Circumcision present. Circumcision past. Circumcision future?

Last year, a woman in South Florida spent nine days in jail for refusing to allow her son to be circumcised. The father of the child called circumcision “just the normal thing to do,” and the courts sided with him in the parents’ long running dispute over the matter. Forced to sign over consent for the circumcision in order to regain her freedom, the mother quickly became a martyr for the anti-circumcision movement. The image of her final surrender that circulated in the media – hands held together as she cried to the heavens – was the perfect postmodern rendering of saintly iconography, a fitting tribute to the religious fervor often expressed by those opposed to circumcision today.

Who are these anti-circumcision activists, and should we take them seriously? The answers to these questions require that we consider not just the foreskin, but the very foundations of contemporary social and psychic life.

Anti-circumcision activists call themselves “intactivists,” and try to combat what they perceive to be the widespread ignorance about male circumcision – a practice performed routinely on boys in America, as well as an important ritual for Jews and Muslims. Intactivists flood online discussions of circumcision (such as the comments page of relevant articles) with their views, often angrily and aggressively. Many set automatic Google alerts for keywords relating to circumcision, enabling them to respond first and set the parameters of the discussion. They typically argue that the Western opposition to what is commonly called “female genital mutilation” belies an unfair, even sexist, double standard. Male circumcision, they claim, is an analogous but much more commonplace mutilation, inflicting unnecessary pain, suffering, and lifelong trauma on countless men. Though intactivists primarily focus on the pain and alleged loss of sexual pleasure that circumcision entails, they have attributed nearly all the major physical, psychological, and social ills of our era to the procedure, including ADHD, autism, sexually transmitted disease, sudden infant death syndrome, PTSD, anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and – why not? – Islamic terrorism.

A fairly representative comment, taken from Reddit, reads, “The mutilation of a little boy’s genitals (also known as circumcision) is an act of barbarism that should be absolutely intolerable to any just and free society. Anyone partaking in this act should be tried in a court of law and put in prison for torturing children and violating their rights.” Responding to the apparent rise in anti-circumcision discourse, a Jewish a cappella group produced a tongue-in-cheek, pro-circumcision YouTube video, in which they sing, to the tune of the pop hit Royals, “Cause we’re gonna be Mohels/We’re not afraid of a little blood/Your man made law just ain’t for us/We serve a different kind of boss.” Beneath the video, an intactivist writes, “YOU FUCKING SCUM! YOU FUCKING RAPE APOLOGIST!”

Of course, intactivists are not only on the Internet. They have organized countless public demonstrations over the years, lobbied legislators, and in 2011 nearly succeeded in getting a measure that would criminalize circumcision onto a San Francisco ballot.

The style of intactivism often involves intensely personal testimonials of victimization, which, were intactivists not so serious, would seem to be a parody of contemporary identity politics. “Circumcised men,” writes the anthropologist Eric Silverman, “express, in the uniquely modern American practice of public confession, their intimate experiences with sexual dysfunction, poor relationships, and feelings of parental betrayal, violation, victimization, powerlessness, distrust, shame, abuse, deformity, and alienation.” Although the majority of circumcised men rarely complain about their lack of foreskin, intactivists generally consider the unenlightened to be suffering false consciousness, or repressed trauma that returns in various forms of psychological disorder or violence (hence Islamic terrorism). One intactivist described sex without foreskin as “like viewing a Renoir color-blind.” This is a particularly interesting claim given that most intactivists have never experienced sex with foreskin, although some have attempted to “restore” their foreskins through arduous skin-tugging routines.

Anti-circumcision activism has its more respectable side as well. There are academic books, scholarly articles, and other interventions by ethicists and medical practioners that make the case against the practice. They argue that the foreskin is a unique piece of tissue, full of sensitive nerve endings, that serves various important functions for the penis, including lubricating and protecting the glans, and responding to sexual touch. They point out the dubious validity and argumentative flaws of studies that claim that circumcision confers hygienic benefits or protects against STDs (including a controversial 2014 CDC report, which endorsed circumcision). They link the history of the routinization and medicalization of circumcision in America to Victorian prejudices surrounding masturbation and sexuality, a subject I’ll return to later in this article. They underline the dangers of complications arising from circumcision — rare, but when they occur, potentially serious. Even when newborns experience genuine medical problems like overly tight foreskin (phimosis), these anti-circumcision experts insist that doctors are too quick to jump to circumcision instead of exploring non-surgical options. (In circumcision-happy America, they note, doctors often misdiagnose as phimosis what is actually the normal childhood state of the foreskin, which loosens as the boy’s body matures.) Finally, they argue that the medically unnecessary circumcision of infants and young children, whether practiced in a secular or religious context, has no place in a modern society that values consent, individual rights, and bodily integrity.

