Every book has its own texture, materiality, and topography. This is not only metaphorical; the process of creating literature produces all sorts of flotsam–notes, sketches, research, drafts–and sifting through this detritus can provide insight both into the architecture of a work and into the practice of writing. Blunderbuss is excited to run this series, in which we ask writers to select and assemble the artifacts of a book in a way that they find meaningful and revealing. In this installment, Jay Deshpande discusses how Magritte, a woodchuck (!), and merciless edits contributed to the writing of Love the Stranger, published by YesYes Books.

The poems in Love the Stranger interrogate love and its elusiveness by invoking the erotic and the mysterious, the banal and the strange; Chet Baker, Jack Palance, Kim Kardashian, a golden beast lying in wait behind you. Out of his “intensifying linguistic gift,” Deshpande has written “a book of great beauty and of terrible suspicion regarding that beauty” (Josh Bell). Perhaps, Deshpande suggests, real intimacy, like a curving line of the Fontana di Trevi, is always moving away from us–but these poems will stay with you.

–The Eds.

Image

I’ve never thought of my intelligence as being a highly visual one: I’m not great with faces and I think more in terms of word and sound and rhythm than images. That said, this book was very much contoured by a set of visual influences. On the cover is a photograph of Antonym, a sculpture by Diana Al-Hadid. I first came across Al-Hadid’s work in a group show at MassMOCA in summer 2012. I was really beguiled by the architectural elements of her larger works, and how she incorporated a sense of time and ruin and implied narrative while still making the body highly sensual and evocative. I was still stewing on that first piece of hers I’d seen when, a few months later, Al-Hadid’s next show opened just down the street from where I was living in Chelsea. I felt sure her work was following me for a reason. It was there that I found Antonym. I love the combination of threat and intimacy in the piece, and how (especially at this angle) it serves as a sort of invitation to the viewer and the reader. Maybe.

One of the most importance influences on the poems in the book was Rene Magritte. Magritte appeals to my penchant for a kind of dream realism where an inherent logic exists just below the surface but is not pronounced. My friend the poet and translator E.C. Belli encouraged me in this respect, and Magritte started to be a springboard for generating new work. I was also fascinated by his titles—I’m interested in the relationships between the title and the content or body of a work of art. And both Al-Hadid and Magritte generate remarkable titles.

There’s a lot of ways to write the ekphrastic poem: you can immerse yourself in description of the artwork, you can leap off of it into interpretation, you can narrativize it and propagate a story…. My way into ekphrasis is to work through the title of the piece and see what comes out, especially if I can turn away from the actual artwork a little and hear a voice that emerges from it, a sort of lyric I that wants to speak tangentially. So I started writing poems off of Magritte’s paintings. For a while I had a whole set of them—often very short pieces, forming little puzzles. The paintings I wrote out of included The Threshold of Liberty, The Difficult Crossing, The Menaced Assassin —and also The Lovers.

The Lovers is the basis for a poem in the first section of my book. I’ve always loved what this painting does with eros and limit; early on it became a kind of tuning fork for my work in the book as a whole. I was also really inspired by the painting Homesickness. For a long time, Love the Stranger included a poem of mine with that title which worked as a sort of small hinge in the book. Late in the revision process it became clear to my editor and me that we could remove the poem and its presence would still be felt. A line of that poem then gave me the title for the last section of the book: “A Gold Beast Come to Rest Behind Me.”

