The story behind the story.

Every book has its own texture, materiality, and topography. This is not only metaphorical; the process of creating a novel produces all sorts of flotsam–notes, sketches, research, drafts–and sifting through this detritus can provide insight both into the architecture of a work and into the practice of writing. Blunderbuss is excited to inaugurate this series, in which we ask writers to select and assemble the artifacts of a book in a way that they find meaningful and revealing, and we are proud that the first installment belongs to our own fiction editor Sara Nović and her debut novel Girl at War, released today by Random House.

Girl at War tells the story of Ana Jurić, a ten-year-old girl whose life and nation are upended by civil war. Moving through time and space–from 1991 to 2001, from Croatia to the US and back again–the novel artfully renders the weight of war and the persistence of memory. It is at once harrowing and intimate, unrelenting and understated. Through Ana, we see history not as textbook abstraction or as intrigue in the halls of power, but as a fact seared onto the hearts of real people.

–The Eds.

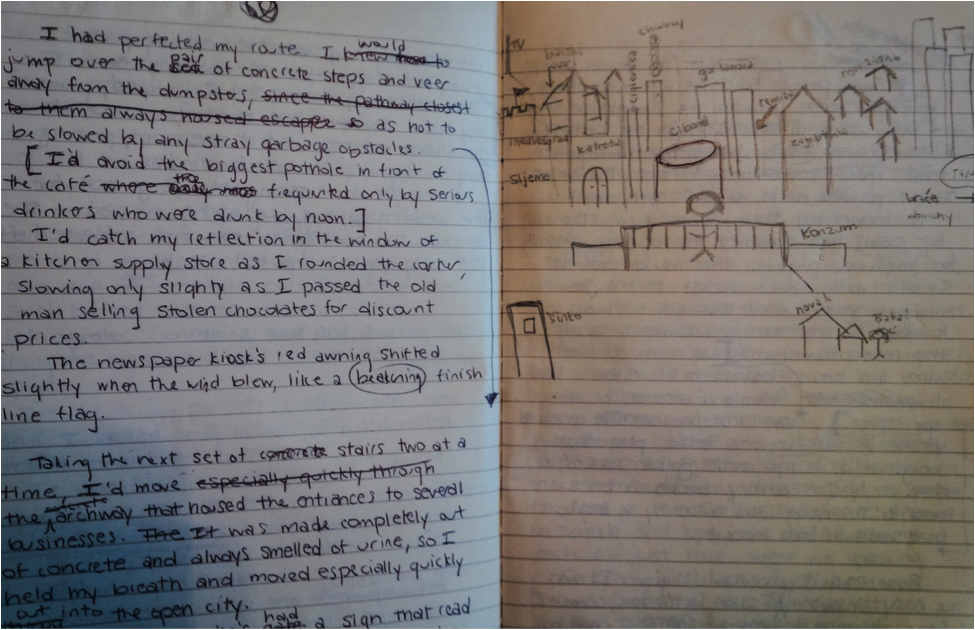

I write by hand, so pieces of Girl at War live in all these notebooks.

