way she would imagine someone smiling if she closed her eyes and said the word “fatherly” to herself, though it is not a smile she has seen on him much before. “Button, I am home.”

“But back to Casa Pacifica,” she says. “Back to mother. There.”

He bends slightly and kisses the top of her head, right where her hair parts and her skin is thinnest. “I have important work to do, Button. Your mother understands, just like she always has. It’s not easy being the President’s wife.”

“I know, Daddy.”

“Besides,” he says, gesturing to something behind her, “I would have been home hours ago if this son of a bitch could learn his lines.”

Julie turns and sees looming before her a figure dark enough to blot out the sun. She smells him before she can make out his features: sweat and hair oil and perfume sweeter than the icing on a child’s cake. The first thing she makes out on the face is a line of zinc spread down the nose, whose shape she can still make out beneath it—soft and slightly upturned and oddly regal. The nose is the same though the face is different, brown and wide and coarse as low-grade meat. The famous lips spongy and flaccid, the famous hair clearly a wig, and about to come loose of its moorings at that. But he is there before her: Elvis. Here in a lemon grove in Yorba Linda she stands in the company of the President and the King.

“Hello there, Julie,” Elvis says, extending a broad hand toward her. She shakes. “How’s the Big Apple treating you?”

“Fine,” she says.

“And that boy David? He doesn’t mess around with you any, does he? ‘Cause if he does, Julie, I know people. Hell, I’m real close friends with some people could put him where the sun don’t shine. I once sat down and had a mojito with the man that did Marilyn.”

The President, who has been facing away from them, framing a shot with his hands, looks at Elvis. “Kennedy?” he says. “Was it Kennedy?”

“I plead the Fifth,” says Elvis.

“If it wasn’t Jack, it was one of the others.”

“You forget, Capitan, college boys like that don’t like to get their hands dirty.”

“But what does it matter who did it? The money. That’s what matters. Where the money came from. Follow the money,” he says, and then looks momentarily confused, as if he senses the familiarity in those words but cannot connect it with anything true. Finally, he smiles at Julie—that fatherly smile—then turns away and walks off into the shade. Julie follows his path and sees a cheap wooden desk and chair set up between two lemon trees, a Super 8 camera resting on top of it, shaded by the slick green leaves above. She feels a little tired just as the prospect of asking what’s going on.

“I guess you think we look a little goofy out here,” Elvis says to Julie as her father walks over to the desk. Elvis’ forehead is streaming with sweat, and his wig seems to have slipped a little further.

“Well—”

“But when your daddy called me up and asked me if I wanted to take a trip out California way I just couldn’t say no. Y’see I always liked your daddy, Julie. Always liked you, too. Liked the whole family. That momma of yours reminds me a little bit of my momma Gladys—tough on the outside but soft as a rose petal inside, y’know? And that sister of yours. Trina. Tasha—”

“Tricia.”

“Tricia. That’s right. She’s just as pretty as a picture, ain’t she? Prettiest girl that ever lived in the White House, that’s for damn sure. Hey, you want to hear a joke I heard last time I visited you all? Heard it from the men’s room attendant. They always know the best joke. Lemme see if I can remember how it goes. Uh—yeah. Okay. What happened when Tricia Cox left the White House?”

“I don’t know,” Julie says. “What did happen when Tricia Cox left the White House?”

“The Washington Monument lays down!”

“Ha,” says Julie.

Elvis is laughing so hard she thinks for a moment she must have misheard him, that the line he gave her must have been the punchline to a much greater and grander joke, the kind that would explain why they are here at all. Tears streak down his already shining face, and he slaps his knee with a sound of wood hitting water. There is something almost childlike in his pleasure, but it is child trapped deep in something hard and pachydermal. Without thinking she reaches a hand out to steady him, and grazes with the tips of her fingers the fake rubies—she hopes they are fake—that adorn his chest.

He finally calms himself and wipes the tears away. “You like that, honey?” he asks. “That there’s a phoenix. Mythical bird that rises from the ashes of his former self. They named a city an Arizona after him. He’s a famous bird. Go ahead and touch him if you want.”

