Soft pants, sweet pups, and the making of a hypnotic debut.

Every book has its own texture, materiality, and topography. This is not only metaphorical; the process of creating a novel produces all sorts of flotsam–notes, sketches, research, drafts–and sifting through this detritus can provide insight both into the architecture of a work and into the practice of writing. Blunderbuss is excited to run this series, in which we ask writers to select and assemble the artifacts of a book in a way that they find meaningful and revealing. In this installment, Tracy O’Neill shares the soft pants and goddamn multiplication tables that helped her write The Hopeful, released in June by Ig Publishing.

In The Hopeful, 16-year-old figure skating prodigy Ali Doyle feels her Olympic dreams shatter along with of her two vertebrate. When she finds herself addicted to amphetamines, however, something more than a gold medal might be on the line. This debut novel has been described as “hypnotic” (KarolinaWaclawiak) and “brilliant and bold” (Julia Fierro), and earned O’Neill a spot on the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 list.

–The Eds.

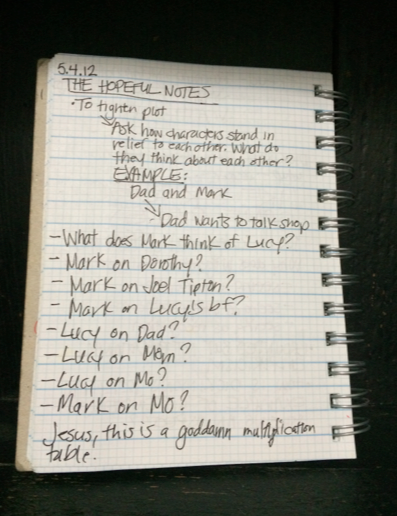

You know how some people say that writing is revising? Well, I can say with certainty that most of my work on The Hopeful was, indeed, revision. This is mostly because I had no idea what “narrative structure” was. On the first draft, I would do things like think about how to write a single sentence for three hours but not do things like ask what the shape of the novel was. Consequently, I ended up revising more times than I can remember. I’d assign myself tasks that sometimes occasioned commentary, such as the remark below, “Jesus, this is a goddamn multiplication table.” In fact, I later followed through on those notes and made a matrix of characters’ positions on each other. This helped knit together the satellite figures so that they didn’t exist in vacuums.

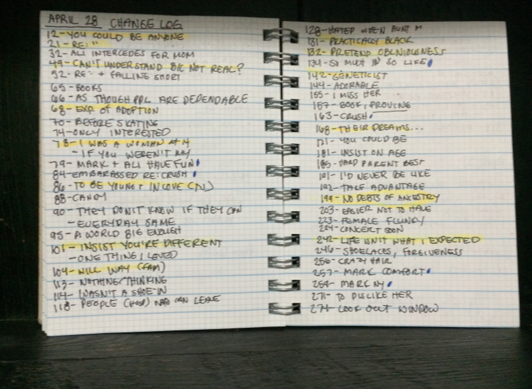

During an initial revision, I somehow failed to grasp that all sections of text are not fungible. As such, I’d find holes and inconsistencies in the text. It wasn’t cute. Ali, the narrator, hadn’t yet met her drug dealer but was somehow popping pills. Mark, her tutor, hadn’t yet told her about the Defenestration of Prague, but there she was inexplicably riffing on windows. And there’s nothing less funny than a window joke removed of context. After writing myself a berating little screed, I used the “Compare Documents” function in Word, then jotted out a log of every change I’d made. The highlighted changes were new additions, not textual permutations.

Because the book’s protagonist is an ex-figure skater, I decided to weave in the history of the Tara Lipinski-Michelle Kwan rivalry. It was important that Ali describe these sporting events through a lover’s eyes, attending to the details the way one might notice the slope of a beloved nose. To write these passages, I watched footage of the events, thinking always of Elizabeth Bishop’s “a gesture/I love.” For Ali, these events would be parcels of loved gestures.

When I was writing The Hopeful, I was working in nightlife. I determined that the disciplined thing to do was maintain the club schedule all week, staying up until at least four in the morning so that I wouldn’t tire during my shifts. A lot of friends, not for the first or last time, thought I was making an incredibly stupid decision. But it was great for writing. I’d work on the book on my nights off, very hopped up on caffeine. The beauty of night writing is that you cannot be distracted by business hours chores like going to the bank or grocery shopping. You fill the dark and silence with words. Each night, I’d make a pot of coffee, then drink from this huge mug whose capacity meant less time wasted refilling.

Besides the big ass mug of coffee, I have another requirement for writing: soft pants. I cannot get work done wearing jeans. Denim conspires to make you aware of its texture at all times. So I have a drawer full of writing bottoms. Many of them have holes in exactly the same place in the butt from sitting. I call them my battle wounds.

Amidst the revisions, I adopted my dog Cowboy. He and I took the flâneur approach to novel writing, walking and observing the city. Sometimes, our jaunts didn’t glean solutions to craft problems; they just unscrewed my head. When you’re laboring over fiction, it’s easy to imbue the process with solipsistic urgency. But there is little as urgent as a half-trained puppy’s full bladder. I needed that sense of perspective.

______________

Featured image by Hayley Thornton-Kennedy.