“But then the mind is easily gripped, meticulously tricked, even more easily flipped. There’s a word, cocina, which means ‘sty,’ in my language, but means kitchen in another.”

The first thing is this: even when we don’t know it, we pray that our bodies will carry us on. Keep us longer, we silently ask. Here, together, we pray.

We forget the measure of time, most of the time. We can’t conceptualize the medley of incantations our bodies bestow upon themselves. The chorus of our contracting muscles, the hymns of our traveling blood. Persistent requests made of limb and skin. The pettiness of it all. We forget to give thanks to an obedient cervix, praise an unrebellious kidney.

You used to be particularly interested in this, the multitude of ways your body could betray you. Us. But you weren’t interested in the ways in which it betrayed me alone, in the end. You used to ask me so many questions about it, as though I was some kind of learned master of your body. But the language in which it lived was mostly foreign to me. I couldn’t interpret you. I couldn’t help you at all. I refused when you asked me to hit your pudgy chest, hard. You told me your wife did it (daring me) but you knew I wasn’t anything like her. You liked that I was gentler and milder.

Maybe I did help you, though. For a while. Even for a long while. But then I couldn’t anymore, and you left. Absence, exactly like death. Enacting your own worst fear. A brilliant trick, it was. Only long after you left did my malign prefrontal cortex begin to fathom life again. Bits of you always at the edges of things. Phantoms blooming and unwanted.

![]()

You fucked me so few times it hurts. The first time our bodies touched beyond the merely acceptable (for a married man and his best friend, that is), I had come to visit you. Unchartered realms. Lands of your grandparents, which you’d reclaimed so well (you always had a knack for claiming things). You wanted to show me things, in that cobbled city, that other playground of your dreams (here’s grandpa, you said in a graveyard; here you are, where you belong, you said that night in the coffin of your bed). Must have been just west of somewhere and north of elsewhere. Somewhere she wasn’t, somewhere you snatched time away from her to write your histories (about bodies fighting other bodies). To begin rewriting our history (bodies finding other bodies). We lit candles for dissidents and martyrs, read memories etched in stones, epitaphs to young dead poets (the kind of immortality you craved). Prayed to find one another in that mid-summer dusk. I think we both knew that it had to be then or never.

For years (a thousand two hundred and ninety-five days) our bodies had waltzed about each other frugally. Until at last a dissipating edge of night found our minds cloaked in fog, our faces washed pale moonlight. Collapsing together on the creaky couch in that fin-de-siecle living room. Mingling, smoothing, opening—bewildering pageant of things unspoken. But there were rules, which I made up that night. Arbitrary and brazen, unfair to our bodies: lips weren’t allowed to touch lips, no question of your body inside mine. But still we came, humping each other’s legs, like dogs.

But rules, like promises, are meant to be broken. And so they broke. Big news. I’m getting a divorce, my phone (that holy talisman) announced on landing. Sans serif, sans gravity, I stepped off the plane that had flown me away from you (day one thousand two hundred and ninety-six, it was). I love you, I love you, I love you. A coup of disambiguation.

![]()

Yesterday I went back to our place, unchanged in the thousand days since you left me. Let’s go to that place where the sangria is cheap and makes our blood red with wanting, where the patatas bravas make us forgetful and brave, we never said to each other. The place where the stallion-like barman makes me so lustful (he used to, even with you near). Where I can watch his guileful hands, strong arms swinging over cold marble to pour liquid like ardor into our glasses. That alcohol we used to take so deliberately, so greedily. While we poured ourselves into each other. Bound by a tacit understanding that we needed it, needed it to cloud our minds and mist our eyes and rain the melancholy of our unrequitedness over us. To embolden us to chase that frugal dance, the chemistry reacting loose and wanton and deceptive over us.