The situation is also quite different in the UK and Europe, where male circumcision is generally understood as a minority religious practice, and almost unheard of outside of Jewish or Muslim contexts. (I live in London, and my friends are always shocked when I tell them that most of my fellow American males are circumcised.) Given that few Europeans have heard of the medical benefits that Americans attribute to the procedure, opposition to circumcision, or at least skepticism of it, is more mainstream – especially in our era of self-righteous secularism, where everything associated with religion, and particularly Islam, has come under scrutiny. (Richard Dawkins once tweeted, “If circumcision has any justification AT ALL, it should be medical only. Parents’ religion is the worst of all reasons –– pure child abuse.”)

In 2011, a judge in Cologne, Germany ruled that circumcision violates “the right of the child to bodily integrity and self-determination.” In the kind of grand historical irony that German civil servants may be uniquely incapable of appreciating, the judge based his reasoning on the very post-WWII laws that were intended to protect Jews from the horrors of Nazi medical experiments. The Cologne decision generated a firestorm of controversy — Angela Merkel declaring she didn’t want Germany to be the “only place in Europe where Jews and Muslims couldn’t practice their rituals” — and was eventually overturned by an act of the German Parliament. The controversy inspired a recent special exhibit at the Jewish Museum of Berlin on circumcision, which displayed various ritual objects, works of art, and films related to the practice in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian contexts. The carefully curated exhibit appeared as proof that it was possible to think about circumcision with an open mind and without rush to judgment.

Yet my discussion with the exhibit’s curator revealed a darker side. In her many years at the museum, she told me, this was the first time she felt threatened by her work on an exhibit. Some intactivists — Germans included — thought that the museum’s attempt at a neutral portrayal of the issue was tantamount to endorsing it, or complicit in its perpetuation, and circulated her personal information on intactivist web forums. They found the exhibit’s cheeky title, “Snip It! Stances towards ritual circumcision,” accompanied by an image of a banana with the tip of the peel cut off, thoroughly un-funny. There was also, the curator told me, a certain, easily identifiable style of writing which appeared in some of the emails she received and the exhibit’s guestbook entries; an angry, repetitive recitation of the harms and moral wrongs of circumcision, with no reflection on the actual material displayed and the complexity of the issues it raised.

Even in the more “rational” literature, European or American, that criticizes circumcision, there is something peculiar. Google the name of any of the authors of these “saner” anti-circumcision texts, and you will invariably find that they’ve written a vast amount on the topic. Their Twitter, Facebook, and Academia.edu profiles are often dedicated to the cause; their whole lives seem to circulate around it. In short, there’s a certain “I’ve seen the light” attitude apparent in even the most thoughtful and respectful anti-circumcision activists that necessitates pause. What is it about this procedure, which is a mere afterthought for most men who have undergone it, that generates so much passion in others? Are intactivists simply right, and the rest of us have yet to wake up to this profound human rights abuse — or is there something more going on?

![]()

One of the things that’s intriguing about the effects of circumcision is that they are inherently impossible to quantify. To what degree does circumcision reduce (or enhance) a man’s capacity for sexual pleasure? Does the pain that a baby boy experiences during circumcision leave a lasting psychological trauma? These are questions that touch on two of the most deeply personal, idiosyncratic, subjective phenomena involved in being human: memory and sexuality. No study can answer these questions satisfactorily, because how a person experiences his sexuality, and whether he suffers from a traumatic memory, depend not only on the external things that happen to him, but on the particular way he generates meaning out of them.