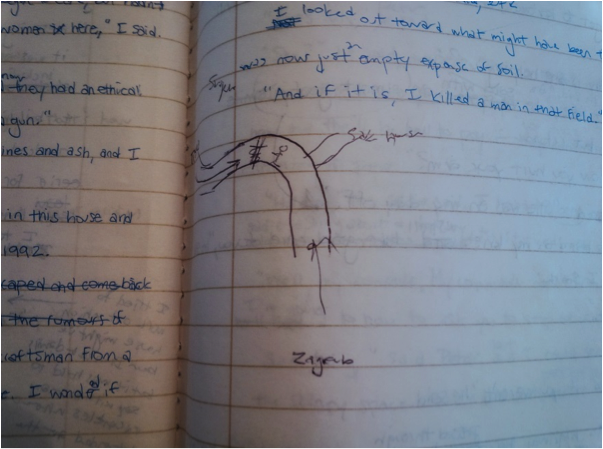

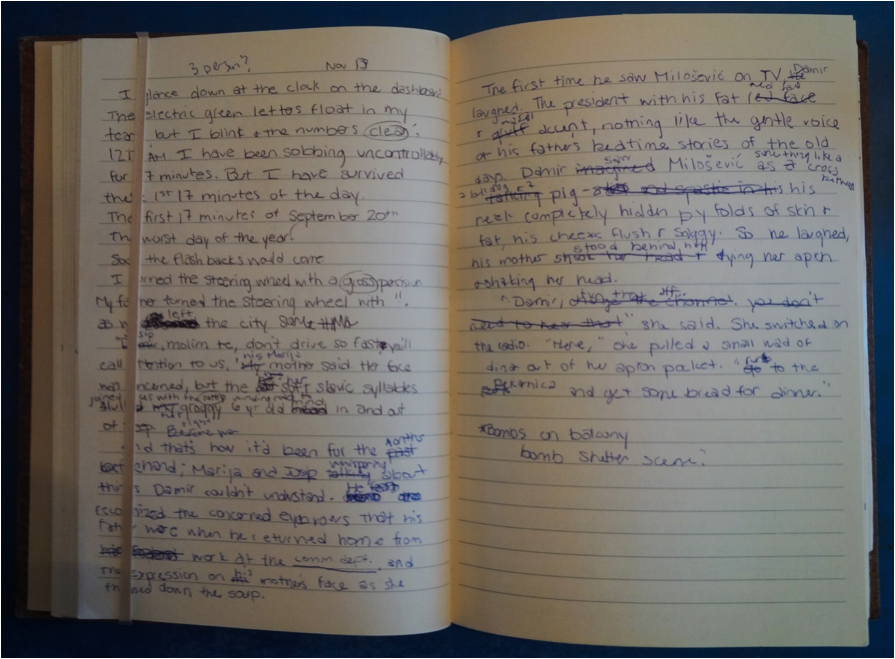

I think this is the first appearance of what would become the novel’s characters, in a notebook from 2005. The project was a short story first, in the third person, about a young boy’s traumatic past and his inability to deal with it in America years later. The character, Damir, eventually became Ana, the protagonist of the novel, and the point-of-view switched from third to first person, but much of the original description from this story remains the same, and serves as the basis of the climactic scene in the end of the book’s first section.