You used to watch me watching him, perversely. Taking in his aquiline nose, chiseled Spartan features. Short, thick ponytail (helicoid chanterelle) at the base of his neck. I’m going to write a story about the rugged fields of Greece that his ancestors came from, I told you, yes, the fields where I boldly imagined the bodies of his grandparents must have met, planting the seeds of him. Which he’s brought all the way here, imagine, I said, desperate to imagine something other than the fallow fields of our bodies, so near and unsworn. But you had stopped listening. Instead you watched me watch his broad shoulders, which widened like an inverse tree-trunk, bursting with sap. Inviting release. And the tattoos crawling down his arms, wide Thracian columns, ink flowing like Poseidon’s waves. It reminded me of centuries of branded flesh, fields of flesh invisibly branded by flesh.

I wanted him, his body taking mine, but with your brain implanted in that body (one day I’m sure they’ll be able to do that, too, we said of the impossible). It never ceases to amaze me, what a mass of 1,300 grams can hold. Encased in their prison of bone and flesh, grams holding cities and tongues and history, moments of love, and molecules and ancestors and fading light, darkness too, and rivers and bodies and colors, and those lost, like you.

– but this is where I can tell that I’m losing steam, that my expression is becoming sloppy and sentimental and solipsistic, that my insights are dissipating into a babbling stream –

Watching our barman, I wonder what he remembers. Does he remember the days we used to come in the laden grey of winter, my frostbitten hair to your heavy wet hat? Your wedding band to my naked un-possessed fingers? Does he remember the way you used to sigh and look at me, proclaiming life is strange! like a refrain, a mantra that could rescue us from your predicament? Implying that your brilliance, your strangeness, your selfishness, was something to be rewarded, something that could only be rewarded by my understanding (yes, that is what you believed; and why can’t she be more like you, you said)? Does he remember the way we used to weave hours into the fabric of our past together, so entirely contented, so unreservedly devoid of all other wants? Entranced by each other’s thoughts (all breathless words and nipping eyes) untouching bodies (all restrained hands and volcanic blood). The relentless ticking of clocks oblivious to us, until last call, he’d announce.

On those nights the whole world stood encapsulated in your sidelong glance, in the vibrato of your words, too close to my cheekbones (those very ones you said you loved). In my head leaning too near your shoulder, hair coyly flicked in your direction, and your hands brushing surfaces, slightly squeezing edges, of me. The studied intent of innocence, feigned to perfection.

![]()

But then the mind is easily gripped, meticulously tricked, even more easily flipped. There’s a word, cocina, which means “sty,” in my language, but means kitchen in another. A long-faced horse-woman, talking to a too-clean-faced IMF man, is explaining this (still here at our place; still without you). You can tell that they met on the Internet, that last sentinel (stupid and headstrong) of their clinging hopes. Shiny and slight as a whistle (nothing to want in a man), IMF says something about Pravda and Sputnik, and only I can tell that she, the horse-woman, hasn’t any clue. My Greek and I exchange knowing eyes, look at these poor fuckers, they say, we can only hope they’ll go home to take some comfort in each other.

You knew everything about Pravda, about the Sputnik. About fanciful flights into the truth of our love, which you convinced me of so well. You made me believe in everything, then made yourself as distant as aliens in other universes. And who are you? That’s how you ended your first email to me, do you remember? Pleasantries. About yourself, your history and your History—both were gifted to you, then claimed and made by you (isn’t it marvelous, you asked?)—in cascading paragraphs, words flowing as only you could make them do. And then, the afterthought. who are you?

I think that’s when I fell in love with you. Assaulted by that unthinkable combination of nine letters. We’d met just a few days earlier, crowded together in a bright room. The paintings of a small-time artist surrounding us (poor bastard’s soul, bathetically bared). A cacophony of friends and cocktails around us. The Historian, they said you were, the man to watch. Bit of a hypochondriac. Wife a bit of a bitch. They said and said. But it was that question, as essential as it was useless, that got me. Remarkably, you always made me feel just like that. A postscript morphing into a prelude.

I think about that monosyllabled enquiry too often. My reminder that there was some substance of me, waiting to be discovered. To be found by you. This hollow meaninglessness of finding people (someone). Seeing them try to find each other, seeing them shop for each other like they do for handbags to wear on their arms, or for books to fill their hours with, in virtual spaces. What do they actually want, I keep asking.

