The power of images, from Monet to the moon.

Every book has its own texture, materiality, and topography. This is not only metaphorical; the process of creating a novel produces all sorts of flotsam–notes, sketches, research, drafts–and sifting through this detritus can provide insight both into the architecture of a work and into the practice of writing. Blunderbuss is excited to run this series, in which we ask writers to select and assemble the traces of a book in a way that they find meaningful and revealing. In this installment, Nick Mirzoeff reflects on the visual artifacts behind his latest volume How to See the World: An Introduction to Images, from Self-Portraits to Selfies, Maps to Movies, and More, released today in the U.S. by Basic Books.

In How to See the World, Mirzoeff draws on art history, sociology, semiotics, and everyday experience to analyze the history of images, from Velázquez’s Las Meninas to astronaut selfies. In our age of “visual activism,” in which the production and circulation of images help to drive social change, Mirzoeff offers an guidebook that is at once accessible and powerful. “Magisterial in scope and perspicuous in style” (W.J.T. Mitchell), How to See the World “solidifies [the author’s] reputation as a rangy, innovative theorist of visual culture” (Jack Halberstam).

–The Eds.

Before there was a book, before there was a project even, there was an intense anxiety of influence. The young editor at Pelican casually suggested that I pitch a book on visual culture because forty years ago they had published John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. As if an editor were to say: “What about another novel about a day in Dublin? Just updated?”

As I began to write, I was faced with the disorder of my archives. I work by associating images. I collect them. From social media, galleries, billboards, urban encounters. I have what seem like thousands of drives of all kinds but I can never find the one I want at any given moment. The process relies on my memory, which is awful for names, but tenacious of pictures.

Completely stuck, I drifted online. People were laughing it up about astronaut Aki Hoshide’s space selfie.

Image credit: Expedition 32 Crew, International Space Station, NASA.

Image credit: Expedition 32 Crew, International Space Station, NASA.

To many, it seemed absurd that Hoshide had ignored the chance to photograph the Earth below him. What he had made, though, was a compelling image that isn’t a selfie—a word that was just coming into use then—because we can’t see him at all. The reflection of the Earth in his visor recalled at once “Blue Marble,” the photograph of the planet from space, which is the most reproduced photograph ever taken.

Image credit: Apollo 17 Crew, NASA.

Image credit: Apollo 17 Crew, NASA.

This instant visual cliché first appeared in 1973, the year of Berger’s book, taken by the crew of Apollo 17. And there it was, a journey to map out from the first time that we could actually see the world to a moment only 40 years later where it wasn’t worth looking at.

A little research soon turned up “Blue Marble 2012,” which, in turn, is said to be the most downloaded photograph ever on Flickr.

Image Credit: NASA/NOAA/GSFC/Suomi NPP/VIIRS/Norman Kuring.

Image Credit: NASA/NOAA/GSFC/Suomi NPP/VIIRS/Norman Kuring.

It is shinier than its older sibling and carefully focused on the United States, rather than Africa. And it’s not a photograph. It’s a composite assembled from a variety of satellite images and then color-coded. The double displacement of “Blue Marble” in 2012 by NASA and Hoshide seemed to say the world itself has changed.

Looking again at Hoshide’s photo, I saw more anxiety than millennial narcissism—he was 43 when he took it anyway. I researched visors like his and discovered that they have been developed as militarized screens for fighter pilots. These days, looks really do kill. The helmet follows where the pilot is looking so that the weapons are targeted through the gaze alone. Like Hoshide, the pilot becomes invisible in his all-powerful display. Visualized war became another chapter.

Had Hoshide looked down, he might have seen one of the giant smog clouds over Indonesia or Beijing that are now said to be visible from space. I began wondering why there are no celebrated images of climate disaster—hurricanes and floods are usually still filed under natural disaster.