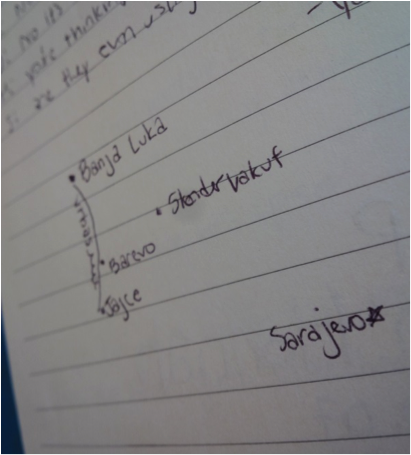

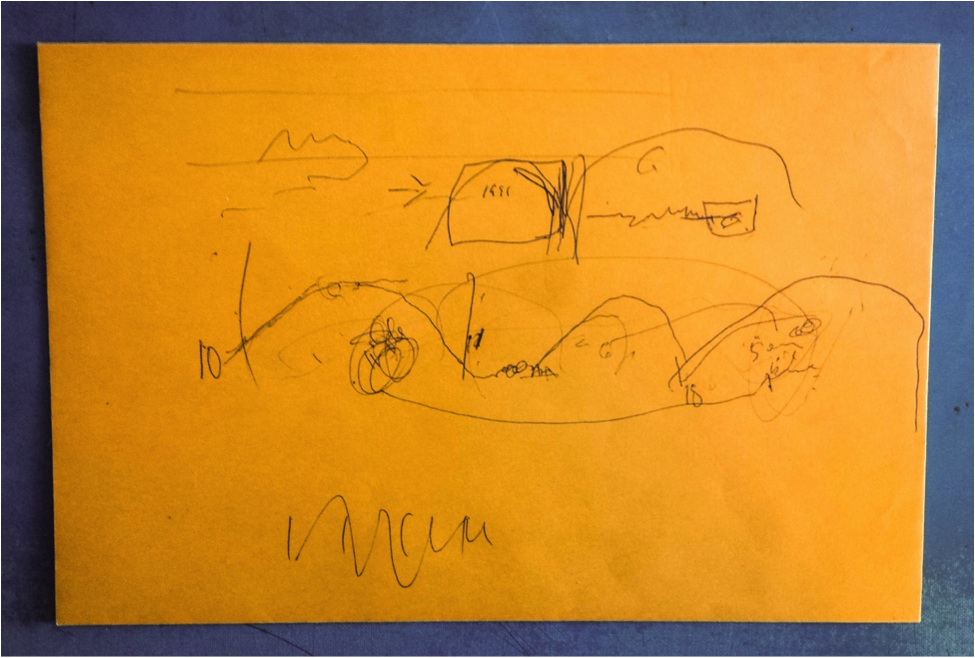

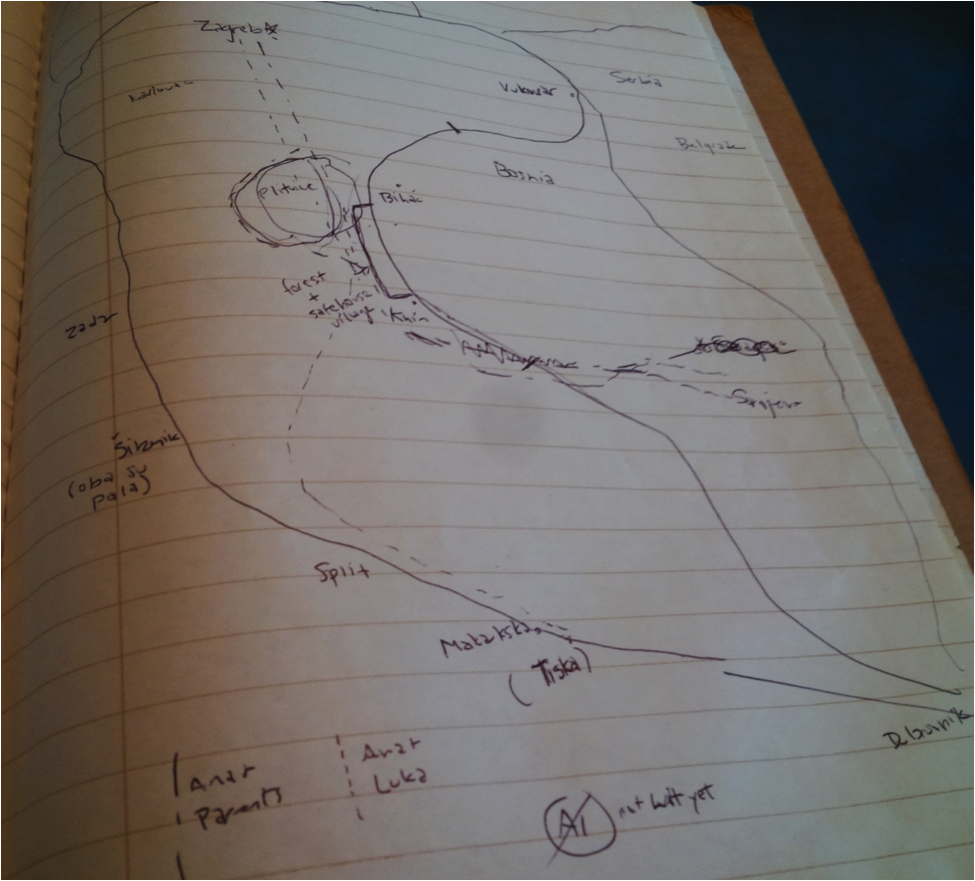

Road and highway construction were big points of contention in Yugoslavia in the period leading up to the war. Those in power, in Belgrade, were keen to build roads horizontally across the country to provide Serbian access to the Adriatic Sea, leaving Croatia largely unconnected with itself from the north to south. Because this was arguably a factor in inciting the conflict, and because certain roads facilitate key plot points in the novel, I did a lot of research on which roads did and didn’t exist in 1991, and have a few maps in which I tried to work out Ana’s family’s journey from Zagreb to Sarajevo.

(Above): A couple more maps of road directions and roadblocks.

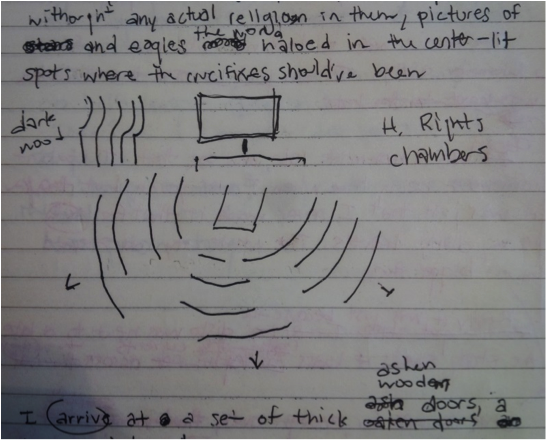

(Below): A diagram of the UN headquarters in New York City.

And purely for entertainment value–this Bosnian woman and her poker ring aren’t in the final draft of the novel, but apparently on a slow day waiting tables at Friendly’s she made the cut.

Ana is very much in love with Zagreb as a child, and one of the ways she escapes the pressures of war and family life is to go out on the balcony and look at her city. I wanted to paint an authentic balcony view for the reader from the neighborhood in which Ana lives, so while visiting Zagreb, I drew out an accurate panorama and worked my descriptions off this picture.

Additionally, the page on the left shows what became the opening scene of the novel (though I didn’t know it then).

The novel’s working title for a long time was “Oba su Pala” or “They Both Fell.” (It’s now the title of the first section of the novel.) The phrase comes from some of the most famous footage of the war, what which was played on the news on a loop as a sign of Croatia’s victory despite limited resources. In the novel Ana happens to watch it on TV with her mother, and I watched it on YouTube about fifty times to write the description of it.

One of the things I struggled with while writing this novel was the structure. Because of the nature of trauma and memory, I knew I didn’t want the narrative to be chronological; however, I was having trouble finding the right place to start the story. The big break came when, during the MFA, I expressed my organizational frustrations in a meeting with Sam Lipsyte. Sam hadn’t read the novel, but he graciously let me talk at him about it for a while, and he drew this picture as I did. When he handed it back to me, I realized what I had to do; the four humps became the four sections of the novel as they are now. I should’ve known it would take a semi-illegible map to sort it out, given how many I’d drawn over the course of writing the book!

______________

Image by Hayley Thornton-Kennedy.