Consider the sexual question. As we know, male circumcision leaves most of the penis intact. While we can quantify the number of nerve endings in the foreskin (about 20,000), and, to a limited extent, measure the variance in penile skin sensitivity in cut and uncut men, anyone who’s ever had a wet dream knows that sexual enjoyment is about more than the physiological capacity to appreciate friction against the genitals. Even the experience of physical sensation itself is too closely linked to an individual’s unique and largely unconscious thoughts and fantasies to be properly isolated and objectified. Try masturbating while thinking of cornflakes, and then try again while watching your favorite porn, using exactly the same hand motions. I guarantee the sensitivity of your genitals will change — though in which direction I cannot predict. (Incidentally, John Harvey Kellogg, the inventor of cornflakes, promoted both the cereal and circumcision for the libido-diminishing effects he thought they conferred.) We know that both circumcised and uncircumcised men are perfectly capable of having sex and achieving an orgasm. Beyond that, it is impossible to definitively determine where the (un)circumcised body ends and the fantasmatic mind begins. Men circumcised as adults generally don’t complain about it, which would suggest that the sexual effects are at least not hugely deleterious. Obviously, the problem is much more difficult to study for those circumcised at birth. The medical studies that have attempted to resolve this via comparative analysis are unsurprisingly inconsistent, some finding vast differences in reported sexual pleasure between circumcised and uncircumcised men, others none at all.

What if, despite these limitations, we had somehow proven that infant circumcision is neither particularly medically helpful, nor particularly dangerous or harmful? If doctors concluded that the procedure is probably unpleasant for the child, but otherwise, medically neutral — like piercing a baby’s ears? How then might we decide on its ethical permissibility?

One paper that tries to answer this question, Joseph Mazor’s “On the Case for the Permissibility of Male Circumcision,” published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, is particularly interesting for the way its rigorous application of analytical thought falls into a temporal paradox. Working on the presumption that infant circumcision is minimally dangerous, Mazor constructs the hypothetical case of Orthodox Jewish parents who want to circumcise their newborn son. He argues they are ethically justified in doing so, because they are acting in their child’s “best interests,” including primarily his ability to identify with and feel a sense of belonging to his surrounding religious community. He compares the issue to the case of a child born with non-medically threatening cleft lip. We would readily consider parents to be acting in their child’s best interests were they to elect to have their child’s cleft lip surgically repaired; though medically unnecessary, and physically painful, it would spare the child much social alienation. When dealing with a boy born into an observant Jewish family, we should understand circumcision in the same way.

Yet, there is a problem: If the parents don’t circumcise their boy, it is reasonably possible that the boy would choose to remain uncircumcised his entire life. How then can we claim that the parents are acting in their son’s best interests by circumcising him at birth? This is where fantasy, masquerading as reason and probability, begins. Mazor thinks that if this hypothetical uncircumcised Jewish boy chooses to remain uncircumcised as an adult, it would be because he is too afraid of the pain and complications associated with the procedure, which increase in adulthood. Assuming that the boy fully identifies with the Jewish community and its laws, Mazor argues that he would likely wish that his parents had circumcised him when he was a baby, so that he would have been spared the difficulties of undergoing it as an adult. Mazor thus concludes that orthodox Jewish parents who circumcise their sons are acting in their son’s best interests, even if their sons would not elect to undergo circumcision as adults, because they are acting on behalf of the knowledge of what their sons will have wanted, given what they are to become.

I borrow the wording of this last phrase not from Mazor, but from Jacques Lacan, who writes that the process of psychoanalysis involves a change in the analysand’s relationship to the “future anterior”: “what I will have been, given what I am in the process of becoming.”

Circumcision is concerned with this strange temporality, and that helps to explain what might be so troubling about it, and why it is so resistant to rational calculus. The procedure involves the physical imprinting of the wishes of an “Other” – one’s parents and their religion/culture, or, for secular Americans, the medical establishment – onto the most “private” part of the self. It suggests that what we are to become is marked in advance by this Other, or, in Mazor’s take, what we will want is shaped by what the Other wants of us. When undergone in infancy, it concerns a period of time we don’t remember, a period when we were absolutely vulnerable and dependent on others. It is disturbing to think of this state of total defenselessness, of a person I cannot remember being, but who I am told is an earlier me. What was done to me in this mysterious period of my life? Why should I have to bear its traces?

To think about circumcision is to think about a part of the self – physical and temporal – that is utterly, disturbingly foreign. It is a foundational mystery: the obscurity of our past and the uncertain impact that others have made on us. Whereas, ordinarily, we can disregard these problems, fashioning ourselves as autonomous and self-actualizing individuals, circumcision puts this anxiety-provoking mystery in brutal relief. What is more foreign and mysterious than the exigencies of my desire? What is more disturbing than the fact that my sexuality is not wholly mine? Mazor tries to domesticate these questions with logic, but, like intactivists, his reasoning only draws our attention to more fundamental unknowns.