![]()

And now, the day suddenly threatens to cease. An indigo veil has fallen over the city’s glass and metal and stone. IMF is still talking about himself, the horse-woman is still nodding like she’s after a lump of sugar. And here I sit, obedient chewing cow. The stupid machine of my body performing its automatic life. Made dumb by my biology, my memories. And I’m still so terrified of the life I’m missing. The life not being lived with you (your monophobia, an invasive species).

The trees want to whisper something but they can’t. They just shake themselves minutely, outside my window (it’s mine, because I’m the one who sees all these things through it. Just like I used to see things through you. So many things, you showed me, told me).

Why are they always claiming things for themselves, the trees ask, fruitlessly bemoaning this human disease of possession.

![]()

After we’d make love in my studio (once we’d returned from the cobbled city, to days dark and short and strange, like you), I would linger between sleep and wakefulness, hiding from the glare of neighbors’ lamps and televisions, light traveling across thin air. Watching you in the window, as you sat at the kitchen counter. Drinking the whiskey you had bought, which I refused to keep for you. Writing your History, unwriting our history. It helped with the pain, you said (at least you didn’t think you had your mother’s fibromyalgia, which I didn’t think actually existed). There was always the pain.

Usually when I couldn’t sleep, I’d find way to entice you back into bed, to demonstrate what pleasure our bodies could produce. You always obliged. You shook and shuddered in such a feminine way that I laughed the first time. You laughed with me, and I was glad. Almost histrionic, I told my friend months later, in a moment of darkness. I’d never controlled a body like that before (no measured grunting, no paced withholding), and this compensated for the inadequacy of your body. This must be how men feel, controlling our bodies like this, I told Lena. I felt like I’d one-upped Leonard, no, Mr. Cohen, I don’t have to be a man to know how good that feels, how sweet. Because you, you just surrendered to me like an obedient, helpless piece of meat. Released from your body by my body, your imagined pain absent for a moment. You never did understand why I used to be a vegetarian.

Other times, I would ask you about your work, though I knew it all, knew exactly what you’d say. All you need to know is that history betrays us, just like our bodies do, you’d say. How right you were. I should’ve understood it sooner, but I refused and tried instead to make you see the beauty of your unbeautiful body (the fact that it contained everything). For the pain you tried acupuncture, reflexology, everything. But only the whiskey helped. And the fucking. My hands, my mouth, my cunt—the best medicine on the good days. I was always so eager to dispense it, like some illicit morphine drip, and you could hardly believe it, you said. She hadn’t taught you that women too wanted to use their bodies like this. You thanked me for this (you were always thanking me for everything; excessive gratitude is the height of narcissism, I learned later from my therapist).

Once, I tried to tell you about how I can become so easily overwhelmed by this physical sense of repugnance for other bodies. How sometimes, contemplating a strange man’s limbs, I can imagine his animal weight on top of me, and my inevitable pleasure, cascading almost too easily, without repulsion. But then at odd times, in the metro, the supermarket, the airport (always in airports, those perfect microcosms of human longing), when a stranger’s heat accosts me, I’m repulsed to all degrees. And then the thought of having to commune with a strange body, to learn its intricacies, its patterns, its colors and curves and callouses, depresses me deeply. Heaves me into a sad mania. I could have nightmares about the glint of hairs, shameless patches of skin with their unbearable hints of underneath, hanging chins like sad pelicans. Disgusting, you said.

![]()

The way time flows when I do this, when I write about you. Like unlived time, it can go on boundlessly, obliviously. Like sleep, unaware of its limits. I don’t want anything, and nothing wants anything of me. It’s the anatomy of emptiness, a solo for ink and fingers. It speaks to me because I speak from it, pull things from it. Things that no one else has aligned (no, not even you), in quite the same way. It’s the uniqueness of me: what you taught me about myself. That I have something to say, something to make them listen. That I’m worthy of what, I don’t know (maybe of nothing more than you). You showed me that I matter, and that can’t be destroyed, not even by your realizing otherwise.

Thinking about it, I find that words only flow out of my body so apoplectically when my skin touches paper as I used to touch your skin. Apparently nothing else mattered as much as your body communing with my body. A Faustian bargain, that union of our bodies. Because if we hadn’t crossed that inalienable line, you wouldn’t have feigned this death, and we’d still be somewhere, sometimes. Talking, laughing, longing.

