On editing, El Greco, and finding the right wrong note.

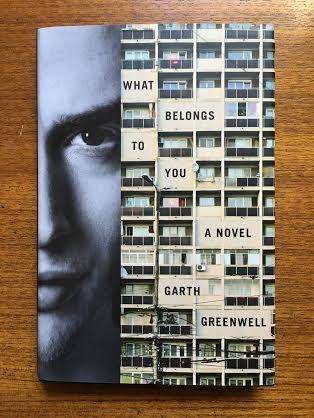

Every book has its own texture, materiality, and topography. This is not only metaphorical; the process of creating a novel produces all sorts of flotsam–notes, sketches, research, drafts–and sifting through this detritus can provide insight both into the architecture of a work and into the practice of writing. Blunderbuss is excited to run this series, in which we ask writers to select and assemble the artifacts of a book in a way that they find meaningful and revealing. In this installment, Garth Greenwell reflects on the summer he spent in Madrid revising his debut novel What Belongs to You, released last month by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

In What Belongs to You, an American teacher in Bulgaria finds himself ensnared in a torrid relationship with a young hustler. Their affair forces him to confront the shame he still carries from his childhood in the south, where his queer desires rendered him an outcast. This novel has already been lauded as a “masterpiece” (Edmund White) and a “rich, important debut, an instant classic to be savored by all lovers of serious fiction” (New York Times Book Review), and the New Yorker’s James Wood is already comparing Greenwell to Virginia Woolf and W.G. Sebald.

-The Eds.

I worked on edits for my novel, What Belongs to You, over two months one summer in a succession of rented apartments in Madrid. I was in Spain to be with my boyfriend, the poet Luis Muñoz, but his apartment was too small to contain all the misery I felt while I worked. I needed my own space.

Looking back, it’s very hard for me to understand why the process was so dramatic. My editor, Mitzi Angel, lavished attention and care on the manuscript. She worked by hand, sending me scans of the pages with her markings; a new batch would arrive every few days. As soon as I got pages, I found I couldn’t do anything but work on them, often for ten hours a day.

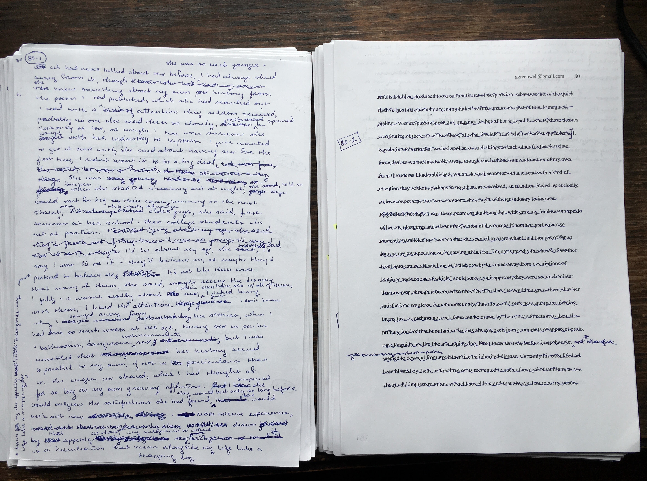

I worked by hand on a clean copy of the manuscript, with Mitzi’s marked copy on my iPad. All of the changes were at line level, none affected plot or structure, but they added up to a major edit: we cut 17,000 words from an 83,000-word manuscript. Sometimes entire passages were struck, sometimes whole pages; often there would be a note telling me to condense several paragraphs to one. Mitzi seldom suggested particular language to fix problems, but she was eagle-eyed in spotting them. Painfully often, in the margins I found the notation “not good enough,” or “this needs to be better.”

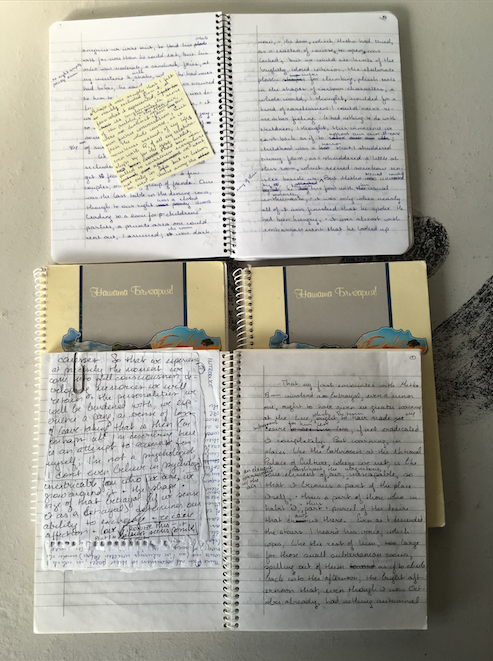

I wasn’t sure I could make it better, and as we inched our way forward I felt I was losing my ability to make my own judgments, or my ability to see the manuscript at all. As I worked through each page I laid it face down, using the overleaf for rewrites, adding scraps and post-its as necessary. But slowly, revision came to feel more and more like composition, and the manuscript came to resemble the notebooks in which I wrote the first draft of the novel. The book, sections of which I had finished years before, became alive for me again.

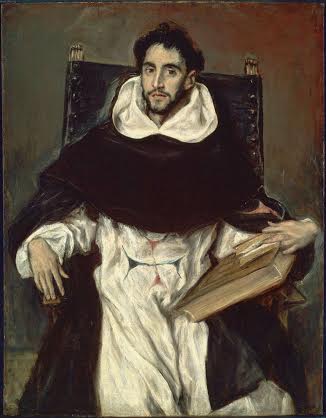

I hardly saw Madrid at all that summer. I met Luis for dinner every evening, but my days were solitary. When I couldn’t bear to edit anymore, I walked the relatively short distance from my apartment on the Calle de las Huertas to the Prado. I have a difficult relationship to museums, which overwhelm me, and to visual art, which I know shamefully little about; all my education in the arts has been literary and musical. But that summer there was an extraordinary exhibition of El Greco, and I found that almost the only time the anxiety of editing fell away was when I stood or sat in front of one of his paintings, always only one per visit.

I’m drawn to art in which things are a little askew. Straight realism isn’t very interesting to me; I like to see the interference of consciousness, the way perception is muddied by a unique interpreting mind. El Greco’s paintings are eccentric, strange, willful; I loved them. Standing in front of his Portrait of Fray Hortensio, I couldn’t help wondering what an editor would make of it: the obviously strange angle of the back of the chair, for instance, or the weird positioning of the hands. Wouldn’t an editor want to make those less strange, to straighten those things out? And yet wasn’t their strangeness the key to the greatness of the painting?

A favorite teacher of mine in music school, a composer, used to talk about the importance of the right wrong note, the eccentricity that both surprises and feels immediately inevitable. I’m suspicious of the arguments we make to justify our opinions about art, especially art we’ve made. I’m not particularly given to confidence in my judgment; I can justify anything, I sometimes think. Working on revisions to my novel, I found that I couldn’t judge the validity of my editor’s criticisms until I had worked through a new version of a passage. Only then, when I had done the work—I always resist work, I’m the laziest person I know—could I see the virtues and flaws of what I had made.

I remember feeling, in the most difficult moments, that I was losing authorship over my work, that I was compromising some distinctive element that made the book mine. But now that seems terribly silly. When I read the finished book, I can’t remember most of the passages we cut; I don’t doubt anymore that the book is stronger without them. I know that I’m reading a collaboration, a book that would be very different without the interventions of a brilliant editor. But it feels like my book, the book I wanted to write.