Not unlike love and sex, circumcision is a potent receptacle of fear and fantasy precisely because it concerns something so impossible to know, something on that invisible, porous border between the self and the other. Certainty is always a bit paranoiac, and intactivists are nothing if not certain. The excessive passion of intactivists, that extra bit of zeal which makes even their most scholarly arguments seem polemical, derives not from the things that they know about circumcision, but from the things that cannot be known about it.

We live in a world that worships expertise and defends viciously against the threat of the unknown. We are constantly barraged with, and actively seek out, the advice of experts telling us how to perfect every single facet of our lives, from raising our children, to getting a good night’s sleep, to fulfilling our sexual desires, whatever they may be. Yet we are as clueless as ever about what really drives us, why we so often neglect our “best interests” or pursue things that clearly oppose them. This is particularly the case when it comes to the enigma of sex, and sexual “dysfunction.” It is always easier to have a scapegoat for one’s (sexual) problems than to face them in their terrifying obscurity. Is it surprising that, for some, circumcision would become such a scapegoat?

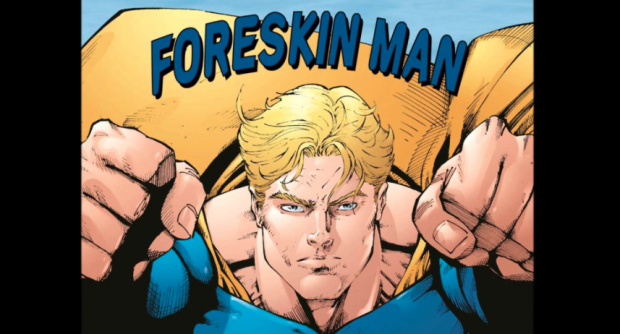

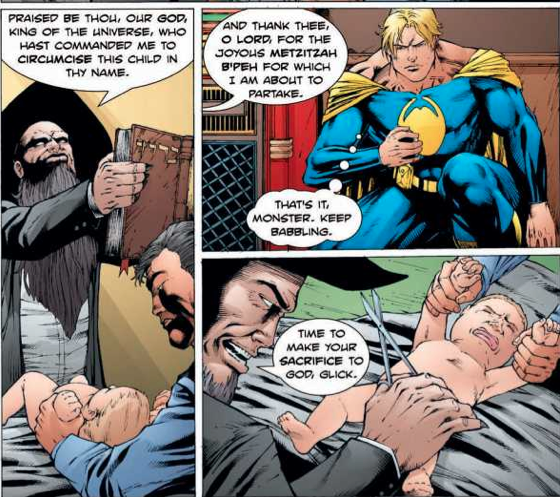

Conspiracy theories thrive in the spaces where uncertainty is greatest. While more “enlightened” intactivists strenuously defend against charges of anti-Semitism or Islamophobia, the more unhinged gleefully revive the “Jewish question” (“…this [pro-circumcision video] makes me wonder if the final solution was a good idea,” writes a YouTube commenter), or draw on Jewish stereotypes to make their case (one intactivist comic book depicts a helpless baby screaming in terror as the bloodthirsty, hook-nosed “Monster Mohel” announces, “Time to make your sacrifice to God!” — until the blond-hair-and-blue-eyed superhero “Foreskin Man” comes to the rescue). Of course we should consider the arguments against circumcision, when they are not simply racist. Indeed, some intactivists are Jewish. But if we want to know why people can become so emotionally invested in the topic — and the larger social issues that their investment points to — rather than simply whether circumcision is right or wrong, then we should look closely at these moments of conspiratorial excess.

In this respect, it is fruitful to compare our contemporary situation with an earlier moment in the history of circumcision.

![]()

In 1865, when modern medicine was roaring to life and the previously rogue discipline of surgery was finally gaining legitimacy, Nathaniel Heckford, a little-known surgeon working in London’s East End, published a paper entitled “Circumcision as a Remedial Measure in certain cases of epilepsy, chorea, &c.” At that time, the “vice” of masturbation was widely suspected to cause epilepsy and other treatment-resistant disorders. (“Chorea” was a similar diagnosis to epilepsy, involving bizarre and involuntary bodily movements.) Heckford writes about an eight-year-old boy, “of fair complexion, blue eyes, light hair, and delicate appearance,” who suffered severe “spasmodic movements … he was unable to feed himself or walk without help, and his speech was also much affected.” After an unsuccessful treatment consisting of “bark and arsenic,” the doctor re-examined him:

Immediately, the boy’s spasms reduced. “Eight months afterwards,” Heckford writes, “there had been no return of chorea, his health had greatly improved, and he had been completely cured of his former bad habit. His mental condition also progressed to a corresponding degree; instead of being dull and spiritless, he had become sharp, intelligent, and boisterous.” Heckford’s paper details four other cases where circumcision appeared to heal his young patients’ fits and improve their overall constitution with varying degrees of success.

