Manhattan has pushed its undesirables to the tiny islands that surround it. Last fall, Jessica Feldman brought them back home.

Artist, activist, scholar. Outsiders may see three Jessica Feldmans, but she sees just one. “In my head they’re totally integrated,” she told me when we caught up at the Max Caffé near the Columbia University campus back in December. “It’s just that, in the world, they’re not.” Feldman’s areas of practice—intermedia art, organizing for the Occupy Movement, and analyzing the relationship between violence and discourse as a doctoral student at NYU—are all motivated by the ambition to collapse the distance between the worlds we imagine, the things we perceive, and the life we experience day-to-day. The Glass Sea, displayed in a Lower Manhattan park for two months last year, was a project in empathy. Through bricks, plexiglass, and projected images, Feldman translated the confinement experienced by prisoners and mental patients into an experience one could literally step into on the way to work or in between visits to trendy boutiques. Listening to her discuss her work—citing academic texts as her face betrayed palpable emotion on behalf of the incarcerated—it wasn’t hard to understand why she understands all of her roles as interconnected, even congruent. For Jessica, the separations between different styles of interpretation and expression (or between institutionalized people and the rest of us) are not immutable or impenetrable. They’re obstacles to be passionately resisted and creatively circumvented.

~Travis Mushett

BLUNDERBUSS MAGAZINE: How did the The Glass Sea come into being?

JESSICA FELDMAN: The project started a couple years ago—I guess it was 2010—and what happened was I was reading [French historian Michel Foucault’s] Madness and Civilization at the same time I had this residency on Governors Island from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. They have these artists’ studios in one of the old military buildings over there. I was reading about the history of expulsion and confinement and how madness got defined. And as I was doing that, I’m taking this ferry across the river everyday to go to my studio, in this little island that’s right near Manhattan, but it’s this totally different world. So I was kind of putting the two things together. One thing Foucault talks about at the very beginning is Ships of Fools, which is—you’ve read it, right?

BbMag: It’s been a while. [Ed. Note: Though he occasionally pretends otherwise, Travis has never read this book.]

JF: He talks about these Ships of Fools which were how they dealt with the insane way, way back, like pre-Enlightenment. They’d just put people on boats and send them off and hope they’d land somewhere in some other country. I was thinking about how water is used to construct spaces of expulsion and isolation and I was also noticing—in terms of the psychogeography of Manhattan—how these tiny islands surrounding our island have been used historically and currently for medical, psychiatric, and criminal institutions.

So there is Rikers Island, the jail, and Roosevelt Island which has two state-run hospitals that are, as far as I can tell from having been there, mostly filled with people who are permanently ill in someway or crippled. And then there are Randall’s and Wards Islands which used to be tuberculosis wards but now house Kirby Forensic and Manhattan Psych, which are two psychiatric hospitals, one for the criminally insane and one for the “regularly” insane.

I was thinking about this and about communication and isolation. Governors Island was, among other things, a prison for military deserters. It was a really ironic place to have a residency because I had to go out there and make art under duress. I was thinking about how artists end up getting pushed farther and farther out into the periphery all the time, too, and that we’re somehow deviant in our roles. I thought it would be really interesting if I could facilitate communication among these islands in some way. I wanted to try to have some sort of livestreaming thing where I could call up people in prison and it would be broadcasted into my studio. That was impossible. [Laughs]

BbMag: I imagine the prisons wouldn’t be too keen on that.

JF: The prisons wouldn’t be keen on working with me. Neither would the hospitals. But there are phones that you can call in these places. It’s just that the infrastructure itself is so dysfunctional. It’s not even the rules as much as it is that there’s no cell phone service on Governors Island, or there’s one payphone in the entire ward on Roosevelt Island for like 50 guys and you have to call a million times to get through. It’s sort of like isolation by default.

I ended up going to visit people who had been or were in these institutions and just talking to them. I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted until I had this long conversation with a guy who was interned on Roosevelt Island and was just asking about his life. What he gave me was a really, really regimented schedule of his day. And this is something that kept coming up. Schedules and regimens were important. It was a way of keeping track of oneself. I talked to these people who had days that are very structured in some ways and very empty in a lot of ways.

BbMag: How did you translate those experiences of current and former patients or inmates into something that could be communicated?

There is a big problem about empathy and sympathy when you think about these lives because, I can leave at the end of the day, right? I can just get back on the boat and have a nice dinner with one of my friends. So when I try to imagine what it’s like to be among the isolated, I can’t really imagine it.

I made a video using this little handheld camera shooting from my perspective and performing each of their days. I would wake up in the morning, smoke a cigarette, read the Bible, trying to go through their lives.