Julie trails her hand down the phoenix jewel by jewel. Later, she thinks, she can blame the heat for this, or her exhaustion, or the fact that she has always done what is asked of her so why stop now? Later, she thinks, but there is not later to think of and never has been. Everything that matters is now in the past. She trails her hand down the ruby phoenix and feels the heat of the body underneath, the creaking as it strains against the leather, the forced control of Elvis’ gale-force breath. She can tell he is pulling his stomach in, standing up a little straighter than he normally would. She replays his words in her head: He’s a famous bird. The famous voice gone water-heavy, a joke of itself, and she thinks of the voice she heard just a few years ago, the voice she listened to while watching his comeback special in 1968. Her father had just been elected but had yet to be sworn in. She had been raised first as the Vice President’s daughter and then as the daughter of the man who should have beat Kennedy, and by 1968 was sure she knew everything about what the next four years, and the four after that, would entail. She knew her father better than anyone, better than Tricia, better than Pat. She knew she knew him better, and thought this meant she knew what he needed, meant she knew what would make him well. She was afraid of the mistakes that he might make, of the quantity and of the kind, but she knew that the White House offered the kind of protection he needed, better protection than he had ever had before. And maybe the happiness of his newfound office–how could he, how could anyone, ever ask for more?—would dissolve the fear she saw in him, the fear and envy she so hated because she could see it so clearly in herself.

Kennedy was a Harvard man. You know what Harvard men are like. Pinkos or kikes.

Tricia was the pretty one. Tricia was the prettiest girl that ever lived in the White House.

Three weeks away from marriage—the younger of the two but the first to go forward—Julie watches Elvis’ comeback special. He has been famous for almost as long as her father; they have grown up together, she and Elvis, the eyes of America searching for their flaws. If they ever met, she thinks, they would have plenty to talk about. He might stop by the White House sometime. Her father wants to appeal to the young—she could convince him to invite Elvis to play a free concert on the lawn. Afterward, she could show him the roses in the White House garden, the cups and saucers in the china room, and then take him into the kitchen and offer him anything he wanted to eat. He would be surprised at her erudition, her ease amid such splendor. She would tell him about her courses at Smith. Her would tell her about Graceland. She had read in a magazine article once a list of all the foods he liked to keep there: hand-squeezed orange juice, a case of Pepsi, three bottles each of milk and half and half, freshly made brownies and banana pudding, three packs of Juicy Fruit gum. She would surprise him by having all of his favorite things there, hidden behind her father’s cartons of cottage cheese, and they would make a picnic and take it out to a secluded part of the lawn. They would get to know each other, and they would find that they were the only people who really knew what it was like for each other, what it was like to live surrounded by expectations they had not chosen for themselves, and that all they really wanted was a way out.

Finally, their talk would end. He would look into her eyes and she would look into his, and he would know how to do the rest. He would tilt her chin up and kiss her gently, a man of endless appetites finally going slow. That was how she had seen her father all the times he kissed her mother goodnight: a man of endless appetites finally going slow. That was all she wanted. Two or three seconds at most. He didn’t have to marry her. He didn’t have to take her to Graceland. Just two or three seconds of grace.

By the time Elvis finally came to the White House, two years later and not long enough for a trip to the garden or the china room or even the kitchen, Julie was out of town, speaking at a national Girl Scouts meeting. For a moment she thought of canceling, coming home and seeing what she would find there. But she stayed the course: she was a married woman, steadily moving forward in the only life she had ever been able to live.

Now, Julie presses her fingers against the sun-hot jewels of Elvis’ jumpsuit. She is suddenly tired, and has an urge to press her forehead against his chest, to let him hold her there. She is almost sure he would. Instead she looks up at him and smiles, the same diplomatic smile she learned during the early years of her father’s presidency. “It’s very nice,” she says.

“Nice! You’re tellin’ me. You know how long this took to make?”

“No.”

“Well—neither do I. But a long time, that’s how long. And it cost a pretty penny.”