Five years later, a much more famous surgeon, the American doctor Lewis Sayre, published a strikingly similar paper. In the opening case study, “a most beautiful little boy of five years of age, but exceedingly white and delicate in appearance,” was “unable to walk without assistance or stand erect.” Sayre first tried a standard treatment for paralysis, applying electric currents to the affected limbs. While passing the electrodes over his body, the boy’s nurse suddenly exclaimed, “Oh doctor! Be very careful — don’t touch his pee pee—it’s very sore.” The doctor was shocked to discover the boy’s penis in a state of “extreme erection”:

Sayre was so confident that the “irritation” caused by the tight foreskin was the source of the boy’s paralysis, that he immediately arranged to circumcise the boy in front of an audience of medical students. As with Heckford’s case, there was a miraculous recovery. And again like Heckford, Sayre tried the procedure on other boys suffering similar symptoms. His paper details six very successful cases. Sayre, for his part, theorized that boys who suffer from paralysis, “nervousness and fainting fits,” may have appeared to be guilty of masturbating, but in all likelihood the source of the problem was a purely somatic “genital irritation” caused by constrictive foreskin, not moral degradation.

There is no evidence that Sayre was ever acquainted with the work of Heckford. If we are to rely on Sayre’s account, he seems to have independently stumbled upon the idea to circumcise. Sayre eventually became famous on both sides of the Atlantic, primarily for his pioneering work in orthopaedics. He was a tireless medical organizer, reformer, and sanitation advocate, and held a number of prestigious professional positions, including the presidency of the American Medical Association. Though circumcision was not the cause of his celebrity, he publicized his views on the procedure widely, and given his prestige, they were taken seriously. We owe the medical routinization of circumcision in America in no small degree to Sayre’s work.

How did these two doctors independently come up with the same idea, so far removed from our current medical knowledge?

We have known at least since Foucault that the Victorians were paranoid about, and therefore in the habit of proliferating, sex. Improper, excessive sexuality lurked around every corner, associated with unruly behavior and florid physical ailments, such as the endlessly enigmatic “hysteria.” Childhood masturbation was especially worrying, a focal point of medical concern. In Heckford’s and Sayre’s articles, the fear of childhood sexuality is palpable and laced with excitement. Their patients suffer from “extreme erection,” “nocturnal emissions,” and recurrent orgasms. The symptoms are also feminized: The boys are almost always figured as passive, “delicate,” “clumsy,” “unable to walk without assistance,” coddled by nurses.

In keeping with the ideas of some sociologists, Lacan claimed that the turn of the 19th century marked the decline of the figure of the “master.” Capitalist modernity was initiating a major shift in the social structure, deposing traditional figures of authority and institutional anchors like the church. The symptoms of this change were visible in the new theater of medicine. The ever-shifting, recalcitrant symptoms of the hysteric presented a seductive challenge to the fin de siècle doctor. Hysterics, almost always female, undermined the doctor’s certainty, constantly toying with his authority and drawing attention to the shaky foundations of his discipline. Like the wider society, doctors displaced the anxiety of their own impotence, generated in them by the hysterics (and indirectly by the larger social shifts), onto the idea that they must curb excessive sexuality in all its manifold forms. However, as men of science, they formulated the targets of their assault in the reigning vocabulary of medical expertise: “genital irritation,” “reflex neurosis,” and so on.

Circumcision, it seems, enabled Sayre and Heckford to reassert masculine mastery against dangerous eruptions of feminine sexuality. The cut removed the offending superfluous flesh, and cleaned out the contaminating “secretions” found inside, imprinting stable patriarchal order onto the little phallus – and apparently, it often worked.