Process

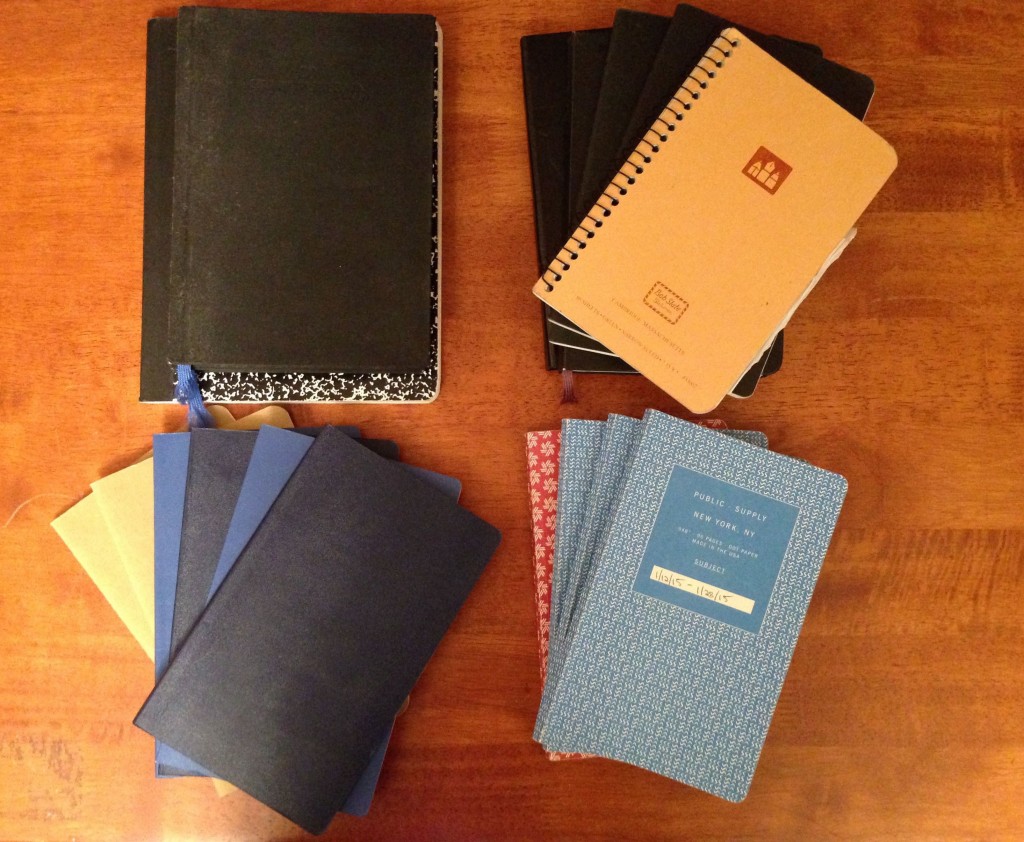

Here are some of my notebooks. I’m pretty journal-flexible, though I tend towards the 5 x 8-inch trim size, and I resist totally unlined pages. I’ve enjoyed using notebooks made by Public Supply. I kind of like having a range of sizes; I’m not a highly consistent person and my writing should reflect that. The variation definitely has informed how I write and what I go towards. I’m sure that the times when I’ve worked more in the prose poem than in verse has had something to do with the notebook atmosphere of the period.

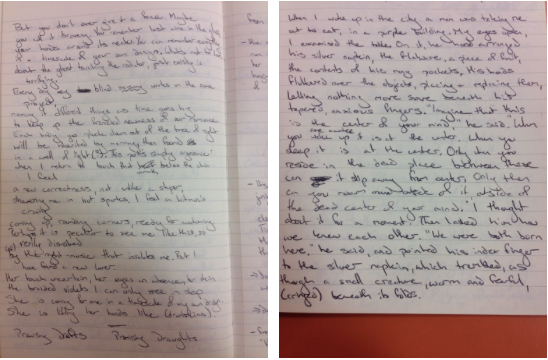

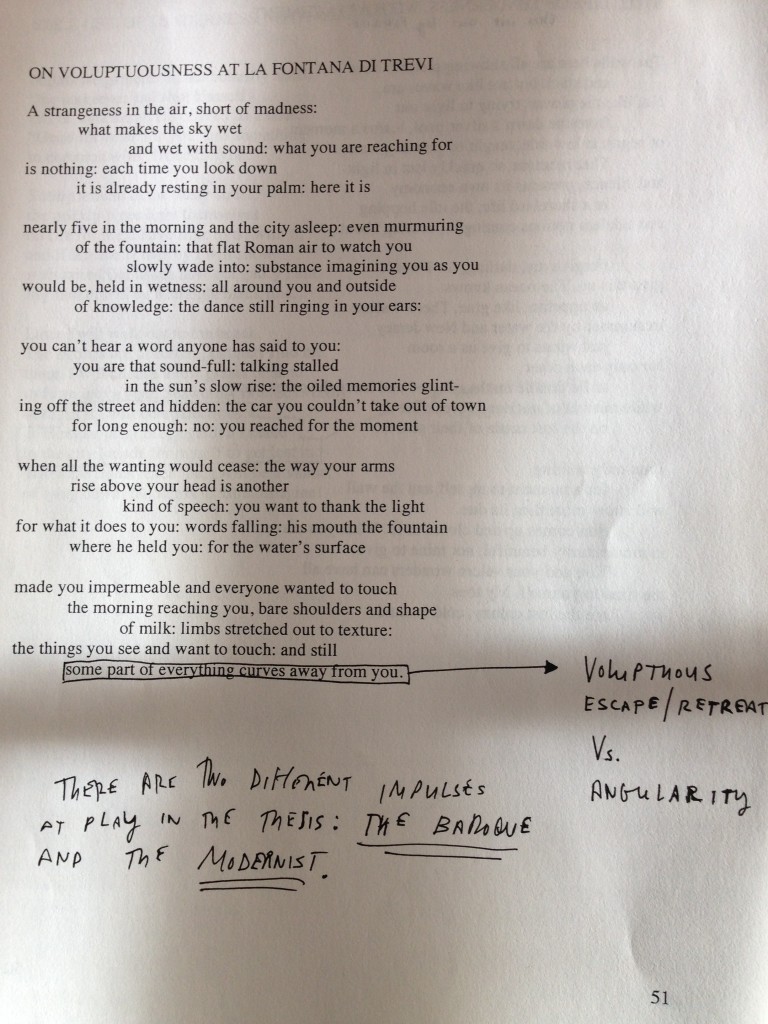

Some poems, like these two (“Reports of the Dream You’re Not Likely to Recover From” and “Threatening Weather”), came to me pretty whole. When I first drafted them, I could basically feel their shape. But there are at least a few that took awhile and then smacked me profoundly with their needed form. The best example is “On Voluptuousness at La Fontana di Trevi.” Here’s the version I brought into my thesis workshop:

