“Now I had never been crucified, but I had been in fights, so I knew something about the amount of blood a body could produce.”

I always hated going to Sunday School. I guess I never saw the point in coloring pictures of the crucified Jesus. Anyway the teachers never liked my drawings. They always accused me of making them too bloody and awful-looking. Now I had never been crucified, but I had been in fights, so I knew something about the amount of blood a body could produce. In one fight, Chip Edwards had smashed my face repeatedly onto the end of a sliding board. There was a lot of blood after that – way more than I ever tried to color onto Jesus with a red crayon. But my teachers, especially Mrs. Merckel – they just wouldn’t listen to reason. The crucifixion, Mrs. Merckel tried to explain to me, had actually been a happy event. Jesus, she told me, pressing some yellow and gold crayons into my hands, had probably smiled a little up there on the cross.

That I knew was total bullshit.

The stuff my parents got to talk about in adult Sunday School seemed way more interesting. They discussed real things, like what to make of a god who occasionally let good people die in plane crashes or just put a bullet into their heads, as my best friend’s father had done the previous summer at his brand-new house on Lake Summit. But my parents wouldn’t take me to their class. They said it would make the other adults uncomfortable.

Eventually I just started skipping Sunday School. After the early service, I’d go to the hall where the church offices were (they were always closed on Sundays), lock myself into a bathroom stall, and read a book. I was big into Poe back then: “The Black Cat,” “The Pit and the Pendulum,” “The Masque of the Red Death.” I think I read all of Poe’s stories by the time I was ten. H. P. Lovecraft, too. This truancy ended when a frightening old deacon, who for some reason was always picking me out to help with the offering during the early service, caught me reading in the bathroom and ushered me back to class. Mrs. Merckel took one glance at the book in my hands, marched me out into the hallway, and spanked me. Now I knew the principal at my elementary school had permission to spank, and I had even seen the wooden paddle with the holes in it. But a spanking at church?

One Sunday, Mrs. Merckel had us all make pairs of Play-Doh animals for a table-sized ark that her late husband, she said, had labored to finish for us before dying of lung cancer. When I showed Mrs. Merckel my alligators, however, she took them away and crushed them back into the lump of green Play-Doh in the center of the table. She tried to explain that Noah hadn’t allowed any alligators onto the ark because they would have swallowed all the good animals up. Besides, she said, alligators could swim. She said she had seen one herself swimming at high tide off Hilton Head Island. I asked Mrs. Merckel whether Noah had allowed snakes onto the ark. Heavens, no, Mrs. Merckel said. She told me that the devil himself had probably scooped the snakes and all the other bad creatures up in a great, long net, like the ones you use for crabbing.

When Mrs. Merckel said that, I decided I was finished with Sunday School. I liked snakes and had been planning to become a snake handler ever since the day I had seen an old man extract venom from a cobra’s fangs at the serpentarium in Miami. It was the single most amazing thing I’d ever seen in my life. The venom, the snake handler had told us, holding up the vial, was worth its weight in gold and could cure all sorts of diseases. So if God hadn’t allowed cobras onto the ark, I told myself, then I didn’t want a damn thing to do with Mrs. Merckel or with God.

The next Sunday, after the early service, I decided to hide out in the basketball gym in the Family Life Center across the street. I wasn’t sure the gym would be open, but if it was, I figured I could practice foul shots or something instead of building more animals for Mrs. Merckel’s stupid ark or breaking open sand dollars, finding the doves, and talking about miracles.

The Family Life Center was connected to the church by an underground tunnel that ran from the social hall beneath the sanctuary. The door to the tunnel was unlocked, as was the door to the center itself, which besides the gym housed the soup kitchen, the food pantry, and classrooms for youth groups – the same ones where I’d heard that Billy the youth minister had caught Jennifer White giving Tyler Thornton a blow-job while everyone was supposed to be eating dinner at Sugar and Spice.

The doors to the gym were open, and though it was pitch black inside, I found the bank of light switches along the wall. The overhead lamps took a long time to come on and made a buzzing sound I had never noticed before. Each one was like a hornet’s nest. When I picked up a basketball and bounced it, it took three seconds for the echo to die.

After the alligator incident, I had told Mrs. Merckel that I didn’t believe in God. I received three spankings for that remark: one from Mrs. Merckel, a second one from my mother with a medium-sized wooden spoon, and then the real one from my father with a belt. If the point of those spankings was to make me believe, they had failed, so I am not sure how to account for what happened next. Maybe the sermon that morning during the early service–something I never paid any attention to, preferring instead to circle all the instances of the word “ass” in the Old Testament–had been about the temptation of Christ. Anyway, I carried a basketball to center court, bowed my head, and began praying –really praying–for the first time in my life. It was a simple request: I wanted was a sign. Something to convince me that all this God stuff wasn’t a bunch of crap. A basket or two from center-court, I said to God, would do the trick.

You can imagine my surprise, then, when I made a shot. Nothing but net, either. A perfect swish. I can still hear the sound, clear as day. Then I took a second shot and made it, too. It wasn’t as pretty as the first – it banked in – but still. I wasn’t exactly the star player on the First Presbyterian 11-and-12-year-old youth team, and I had just made two shots in a row from center court, including a swish. The swish I could dismiss as luck, but the second one was harder to discount.

Now, I knew it wasn’t inconceivable for a kid to make two shots from center court. It wasn’t, I mean, incontrovertible proof of the existence of God. Once, for my birthday, my father had taken me to the Charlotte Coliseum to watch the Harlem Globetrotters play some scrawny and confused-looking team from the Soviet Union. There was this one Harlem Globetrotter who had made five shots in a row from the catwalk that led to the jumbotron. Furthermore, he’d made the shots backwards. What I mean is, he’d bounced the balls off the court and back up through the basket and off the glass so another Globetrotter could dunk them home.

I stood there at center court for a long time while I considered taking another shot. But I couldn’t bring myself to do it.

I don’t think I was worried that God was messing with me. Maybe he was, just a little, on that first shot. But the second shot? Surely God had better things to do on his day of rest than to fuck with the faith of a twelve-year old boy.

Maybe I was afraid that God wasn’t screwing with me–that there really and truly was no God–and that I simply didn’t want to face the implications of air-balling a shot after two had gone right in.

Now I find myself wondering whether that was it, either.

I mean, think about it for just a second.

How many basketball shots would you have to make from center court before you were absolutely and completely convinced of the existence of God?

*

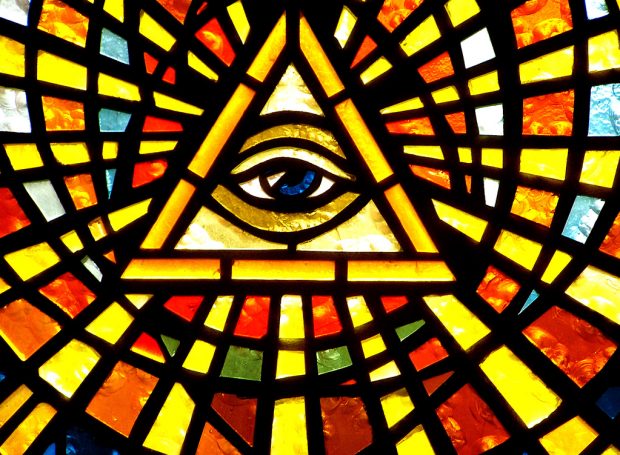

Image by Liz West