A look at the dark humor and bright young things of Bulgaria’s art scene.

Before he died, my grandfather shared a Bulgarian proverb with me: “It is better to be the anvil than the hammer,” but he got it wrong. Anybody who knows the phrase would correct it to say, “it is better to be the hammer than the anvil,” because who would want to spend their lives being beaten by others? Despite the “correct” ordering of words, I’ve always felt that the anvil was a much more appropriate metaphor for my grandfather and the Bulgarian character he embodied: unwavering strength in response to battery from outside forces. Whether it was the Ottomans, the Communists, and now the former Communists and the mafia, the arduous history hardened the Bulgarian people allowing for their spirit to remain unbroken. Sariev-Contemporary Gallery in Plovdiv, the nation’s second largest city, is an example par excellence of Bulgarian resilience, innovation, and optimism.

I met Vesselina Sarieva in August 2014 while she was visiting New York City. As we sat in the backyard of a Brooklyn bar glowing with string lights, she told me about the countless projects, collaborations, and initiatives she has launched in Bulgaria and in Europe more broadly. In light of the Museum of Modern Art’s recent exhibition Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980—which doesn’t include a single Bulgarian artist—I asked Vesselina if we could speak more about contemporary art in Bulgaria and her activities in Plovdiv.

In 2004, Vesselina and her mother Katrin Sarieva founded Sariev Gallery, which originally exhibited photography and contemporary ceramics. By 2011, the gallery’s mission had expanded to include all variety of media, which prompted an official renaming to Sariev Contemporary. In addition to the gallery, the Sarievi women have established two additional organizations: the Open Arts Foundation (2007) and the artnewscafe (2008). This integrated model allows them to synthesize many aspects of Plovdiv’s cultural scene—the gallery provides an opportunity to exhibit thoughtfully curated art shows; the artnewscafe is a place for young people to engage with art, culture, and music, and is the only public institution in Bulgaria that subscribes to international art magazines; and the Open Arts Foundation organizes a wide array of cultural and educational programming, such as the “Introduction to Contemporary Arts” program in Plovdiv and Sofia. While each initiative independently contributes to Plovdiv’s culture, the combination of the Sarievi’s work produces new possibilities in art, communication, and internationalism. Vesselina explained that growing up, she experienced a sudden transition from a thoroughly Russian-dominated culture during the Communist rule to a more diverse, dynamic milieu after the collapse of the Soviet Union. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, her father, Vesselin Sariev, began working with artists in Chile to produce SVEP, a magazine for visual and experimental poetry. Remembering the joy of receiving art from across the globe, Vesselina maintains that her biggest dream has always been to communicate with the world, and to show the world Bulgaria’s culture.