Only the deepest intimacy can lead to nothingness. But somehow that’s normal. The whole world says so. Our friends claim they understand these imagined deaths people enact between one another. I call it the great paradox of our time (mine and yours). Time exhausted and extinguished, spent and mummified. Don’t get me wrong. I can handle it when it has to be (unlike you). But feigning nothingness is blasphemous. I’d have expected something better from someone as plagued by superstition as you.

Which brings me back to your fear of your body. Strange, to live in this constant fear. I tried to convince you so many times that it was a needless fear, a paradox—you betraying yourself. But you never agreed that you’re just your body. Because look at all those bits of you, released in the world. Disembodied, uncontained. In the hard-won syllables and sentences populating your books, evidence of your mind interpreting the world for an audience. Your pleasure at the thought of strange bodies ingurgitating your words (your diligent striving for immortality). I always marveled at your sense of authority. How you could convey everything so easily, when underneath you were always afraid. Afraid of everything underneath.

![]()

Fetid childish infatuation. Your terrific fear of monotony and death. These are my memories of you, at your worst. At best, I tell myself that your desertion amounts to a compliment, a notice that I’m so potent, so bursting with explosive things that you had to enact a death between us. Now bodies disturb me increasingly often, send me into that old state of malaise. Parroting the hateful indifference that sometimes used to descend abruptly and rest heavily on me after an orgasm (like sleep for most men, but not for you). A more active disgust.

You promised forever. I promised myself. Vice. And versa. And then you left. But your body didn’t leave mine, didn’t speak to me. Instead your fingers fed your thoughts to some keyboard, which swallowed and spit them at me. When you left, you wished me all happiness. I wish you all happiness, you wrote, I wish you all success, as if mocking me to find these things outside your body. I tried to find you in that ensuing volcano of silence. To no avail. Maybe it was just that kind of death—the true kind, always inexplicable—that you needed to perform, to stop dreading it. Maybe the old witches of Prague did something to you when I wasn’t looking (your nose did always remind me of them).

And then you married her, the radiation oncologist. I read this somewhere—your words, your thanks to her, staring me down from a page inside your latest tome. Enthralled that you still spoke to me, despite the best of your intentions. Maybe it was the guilt that got you in the end, I sometimes think. Remembering how you reproached me for dancing on the grave of your marriage once, in the aftermath of a particularly memorable fuck. But then I think that it can’t be, because there she is, your first wife being given thanks, too. Undead to you.

So I was just the raft that carried you from one to the next (postscript and prelude), like Lana said. She said I warned you didn’t I, that he’s just using your body as a crutch for his body, to heal from his brokenness with her, that one day after everything, when you’ll be gratefully ready to settle into gratified and grateful bodies existing in nearness, you’ll remind him of that crutch, he’ll see only that acrid medicine he swallowed to save himself. And that’s not an aftertaste anyone wants to live with, not a side-effect to be remembered.

I hope he dies of a cancer she can’t cure, I told Lana.

*

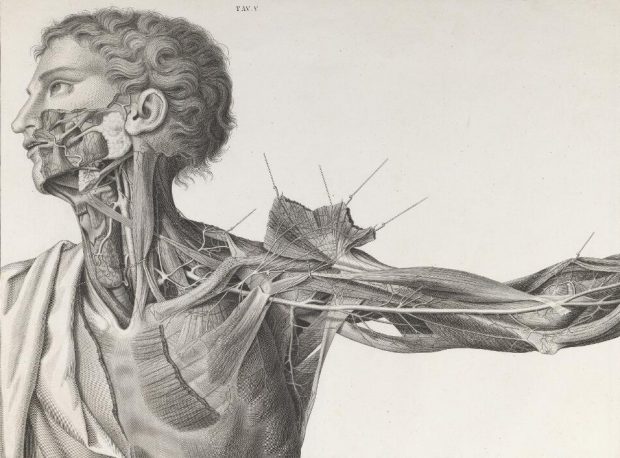

Image by Antionio Scarpa, 1804