They did not get carried away, however. Heckford admitted that the procedure wasn’t fully curative for all his patients, and Sayre recommended a conservative approach to cases of adherent foreskin, if possible tearing the foreskin from the glans rather than removing it entirely, “which as a matter of taste and ornament is sometimes desirable.” Yet once the linkages between the foreskin, improper (feminized) sexuality, and illness were out there, it was only a matter of time before the full web of associations was spun. The influential Californian doctor Charles Remondino, who called Sayre “the Columbus of the prepuce,” showed just how far these associations could go in his popular 1891 book History of Circumcision:

Sound familiar? Intactivists often cite this medical history as testament to the pseudo-scientific origins of routine infant circumcision. While most of the quack cures of the Victorian era have now vanished, circumcision, they argue, is a traumatic hangover of our repressive past. Yet, with just a few adjustments in style, Remondino’s feverish treatise sounds identical to a contemporary intactivist Twitter page. Nearly all of the problems he blames on the presence of the foreskin are the same as those that some intactivists attribute to the loss of it. The point is not that they are wrong — of course neither circumcised nor uncircumcised penises can explain moral weakness, lunacy, or terrorism. Rather, by taking arguments about circumcision to the extreme, both speak the “truth,” in a certain sense, of the dominant ideology of the time; the libidinally charged fantasies that lie just beneath the seemingly rational justifications for or against the procedure.

![]()

In traditionally authoritarian societies, we must sacrifice our private pleasures for the sake of the public good. Freud thought that these repressive demands of civilization made people ill, and that the hysterics were bearing witness to it. His solution was to talk to them. Other men of his time, however, tried to reverse the failures of traditional sexual prohibitions by inventing new ways of enforcing them. Victorian paranoia around sexuality, which was symptomatic of larger social upheavals including the loss of the traditional master, gave rise to the medical expert, who promised to reinstall rule and order with precise surgical interventions. Figures like Remondino make visible the fantasmatic underside of this enterprise.

Yet if yesterday’s experts thought they could circumcise away the excesses of eros, today’s experts have taken a different approach. Rather than facing a prohibition on sexual pleasure, today we are subject to unceasing imperatives to partake in it, what the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek has called late capitalism’s “injunction to enjoy.” We should sleep with our partners every night to keep the oxytocin flowing, masturbate regularly to fight depression, and for a healthy prostate, we should try anal beads. No longer overtly punitive, today’s authorities, in the new guise of scientific experts and their pop culture spokespeople, induce us to maximize our enjoyment — for our own as well as society’s good. For those public heath authorities that promote it, circumcision is not about preventing masturbation but about preventing AIDS and urinary tract infections, optimizing our sexual health. Intactivists, of course, are fully on board with this “sex positive” logic; they merely disagree with those doctors who think circumcision is a part of it.

Of course, this loosening of sexual mores is welcome. But, as many have already warned us, it is a mistake to view our era’s sexual permissiveness as unproblematically liberatory. Our “freedom” to enjoy, as Žižek frequently reminds us, has become an imperative issued by the super-ego, a command that seems to emanate from some powerful and cruel internal force, making us constantly question whether we are enjoying enough, and whether someone else might be enjoying more. We accept the pro-pleasure ethos of our times only to find ourselves faced with a relentless pressure that no amount of sex, consumption, or social media activity seems to discharge.

Drawing on psychoanalytic ideas, the literary critic Eric Santner writes that the experience of anxiety today is “not of absence and loss but of over proximity, loss of distance to some obscene and malevolent presence.” While it seems as though contemporary intactivists are complaining about the former, portraying the absent foreskin as the source of all misery, their violent rage towards those who practice circumcision expresses something else — a sense of intrusion, of the dissolution of boundaries, of the violation of body and mind. Yes, something has been taken away, there is a prelapsarian wish for the return of the lost object. However, the intactivists’ articulation of lack always points towards an overbearing presence, an evil entity that violates the defenseless child and leaves an irreversible, protean trauma.

A Dear Abby column published on March 21st exemplifies this combination of lack and violation, along with the traumatic temporality foregrounded by circumcision. “Cut Short in California” writes, “When I was in grade school, I was sexually assaulted by an older classmate, but I feel much more violated from [my] circumcision because it took a part of me that I can never get back. I am filled with hate and anger toward my parents, even though I know it is unfair to them because they believed they were making the right choice at the time.”

When talking with Joseph Mazor, who argued in favor of the ethics of circumcision, he asked me whether I thought that the trauma expressed by intactivists was “real.” It’s a difficult question to answer. I do not doubt that they truly feel the pain, anger, and sense of urgency that they express to others. However, I also think that stances on circumcision, be they personal or political, cannot be examined in a vacuum. Opposition to circumcision today is symptomatic of the profound anxiety brought on by the particular configuration of authority experienced under late capitalism. To quote a skeptical urologist, intactivists “are fighting much larger demons.” The real question is whether any of us, inactivist or not, wants to face them.