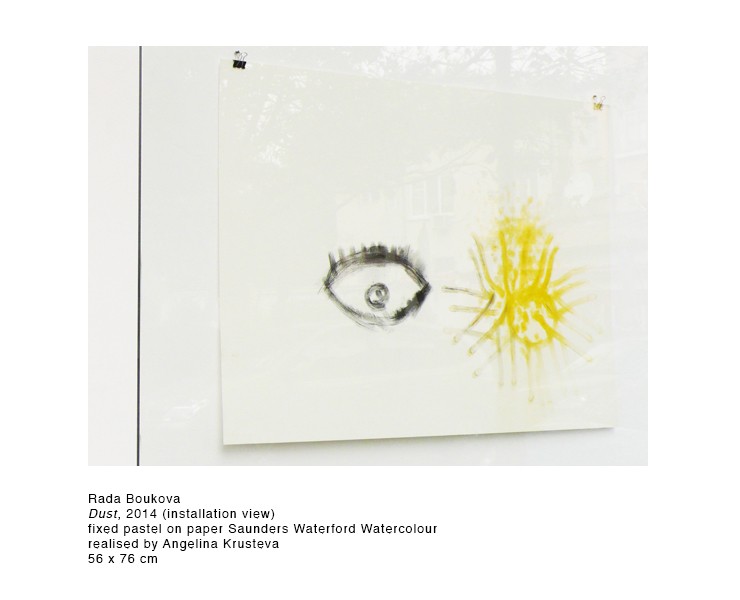

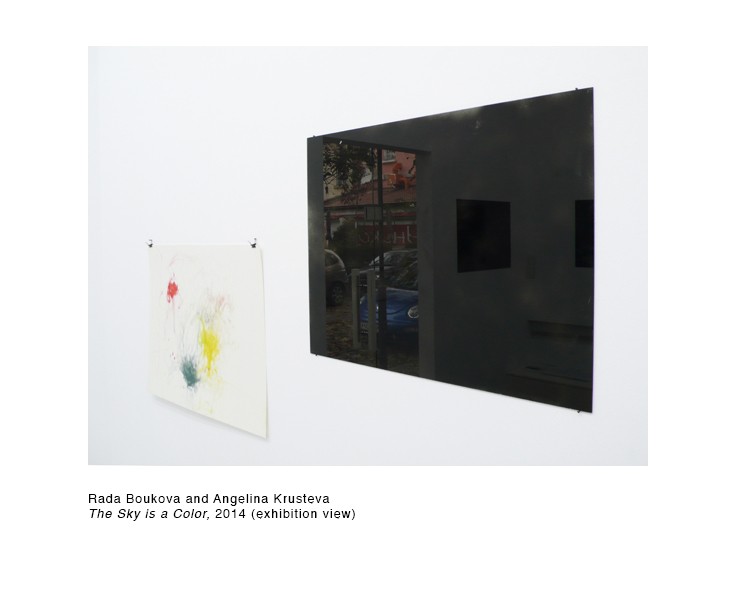

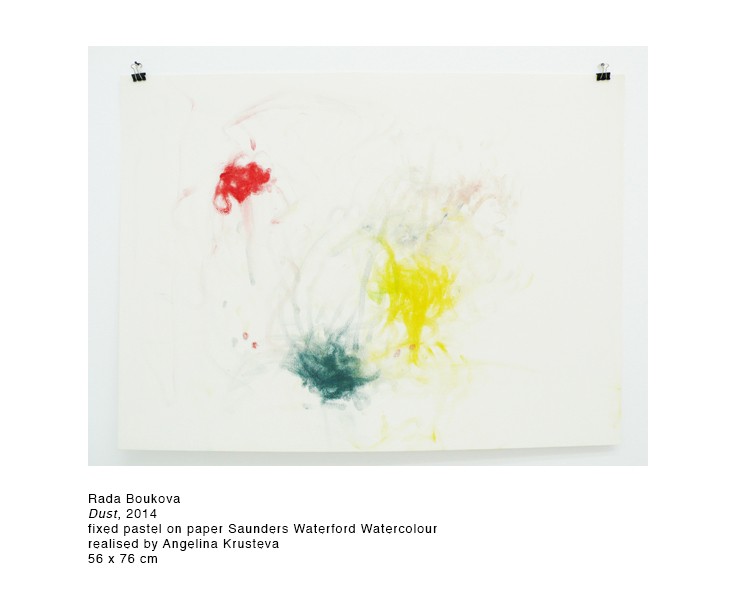

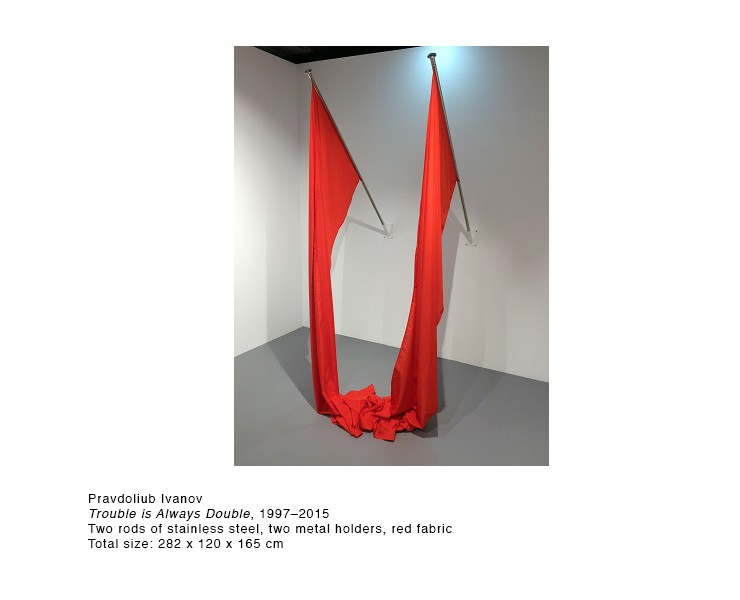

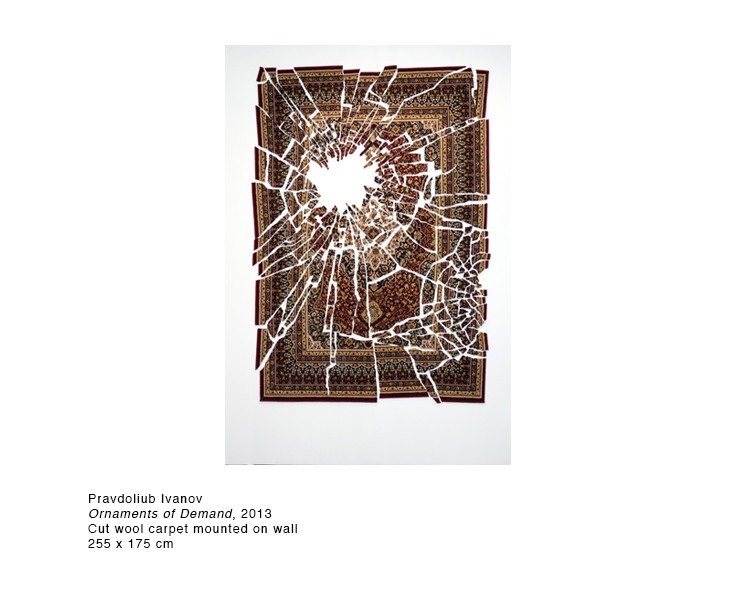

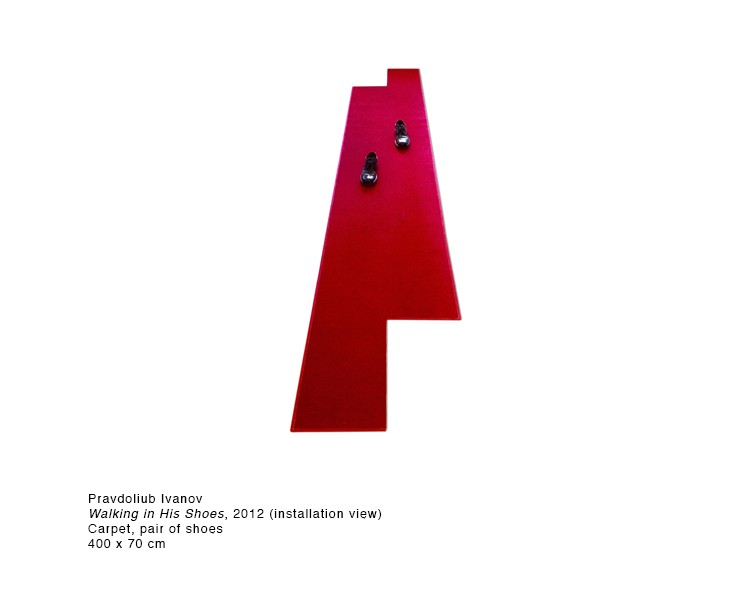

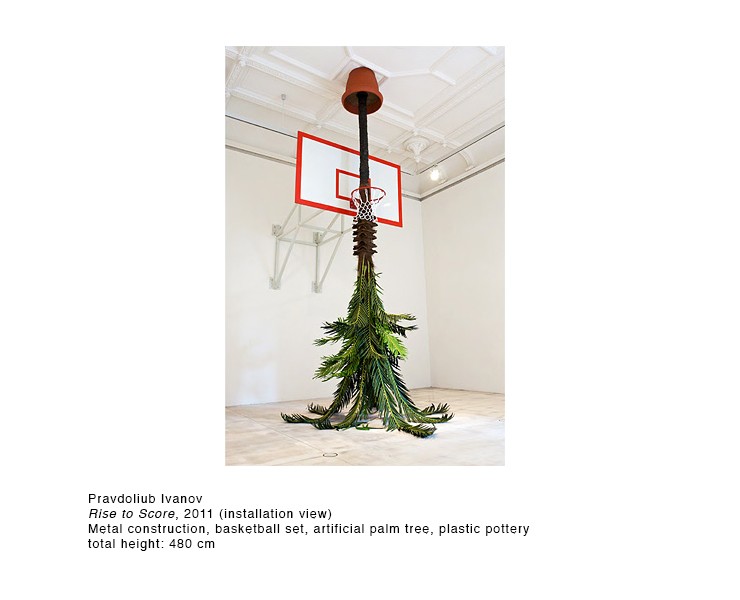

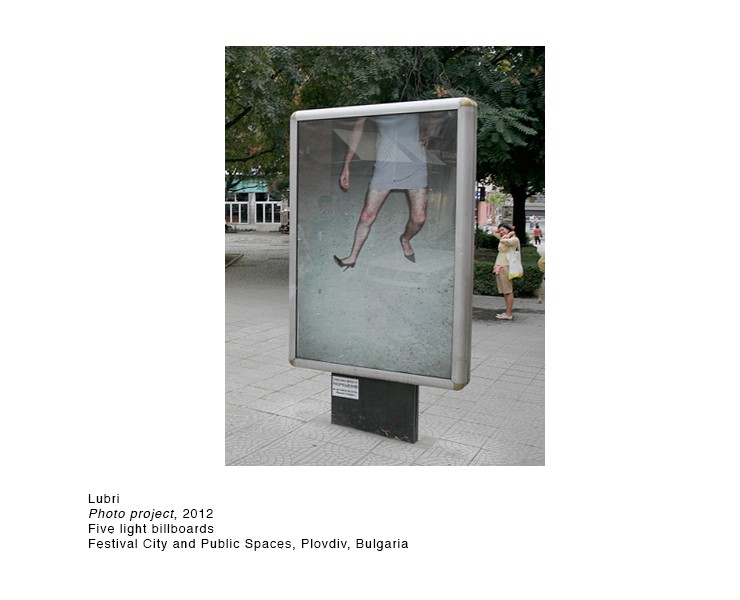

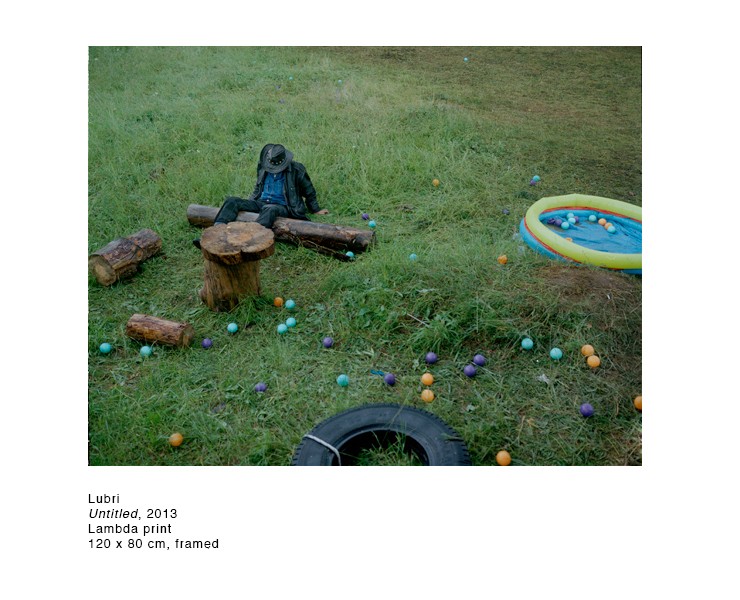