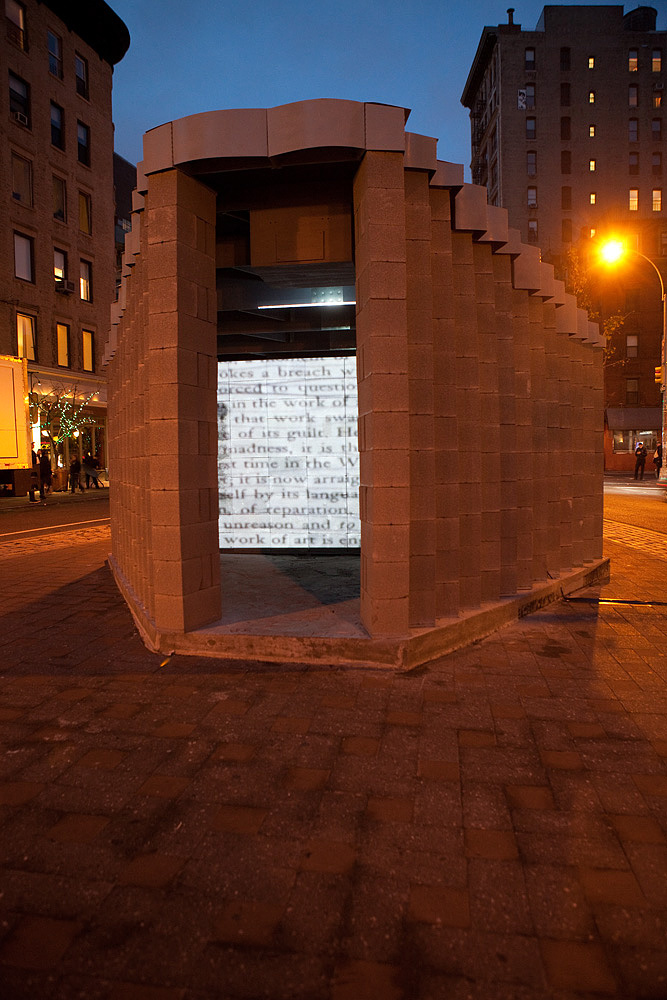

It was really hard and it was really depressing. But that footage became the video that this piece was centered around, that footage and those schedules. When I needed a place to put the video. I decided to build a prison cell. So I built a little brick room during my residency and that whole process was super hard. I just developed this very, very deep respect for gravity and masonry. I thought, “What the hell, I’ll just build a brick wall.” It’s not so easy to build a brick wall, turns out.

BbMag: And the name—The Glass Sea—is so evocative. Is there a story behind it?

JF: When I was on Governors Island, we got a tour of the island from one of the park rangers who works there. Really nice and knowledgeable guy, though I think his French isn’t very good. He was showing us around and there’s this fort on the top of a hill. Halfway up the hill there’s this sudden deep, dry moat before the hill continues to the wall of the fort. That particular architecture was invented by the French. It’s called la mer de glace, the sea of ice. I believe it’s named after this spot in the French Alps that is like that, a sudden chasm in the ice.

The purpose of this architecture in the military context is that it creates this layer of divide and perspectival power. So the fort is on top of the hill. The oncoming forces run up the hill, don’t see the drop, and fall into the dry moat and break their legs. So it’s this gulf that gives distance that you can’t really see or articulate or plan for, and it’s also this sense of perspectival power. So when we’re being given the tour, he interpreted it as “the glass sea” and I was like, this is the name of my piece. It’s so perfect.

The piece is about these chunks of water that exist to serve the same purpose. They separate people. They articulate—no, they do not articulate but enact spaces of separation and power. There’s a perspectival advantage for the state and for people who are in a position to describe someone as criminal, or as deviant, or as dysfunctional. But we don’t see it because we’re on the other side of the moat.

BbMag: How did this project go from your studio on Governors Island to a park in SoHo?

JF: I applied for and got a grant from the New York State Council for the Arts to put this piece out in a public space somewhere. Fast forward a couple years and tons of bureaucratic hoops that we jumped through, and we got approval and a site where we could install it as a freestanding prison cell in the middle of Manhattan, at which point I realized I couldn’t actually build a building and not have it fall over. So I hooked up with this architect friend of mine who does a lot of work with artists—Steve Gertner—and he and I worked together and designed this structure. It is bigger than a prison cell, but it made a really good projection room. The materials and design are basically based on a warped version of a prison cell or a hospital room or a psychiatric room. They’re all very similar in a lot of ways. So we built this room and put it up in the middle of SoHo. We made the roof from mirror-backed plexiglass. It’s sort of talking about [Foucault’s concept of] the panopticon and surveillance. It’s very similar to the materials used in surveillance.

BbMag: Like the domes put around security cameras?

BbMag: Like the domes put around security cameras?