Julie sees the President out of the corner of her eyes. He is brushing his hands off, and then he is as close as he ever stands next to anyone, and then he is closer, putting his arms around her and Elvis, pulling them into a huddle. “We’re ready to shoot,” he says, a vaguely ministerial air about him.

“Is that what you’re doing?” Julie asks after he’s pulled away, doing her best not to sound as exhausted as she feels.

“Well, of course, Button. What did you think we were doing?”

“Picking lemons?”

“No, no. If we wanted lemons we would go to the store. We’re important men. We have stories to tell. Something to contribute to the world. We have something much better to do.”

“I thought you were going to write your memoirs.”

“Well, these are my memoirs. In a way. You see, Elvis has graciously agreed to star in The Man from Yorba Linda: Virtue Victorious—The RN Story.”

“That’s just one title?” Julie asks. The President nods, and Elvis looks like he wants to say something, but does not. “Who’s he playing?”

The President laughs as if at the antics of a small child. Which, she supposes, he more or less thinks she is. “Me, of course.”

“You?”

Elvis shows Julie his profile. “Don’t you see the resemblance?”

“No.”

“Well,” says the President, “it isn’t a perfect match. But we make do.”

“How long have you been doing this?”

“A week,” the President says, at the same time that Elvis says “a month.”

The President looks over at him. “If you want to go back to Tennessee,” he says softly, voice graphite-smooth, “to your mansion and your parties and your drugs, then you can. If you want to win the American people back by playing a real American, you can stay here with me.”

“No, no, no,” Elvis says, and his voice, Julie is surprised to hear, is almost fearful. “I’m with you, Capitan. But, well, why do we gotta film it out here?” He mops his forehead, delicate as a regent, then give his handkerchief to Julie in a gesture she recognizes from his concert broadcasts. Do with this what you will. His hand glitters with unaccustomed movement, the sunlight catching each finger’s ring and sending its brightness into her face. This is how he beds women these days, she thinks—by stunning.

Julie thinks pictures her husband back home, of wide, toothy grin, his skinny body, and his skin that sometimes flushes rosy as a child’s. She thinks of Elvis as he was when she was a child, and how her father strode into the room one night as she and Tricia watched him on Ed Sullivan, switched the television off and strode away without a word. How they had sat there looking at the blank TV screen until Pat came in and told them to get straight into bed for goodness’ sake because it was almost nine! Julie looks toward her father, and the blinding falls away. She puts the handkerchief in her pocketbook, beside the lemon.

“How many times do I have to explain this?” the President says.

“At least tell Julie, man. I bet she wants to know.”

“I have some idea,” Julie says quietly, but her father is already launching into his speech, running his hands through his hair, closing his eyes, searching for the long sequence of words that will make all of this make sense. Finally, he looks up at them.

“Follow me,” he says.

He leads them over to the desk, lifts up—arms shaking a little—two folding chairs he has lain in the shade of a lemon tree, unfolds them and sets them up for Elvis and Julie. Then he sits down behind the desk—its cheap false-wood surface peeling away and little by little allowing her a view of the pulp and caught air that make up its insides, Julie’s mind pushed towards the shining hulk of a desk he once sat behind in the White House, the same desk now occupied by Ford—and shoots his sleeves and rests his hands in front of him. Presidential. He is still presidential. A disgraced man with feet sliced by the hard ground of a dusty and drought-tortured lemon grove; a man who was only ever good at one thing in life—certainly not husbanding or fathering or enjoying the life spread out before him, but one thing, you couldn’t argue that—and who lived to see that one thing unceremoniously wrenched away, two hundred thousand dollars and a decade’s worth of jokes left in its place. But still when he sits down and folds his hands and looks up at them, they have no choice but to sit down before him. They have no choice but to show the respect that they did not know until that moment would weigh so heavily upon them. They sit.