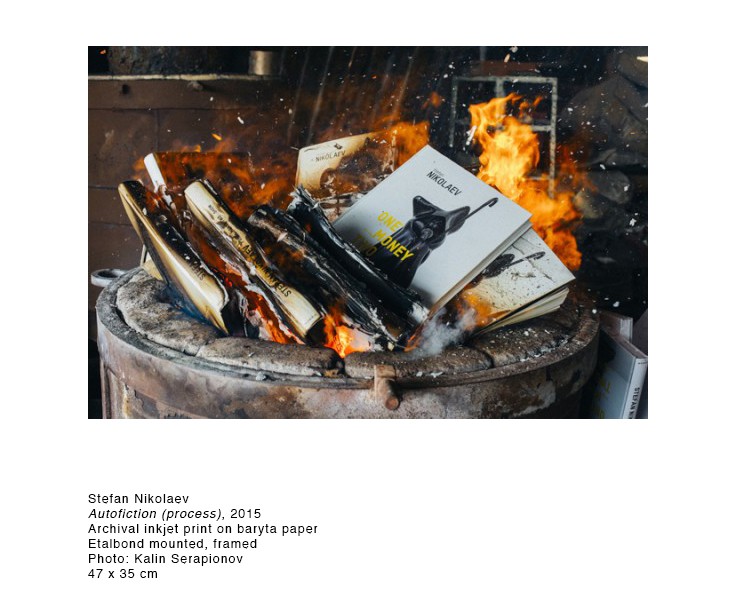

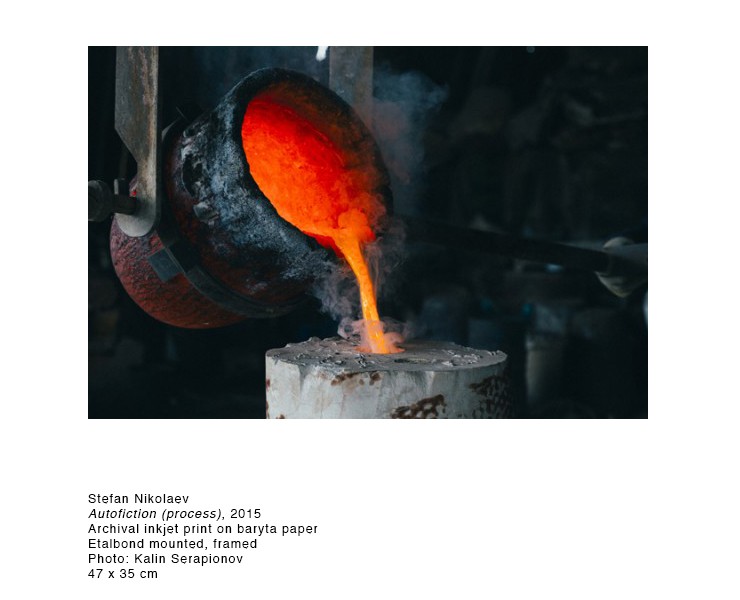

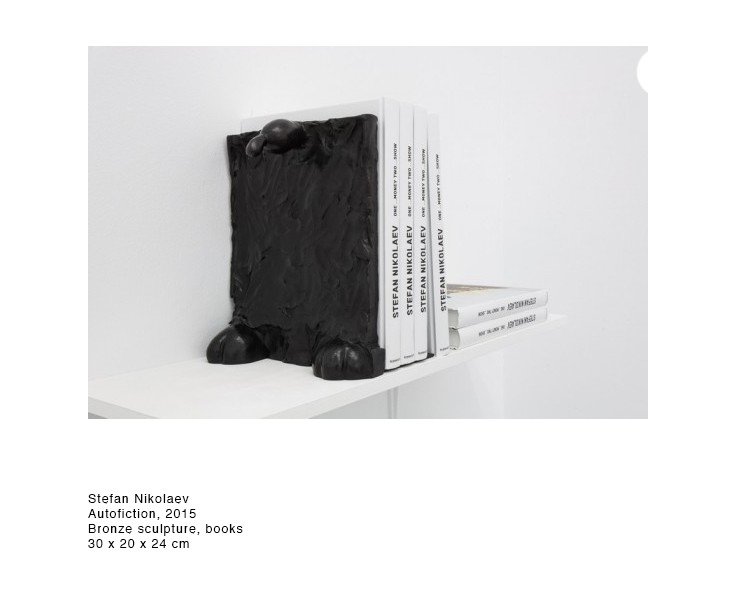

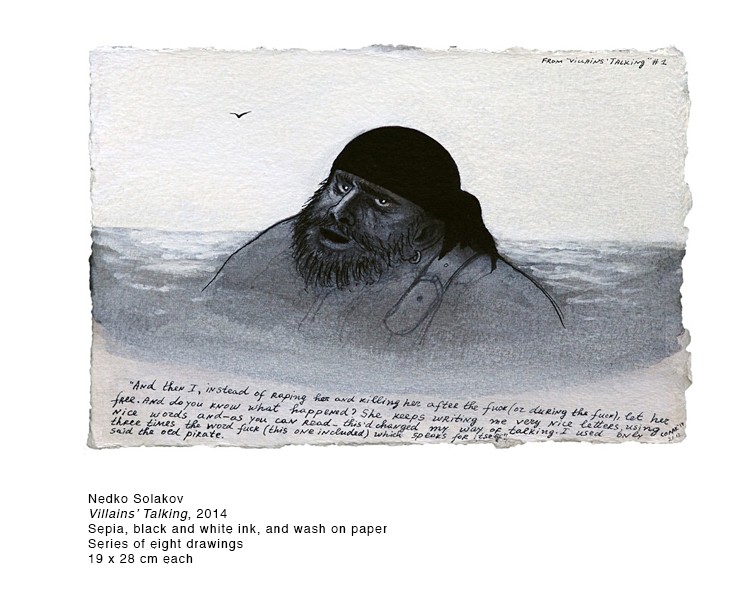

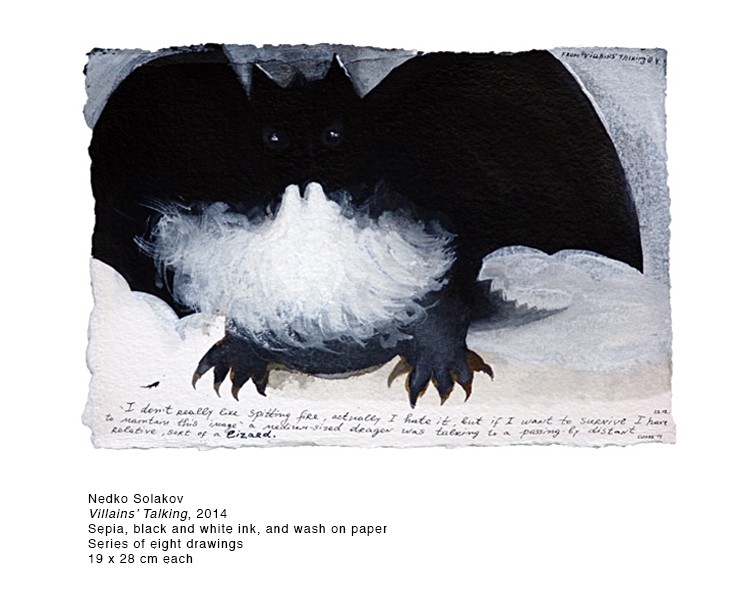

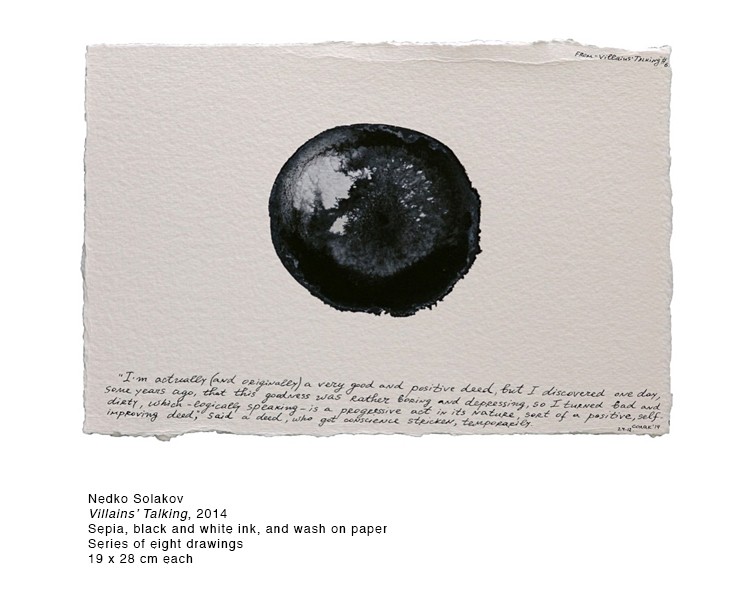

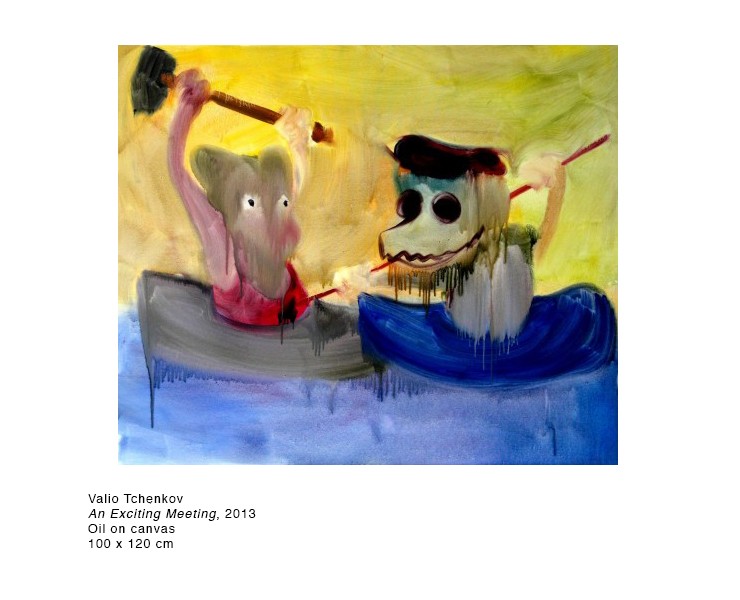

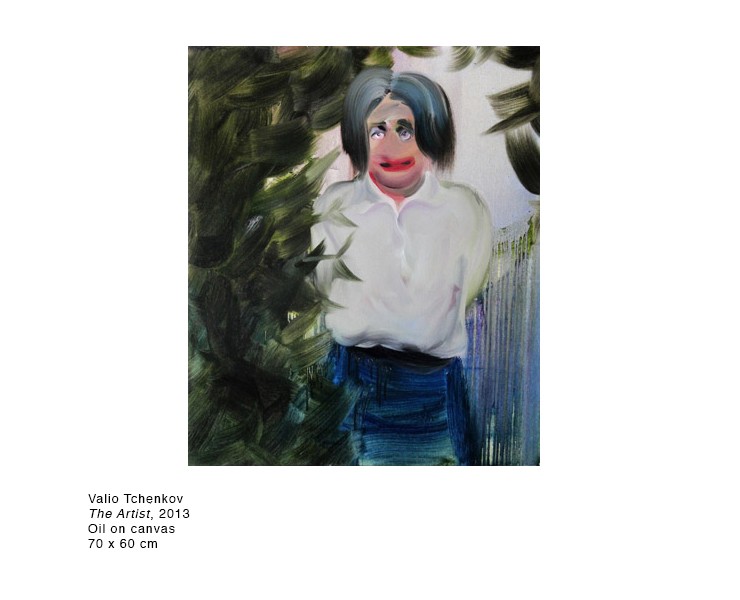

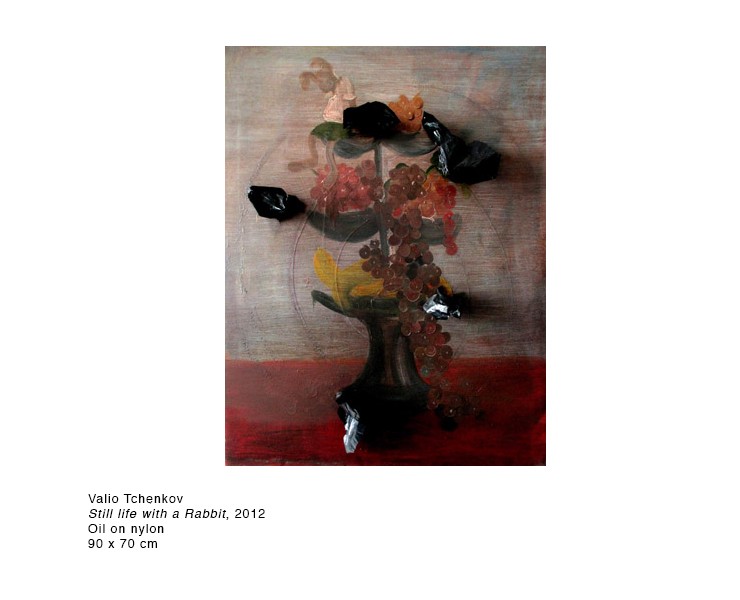