JF: Yeah, but it’s looking at the sky. From inside it’s just dark, but from outside there’s the domed mirrored roof that reflects the sky, so as you’re approaching it, you can see the sky angling up. It’s this gorgeous expansive thing, but when you go inside, it’s dark and confined. There was a video running on a loop and it was also presented with signs for each of the schedules that were narrated to me. The video is kind of oblique, like “Oh, someone’s reading the Bible.” It really is sort of meditative and boring and slow, and looking at the wall, looking at the ceiling, looking out the window. But if you put that together with these schedules it takes on this whole level of gravitas.

BbMag: I’d imagine slow, meditative, and boring is probably similar to the experience of being in prison. Maybe punctuated with terror.

JF: It sounds that way. The terror wasn’t talked about as much in the interviews I did, but I think it’s in there. The thing that really struck me was that one of the guys I was talking to told me about the jobs you can do in prison, and he was like, “Well, the most highly paid job is suicide aide.” That’s what he said the job was named, which makes it sound like you’re helping someone kill themselves–but apparently it’s the opposite. They pay all these guys to go from cell to cell and make sure no one is trying to hang themselves. It doesn’t quite work because the amount of time it takes them to cycle through the cells is longer than the amount of time it takes to die from strangulation. Sometimes I guess they can catch it and sometimes they can’t. They’re paid 30 cents an hour. That one really hit me hard. Suicide was a recurring theme. The guy I talked to on Roosevelt Island, he talked a lot about trying to keep track of himself and knowing that he was alive.

BbMag: You described navigating the politics of getting this into a public space as tricky—

BbMag: You described navigating the politics of getting this into a public space as tricky—

JF: Oh my god.

BbMag: I was curious that since this project has something of a subversive message, if that made it more difficult to get it approved.

JF: Yes. Part of what happened is that when we described the project, part of the message was left out. Let me be careful how I say it since this is going to be published and also because the implicit meaning in the piece is powerful and offensive and uncomfortable. We didn’t say that much about it when we were applying to put it up. We said, “This piece draws correlations between the lives of people on Randall’s, Rikers and Roosevelt Islands and discusses the relationship between mental illness, being incarcerated, and the psychogeography of these islands.” And that’s enough. [Laughs] That’s already a big controversial question, but it wasn’t like, “This piece criticizes the Prison-Industrial Complex” even though it does. But I wasn’t going to say that.

I don’t know everything that went down, but I know it took a while to get through. Some of it was just like needing to be approved by a structural engineer.

BbMag: How was the piece, and its politics, received afterwards?

JF: What was really interesting was that, after it was installed, one of the Italian-American community groups in the area got very offended. It was in this spot right next to a park named after an Italian-American police officer. It was sort of a two-pronged offensive. On the one hand they were upset because it was disrespectful to the legacy of this police officer, and on the other hand they were upset because they thought it was suggesting all Italians are criminals. I think they were just upset and didn’t want a prison cell next to their park.

We ended up explaining that this is not targeted toward Italian-Americans, that it’s talking about questions of confinement and empathy. But to me, the piece was already doing its work. If all I’m doing is taking something that exists in another space and putting it here, I’m actually not putting in any language about whether it’s good or bad to be a criminal, I’m not putting in any language about how corrupt or not corrupt the police are or the Prison-Industrial Complex is, or the continuum between illness and criminality and what gets called deviant and what doesn’t. All of those questions are in the piece but they’re…

BbMag: Implicit rather than explicit.

JF: Yeah, but just the gesture of putting this thing there was incredibly offensive to some people. They didn’t want to see it.

BbMag: It kind of seems like they got the point.

JF: Right. If you don’t want to see this, I think that means you need to really look at it. Or at least that’s what I’m trying to do with the piece. It was a little threatening because they wanted to picket the installation and protest, and they sent around a petition against the piece.

BbMag: It was good publicity, though, right?

JF: It was, but it actually did affect how long we were able to leave it up. I know that maybe the Commissioner of Corrections wasn’t very happy with it. There were some Deputy Mayors who were concerned, and I don’t know how much that had to do with the content of the piece and how much it had to do with the reaction of this community, but I was told that we couldn’t leave it up longer because people were getting antsy. So we took it down.

Fortunately, The Man hasn’t taken down all of Jessica Feldman’s public art. If you’re in the New York area, check out her piece Obol, running at the Socrates Sculpture Park through this Sunday March 31st. Also, be sure to give a look to her freshly renovated website,

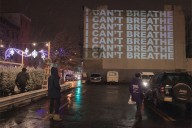

Header Photo: Jessica Feldman’s The Glass Sea, constructed with architectural designer Steven Gertner, on display in the SoHo neighborhood of Manhattan.

All photos by Arthur Moeller.