“As you know,” the President says, looking not at either of them but between them, in the direction of a nonexistent camera, “I was born in Yorba Linda, California the son of a roustabout who had come from the Middle West in search of the riches promised by the golden state. He never found those riches, but the journey he made allowed for the birth of his son, Richard, and for the eventual journey that young Richard would make from the humblest of origins to the hallowed halls of America’s greatest corridors of power, and eventually to the White House itself. I will be the first to admit that in recent months I have suffered setbacks. My ambitions have perhaps been too broad, and my love for the American people too great. And perhaps, too, they have begun to feel my guidance as a burden to them, and have yearned for a different kind of leader, a leader who does not take their interests to heart, and who sees them not as his adored children but as his equals. All this I can accept. A man does not earn the nation he is chosen to lead, but is thrust into power and forced to lead as well as he can with what tools God has given him. I accept the changes that have swept across this great nation, and I know that it is only a matter of time until the young Americans, and those who follow the young Americans, see that they have taken things too far, and that they need a leader strong enough to guide them home. When they are ready for me, I will be ready for them. And in the meantime, it only makes sense for me to come back to the place where I began, to Yorba Linda, California, and to the lemon grove that once belonged to my father, God rest his soul. Here is the place where I hope to learn from my missteps and come to more fully understand how I must guide you, my countrymen, when you choose to make me your president once more. Thank you, and good night.”

“What he means,” Elvis whispers, leaning towards her, “is he thinks he began here, if you see what I mean. That this is where his momma and daddy—y’know.”

Julie nods. She refused to be scandalized by a man who has been famous since she was in footy pajamas.

“Anyway, that’s the long answer,” Elvis says.

“Is there any other kind?”

“Not with your daddy.”

The President looks up from the imaginary papers he has been thumbing through. “Your turn,” he says to Elvis. “Let’s finish this scene. Pick up where you started.”

Elvis gets up to sit behind the desk, and the President takes Julie by the hand and picks up the camera by the other, setting it up on a tripod about ten feet away, where it sits in roughly the area he was gazing toward.

“I bet you’ve never been on a movie set before,” he says to her, then flicks a button on the camera—it is an amateur’s model, the kind white-collar fathers buy to take video of their children at play—and calls “Action!”

Elvis begins. He looks up at the camera and intones, in a voice that is not a bad approximation of the President’s: “I want you to remember that no bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other poor dumb bastard die for his country. Men, all this stuff you’ve heard about America not wanting to fight, wanting to stay out of the war, is a lot of horse dung. Americans traditionally love to fight. All real Americans love the sting of battle. Americans love a winner and will not tolerate a loser. Americans play to lose all the time. I wouldn’t—”

“Do it again,” the President calls.

Elvis looks up. “Huh?”

“Do it again. You flubbed it.”

“No I didn’t.”

“Yes,” he says, a glint of the old rage coming out in his eyes, his bared teeth, “you did, you crawdaddy-eating bohunk. You said ‘Americans play to lose.’ ‘Americans play to lose.’ That’s not how it goes, now is it? I’ve seen the picture. You’ve seen the picture. What does he say? He says ‘Americans play to win all the time. I wouldn’t give a hoot in hell for a man who lost and laughed. That’s why Americans have never lost and will never lose a war. Because the very thought of losing is hateful to Americans.’ That’s what he says. We both know that. Now do it again, and get it right.” He stares at Elvis a moment longer, then stalks off into the trees, the sweat-stained breadth of his back disappearing into the shade.

“He’ll be back in a minute,” Elvis says. “He’s just temperamental. Most directors are.”

“Most presidents are,” Julie says, walking over and leaning against the edge of the mocked up Wilson Desk.

“You don’t say?”

“Well, sure. How many have you met?”

“Just your daddy.”

“Not even Eisenhower?”

“Nope. But he heard from a lotta young ladies after I joined the army. They thought if they went straight to the big man himself he might save my rotten hide. Turns out he didn’t have to. Too bad.”

Julie turns to look at him closer. He is staring into his lap, and she sees his thumbs are trembling slightly, the rest of his fingers knotted together as much as the rings allow. She does not think, as she reaches out to rest her hand on his, I want to touch this man, but I want to know what this man feels like. The heat that rises from him is angry as a beesting. With some trouble, he pulls one hand free from the other, and rests it on top of hers.