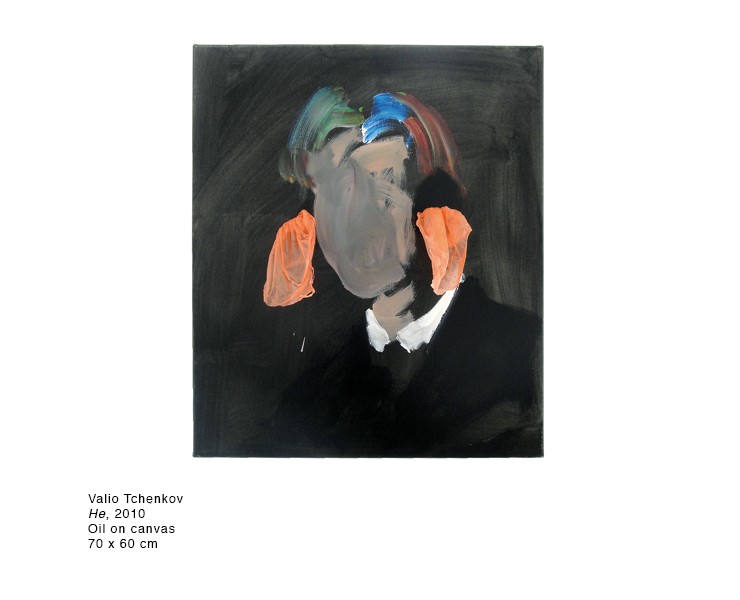

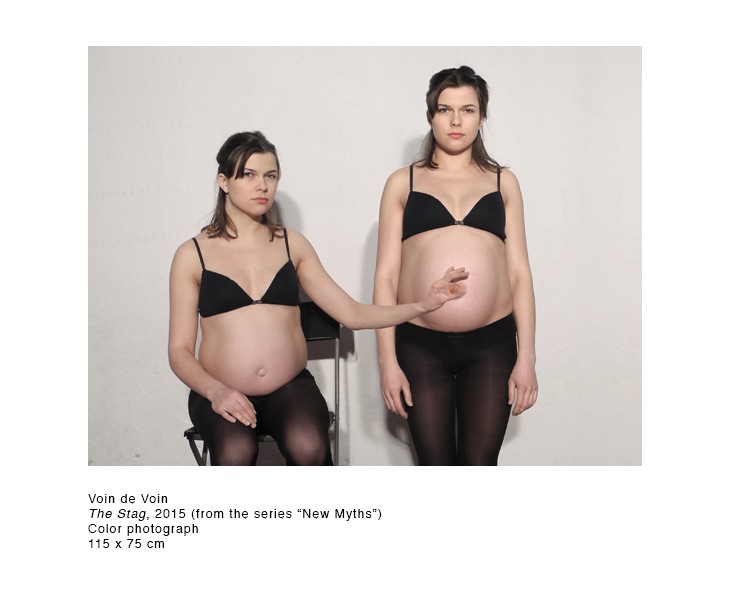

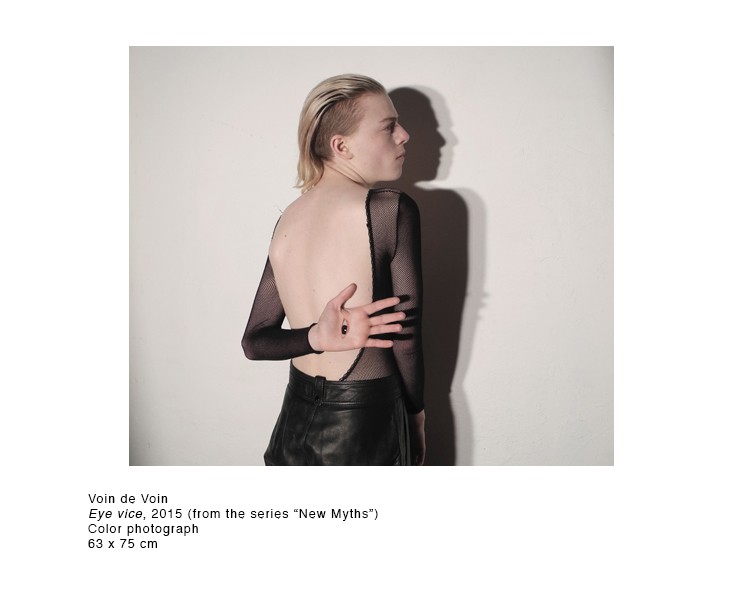

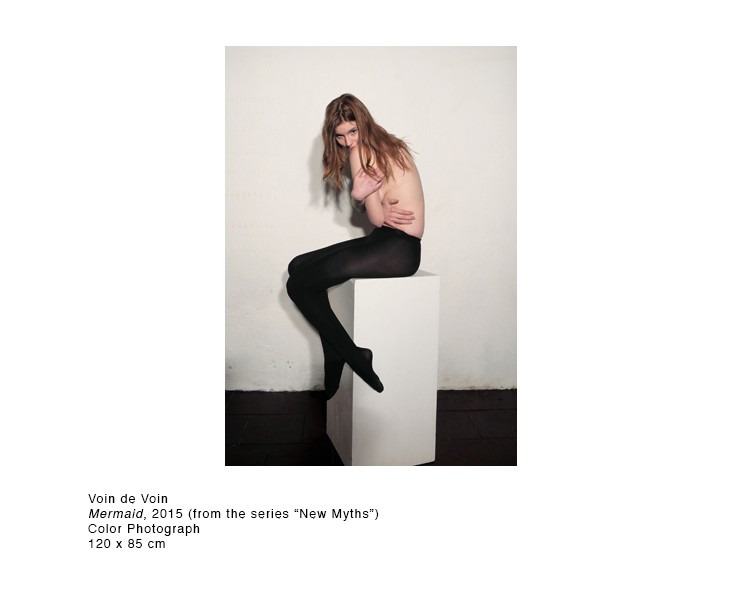

Today the gallery represents ten Bulgarian-born artists and features collaborations with international artists and curators. The works presented below survey some of the diverse subject matter and media