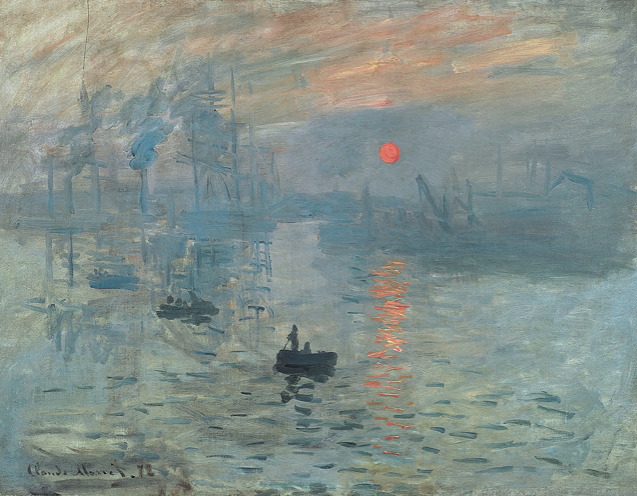

An exercise I used to play as a young art history grad student came to mind. I would patrol museums and exhibitions on the look out for smoke stacks in 19th-century paintings. As a then somewhat doctrinaire Marxist, I found these depictions praiseworthy as signs of industrial modernity.

Claude Monet, Impression: Sun Rising. 1872. Paris: musée Marmottan. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Claude Monet, Impression: Sun Rising. 1872. Paris: musée Marmottan. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Twenty-five years later, it was time for another look. Monet’s legendary Impression is perhaps the most taught painting ever. From a point of view informed by climate change, the yellow tinge of the painting became visible as coal smoke pollution. The legendary colors appeared as morning light refracted by coal dust into new luminosity. We don’t see climate change, I realized, because we have already absorbed it as the modern idea of beauty.

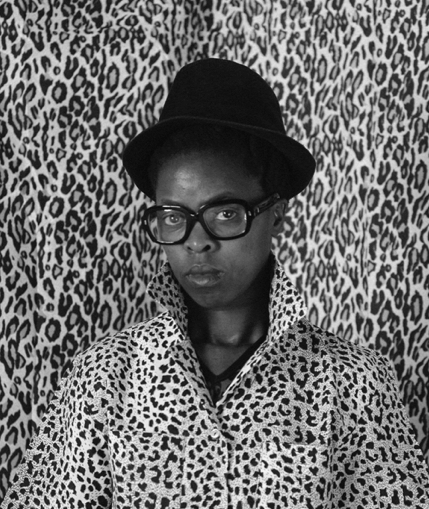

But it’s not all doom and gloom. As I was finishing that chapter, I went to an artist’s talk by the South African photographer Zanele Muholi. She identifies as a Black lesbian and she pointed out that she enjoys perfect legal protection in theory under the South African constitution. In reality, though, LGBT people face violence on a daily basis in the townships where most Black people live. She uses her work as what she calls “visual activism” to make her communities visible to themselves and to others.

These are the kind of pictures that might seem intrusive if taken by outsiders, imposing what specialists like to call the “gaze.” Muholi’s work isn’t like that at all. Her portraits show closeness, not distance; love, not voyeurism. Pictures like this can make change, not just depict it.

Zanele Muholi, Self-Portrait. Courtesy of the artist.

Zanele Muholi, Self-Portrait. Courtesy of the artist.

Not all of us can be famous artists. But maybe visual activism can be something we can all do in some ways. The ‘WeArethe99%’ Tumblr spread the message of Occupy Wall Street in 2011. Cell-phone video and photos have been essential to the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Since 2008, we’ve replaced ‘Hope’ with ‘the night is dark and full of terrors.’ So when the young Egyptian activist Ahmed says in The Square (2013), ‘as long as there’s a camera, the revolution will continue,’ I don’t care if it’s naïve. I need to think there’s some chance that it’s true so that I can go on.

______________

Featured image by Hayley Thornton-Kennedy.