These notes are from Kirkwood Adams; I think this was where I saw that everything the poem needed existed in that last utterance. So, painfully, thrillingly, I cut off all the rest:

ON VOLUPTUOUSNESS AT LA FONTANA DI TREVI

Some part of everything

curves away from you.

Place

I wrote Love the Stranger in a number of different locations over the course of the six years I’ve lived in New York City. But one of the most fertile places for me was the Saltonstall Arts Colony in Ithaca, NY. I had a residency there in summer 2013.

I lived in the basement of the main house and woke up every morning to wide light over the field, the sun warming everything. In wind the linden trees flickered. I ate well, watched “Battlestar Galactica,” drank Shiner Bock, chocolate milk. I made sure there was nothing for me to do but run and read and write. I also made some friends I wouldn’t find in NYC.

Ithaca helped me quiet the more extroverted parts of my mind. Each day I was able to dig in deeper to my work and generate more drafts. This was also the period when I set myself most seriously to the task of reading complete books of poems, each in a single sitting, and studying how they worked as total organisms. I stretched out during that month, pushing certain poems through dozens of versions and experimenting with other projects.

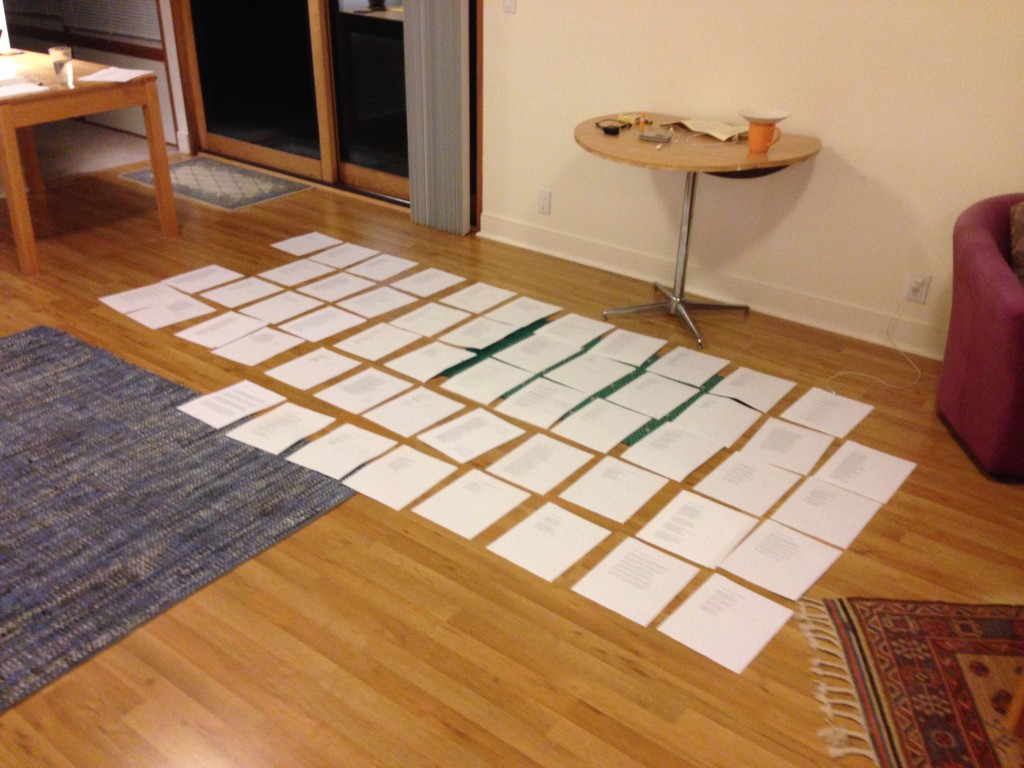

The trip yielded so much insight into my manuscript that as soon as my residency ended I resolved to come back. I returned for a week at Saltonstall in early November of that year. At this point the house was quiet and snow was beginning to fall. The blissful company of four other artists and the colony director was replaced by almost total silence. So I laid out everything I had and rebuilt my manuscript, one more time, into the form of this book. When I came back to Brooklyn, I took one last night to make revisions and then it was ready; I started to send it out.