engaged by the gallery’s artists. For her 2014–2015 exhibition The Sky is a Color, Rada Boukova collaborated with sight-impaired Angelina Krusteva, asking her to make drawings while Boukova made paintings inspired by her visualization of darkness. Pravdoliub Ivanov’s installations engage with global issues of hegemony and cultural appropriation, while the public and photographic works made by Lubri examine culture’s assumptions about and acceptance of images. Questioning ideas of recycling and self-mythologizing, Stefan Nikolaev burned copies of his exhibition monograph and used the energy created to produce bronze bookends that hold up the same monograph. Nedko Solakov’s darkly funny combination of image and text attempts to humanize villains while acknowledging their barbarism. Valio Tchenkov uses humor to merge conflicting emotions in his paintings and titles, creating charged visual spaces. In the series “New Myths,” Voin de Voin reconfigures ancient mythological symbolism in stark contemporary portraits.

The efforts of Vesselina and Katrin Sarieva to continue the development and exposure of Bulgarian culture locally and abroad are as tireless as they are admirable. Especially as institutions like MoMA continue to conspicuously overlook Bulgarian artists, I hope this brief dip into the country’s rich, innovative arts scene inspires readers to look beyond the white walls of New York galleries to find the dynamic work saturating cities like Plovdiv.

—Amelia Rina, Arts Editor