“What part of the movie was that?” she asks.

“The end. We’re almost done.”

“What’s the end?”

“The resignation speech.”

“But that’s not how it went,” she says, thinking: Julie, of all things, you want this to make sense?

“I know,” says Elvis.

“Isn’t it from something? It’s—”

“Patton,” Elvis says. “We’re not much good at writing movies. I guess you found us out.”

“The whole thing is Patton?”

“There’s a little from It’s a Wonderful Life at the end, but that’s about the size of it.”

“Why aren’t you just doing the real speech?”

“Why not do something else? It’s a movie. Besides, it was your daddy’s idea. A movie can end however you want, even if it’s about real people. And besides, he hasn’t ended yet. The story ain’t over. Any end would be a lie. So why not a good one? All the best endings are made up, honey. If there’s anything I know by now, it’s that.”

Julie takes her hand away. “I don’t think that’s true.”

He looks her up and down. “How old are you, honey? Twenty-one? Twenty-two?”

“I’ll be twenty-seven in a week.”

“Twenty-seven. That’s a hell of an age to be. You’re smart, you know, figuring that out. But what should I expect from a college girl?” He smiles, but not at her. “You know what I was doing when I was twenty-seven?”

She ticks back the years in her head. “Well—”

“It was 1962. I remember it better than I remember yesterday. Tastes, sounds, colors, everything. I hadn’t married Priscilla yet. She was still a black-haired little girl in love with me. I had my birthday party in Las Vegas. Filmed three movies that year. There was no tiring me out. I went to Hawaii and a thousand screaming girls mobbed me soon as I got off the plane. Stole my jewelry. Nearly tore me in pieces. Woulda been better than this.” His gaze slides over to her, and he smiles. “But probably too young to understand any of that.”

She thinks she must understand it even better than he or her own father does, that even her mother did not hear the things she heard, or if she heard them was not able to believe they were true. Girls are the ones who know these things; girls are the ones men tell all their problems to, when they think they are sleeping or unhearing with love or simply cannot understand a word of it. She understood everything. What she didn’t understand was how they had arrived at this place, and by what road. There were so many flawed men in the world, and so many who were never as hated as her father. And there had to be a greater reason than coincidence to explain why he was there when the country needed to hate someone, and some greater reason than his own modest flaws to explain why he gave them so much to hate.

The President is walking toward them now, his arms outstretched, the early evening sunlight slanting through the spaces between the trees and falling on him as he passes by. “You ready to try it again?” he asks.

“All right, Capitan. But after this we call it quits for the day, right? I got a can of Mai Tai mix with my name on it back at the motel.”

“Well,” says the President, “It might not take too long. I’ve got a new idea, you see, and I think it’ll really knock your socks off. Yours too, Button.”

Julie smiles, feels the lump of the lemon in her pocketbook.

“Since you’re having trouble with your lines, I think we should change the end of the resignation speech to a song.”

“You gotta pay me extra if you want me to sing,” Elvis says, managing a straight face for a few seconds before exploding into laughter. It is all a fantastic joke. The President looks carefully at the air around him, as if searching for flies.

“Which song?” Julie asks.

“Your choice,” says the President.

“Well, then, it’s gotta be ‘Suspicious Minds,’ don’t it?”

The President looks confused, then slightly disappointed. “Of course,” he says at last. “I’m ready when you are.” Always the politician.

Elvis pulls his guitar from beneath the desk. “Thought I’d need this,” he says, smiling in a way he must think is wolfishly becoming. The President goes back behind the camera, and Julie leaves the desk and stands beside him, reaches up and squeezes his arm. He doesn’t seem to notice.

“Action,” he says, in a voice so quiet she can barely hear it.

Elvis begins to play. He comes out from behind the desk and sits precariously on top of it, gazes into the camera and turns on the charm. He knows what he is doing now. He is safe. We’re caught in a trap. I can’t walk out. Because I love you too much, baby.

The song reaches its crescendo—Oh, let our love survive—and the President yells, “Cut!” Miming a slashed throat as he must think real directors do, stepping out in front of the camera without turning if off, striding over to Elvis and all but taking the guitar out of his hands.

“Watch it, man.”

“Think of another song,” says the President.

“You wanna give me a clue or something? I don’t have a lotta songs that fit the profile.” The President does not react to this. “I mean–no offense, Captain–most of my songs are about love or Jesus. Not a lot about what you did. You know?”

“And what,” the President says, “did I do?”

“Well–y’know,” Elvis says, reaching back and scratching his neck and casting his gaze downward. Somewhere, Julie thinks to herself: there it is. At least he can still inspire fear.

“No,” says the President. “I don’t know. What did I do? I served as president of this Godforsaken nation for six years. You sang your little songs and made all of them love you. So maybe tell me this instead—what did you do? What did you do? I’d like to know. I’d like to know how—”

“Sing ‘Unchained Melody’!” Julie shouts.

Both men turn to her.

“What?” says Elvis.

“What?” says the President. She does not think she has ever raised her voice to him in her life.

“Sing ‘Unchained Melody,’” she says.

“Why?” says Elvis.

“Why not?”

“It’s a love song,” says the President.

“It’s a good song,” says his daughter.

“It ain’t my song,” says Elvis.

“You sang it plenty,” says Julie, who without thinking has taken the lemon out of her pocketbook and is holding it now in her fist, feeling not just its shape and its weight but its strange warty texture—not at all like the thin-skinned lemons they sell at the local supermarkets, so good for lemonade—and digging her nails into its bitter pith. “Why not sing it now?”

“Why should I?” says Elvis.

“Because I want to hear it. That’s why.”

And the old entertainer’s instinct takes over, and this is reason enough. Elvis puts his guitar down in the dirt and sits down behind the desk. The President watches, waiting.

“This really sounds best on a piano,” Elvis says apologetically, and then without further introduction pushes his sleeves up and begins to run his fingers over the peeling wood veneer, searching for the chords that will bring him home. He begins to strike the imagined keys, first gently, then with a force that is almost enough to make music. The President stands by the desk and watches him for a few moments, then turns and walks back toward his daughter, puts his arm around her, and turns the camera back on.

Finally, the great man sings. Beneath the fat of his swollen old voice—creaking with age and overuse and the exhaustion that a single day has brought to the man who once seemed too full of life to really be alive at all—there is something youthful, useful, and sweet.

Oh, my love, my darling, I’ve hungered for your touch a long lonely time. And time goes by so slowly, and time can do so much. Are you still mine?

The President puts his arm around his daughter’s shoulders, pulls her in against him and turns toward her. “Julie,” he says, “I have a wonderful idea.”

“What?”

“Go over and dance with him.”

“Now?”

“Of course.”

“Why?”

“I want you to be in my movie.”

The same word, the only word, again. “Why?”

“Because in this light you look just like your mother, and she deserves to be in the movie, too.”

She looks to Elvis. A drop of sweat falls from his forehead onto the desk, but if he notices it doesn’t matter; his eyes are closed, his hands working on a mute tremolo. Lonely rivers flow to the sea, to the sea, to the open arms of the sea.

Julie moves out from beneath her father’s heavy arm and walks into the frame. She imagines for a moment how she must look to the camera’s eye, the cool green of her moving into the arid land, and then how she must look as she comes to stand beside Elvis, and how she looks as Elvis stands up from the desk and puts his arms around her, the shape of her body gone, and whether the camera or her father can hear him as he keeps singing, the imagined piano gone and the voice now tenderer, soft as the gentlest of mothers’: Lonely rivers sigh, wait for me, wait for me. I’ll be coming home, wait for me.

Her hands have been resting on him as if they are at a cotillion dance, and now she puts them all the way around them, feels the bulk of him, feels the hum of his voice, his breath, his sweat as he lets his chin come to rest on the crown of her head. This is what all men come to, what all men will be. This is the truth to be found in every book and every poem she read in all her years of schooling, but it is nowhere to be found in the national news, cannot be learned from Woodward and Bernstein or MacNeil and Lehrer, is not in any newspaper or television show nor anywhere but in this lemon grove in Yorba Linda, California. And in this way, Julie thinks, he—her father, the President, the most hated man in America—is right. He is the one who is telling the truth, and the truth will be waiting when the people of America are ready to hear it. They will come to this. She will come to this. We will all come to this. There is nothing, in the end, but this. The man from Yorba Linda never lied.

As she and Elvis turn in the dirt—he still as graceful a dance partner as she always imagined him to be—she opens her eyes and looks at her father, his hands clasped tight and his eyes burning in the late afternoon sun. He is looking not through the camera but straight at them, straight at his daughter, and then up to Elvis’ face.

“Kiss her!” he calls.

Elvis turns to him. “What?”

“Kiss her. The movie needs a kiss. Or—wait. Some dialogue first. Elvis, repeat after me. You look at her and say: ‘Pat, you’ve stayed by me all these years.’”

Elvis looks down at her. “Pat, you’ve stayed by me all these years.”

“‘You were my wife and my First Lady, but most importantly you were my true friend. I have you to thank for everything I’ve gained in this life, and you to thank for everything I still have. I love you, Pat.’”

As Elvis recites his lines Julie thinks for a moment of her mother, sitting alone in Casa Pacifica, smoking and coughing, coughing and smoking, and waiting for her husband to come home. He will be home soon enough, she thinks. If not tonight then tomorrow, and if not tomorrow then the next day. He has always come back to her after every loss, and that alone makes her love her mother more than anything else ever has.

“I love you, Pat,” Elvis finishes. He is looking straight at her. In all the movies and all the specials she ever watched of him, his eyes never looked so blue.

“I love you, Dick,” she says.

He does not need more prompting. Taking her chin between thumb and forefinger he tilts her head up slightly, bends down, and kisses her. Behind the salt of his sweat there is a sweetness, and then a stillness like the air dying at the end of another day in Yorba Linda; like all the cups and saucers in the White House china room sitting untouched behind their glass content to silently bear the secrets of all the tasting lips and grasping hands that have touched them term by term; like a taped conversation coming to its clicking, static end. Julie thinks of her father watching them, of her mother at home, of Elvis’ ex-wife and baby daughter, a child now and about the same age Julie was when she realized just what her father did and what made him different from the fathers of all the other girls she knew. She thinks of all the women Elvis has bedded and will go on to bed, and of whether he kissed them the way he is kissing her now, and whether she will ever be kissed like this again. She thinks of the famous bird, of David waiting for her at home, and of how long he will be willing to wait for her if she puts him to the test. She thinks again: this is what all men will come to, and then she stops thinking and pulls closer the King’s ruined body and smells the breath of the lemon grove as it works its way around her, under her dress and flush against her skin and into her hair. She will smell it for days afterward, and it will not fade away until she has left her father safe at home and flown back to New York and gone into her fine white bathroom and taken off her clothes and looked at herself, the breath of the lemon grove falling away from her body, loosed and pacing as a panther, and filling the entire room.

____________

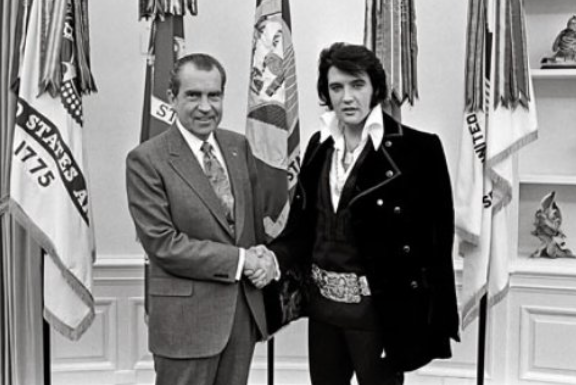

Featured image by Ollie Atkins, courtesy of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.